Books

I KonMari'd My 1,127-Book Library — And Let Go Of A Lot More Than Books

I definitely arrived late to the Marie Kondo party. By the time I got around to reading The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, Kondo’s book had already made waves with clutter-lovers and minimalists alike, the buzz had died down, the book had become a pop culture reference in the 2016 reboot of Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life, which is how it ended up on my radar in the first place. The Christmas after a bereaved Emily Gilmore discarded her entire joyless wardrobe, my mother — knowing I love organizing almost as much as I love Gilmore Girls — gifted me Kondo’s book. Until just a few months ago, it joylessly cluttered up my shelves.

But then Kondo and her infamous KonMari cleaning method went from book to Netflix original, and suddenly she was everywhere again. Beloved, hated, willfully misunderstood: few things in recent history have highlighted just exactly how much we Westerners love hanging on to our crap more than Marie Kondo and her controversially joyful drawer organizers. Not one the be left out, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up found itself at the top of my TBR pile.

I loved it. Not only was I completely won over by Kondo herself — I too, relished any opportunity to help tidy my elementary school classrooms — but her method actually worked. My closets and kitchen transformed. Getting dressed in the morning actually felt luxurious, now that my clothing was thoughtfully folded and visibly color-coordinated. Cooking and cleaning up after meals ceased to be the source of contention it had become between my partner and I, now that everything had a rightful place and I was no longer spending valuable time digging through seven whisks in order to find the herb stripper.

Beloved, hated, willfully misunderstood: few things in recent history have highlighted just exactly how much we Westerners love hanging on to our crap more than Marie Kondo...

I was a Kondo convert. Except for one, pretty glaring exception: books.

Books seem to be where a lot of people part ways with Marie Kondo, usually due to accidental or deliberate misunderstanding of the KonMari method. Part of this is due to the “30 books myth," wherein people take significant umbrage with the idea that Kondo recommends owning no more than 30 books. (In fact, she doesn’t.) In her book Kondo does mention that the ideal number of books for her own household is 30 — but in no way is she suggesting that 30 books is the ideal number for every household. Kondo doesn’t demand that book-lovers wrench themselves away from their favorite reads, nor does she — as some critics have suggested — “hate books." (She gives long-neglected books little love taps to “wake them up” before sorting through them, for goodness sakes.) Rather, as with every other category of item she tidies, her focus is on having respect for what you own, gratitude for what you discard, and possession of only what is of value to you.

Books seem to be where a lot of people part ways with Marie Kondo, usually due to accidental or deliberate misunderstanding of the KonMari method.

"Ask yourself, by having these books, will it be beneficial to your life going forward?" Kondo says, in the fourth episode of her Netflix series. "Books are the reflection of our thoughts and values. So by tidying books, it will show you what kind of information is important to you at this moment."

I own a lot of books. As I sat, watching that fourth episode of Tidying Up with Marie Kondo, I owned exactly 1,127. (I counted them before KonMari-ing them.) I don’t know how many books the average American household owns — or the average American bibliophile, for that matter — but 1,127 seemed a tad excessive.

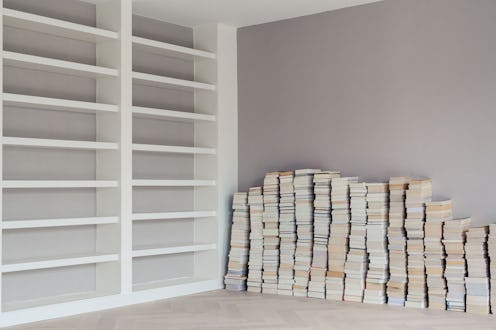

In owning so many books, I’d sort of stopped seeing them for the excess that they were: By constantly being everywhere, individually they had become invisible. There were books in every room, stacked on every surface. Books piled on dining room chairs and lining the kitchen counters. Books filled dresser drawers and closet shelves. The top of each bookshelf housed more rows of books, stacked on more rows of books. (They fell over A LOT.) There were piles of books on the floor stacked so high that they blocked the photographs and artwork on my wall. Books from every undergraduate and graduate course I took, and some from courses I’d never taken; guidebooks for every country I’d ever traveled to, or wanted to travel to, or thought I should want to travel to; books I’d read and loved, read and not loved, never read, might never read.

The thought of piling them all in one place, touching them one-by-one, and discarding what would certainly amount to hundreds, was painfully overwhelming. Plus, I loved them.

But that’s where the KonMari method forced me to get real with myself. Because, if I’m being honest, I didn’t love each and every one of my 1,127 books. What I loved, rather, was owning them. I loved what I imagined guests thought of me upon seeing all of the books. In a way that somehow expressed both shameful pretension and painful insecurity, I loved what I imagined piles of 1,127 books said about me: I’m intelligent; I’m well-read; I can converse eloquently on a multitude of subjects (but, like, seriously don’t ask me to); I’ve been to Morocco; I’m a feminist; I’ve watched a lot of Gilmore Girls; I can grow my own vegetables; I went through that random astrology phase when I turned 29; maybe one day I’ll give birth in a tub of water in my living room; maybe one day I’ll change the world.

But that’s where the KonMari method forced me to get real with myself. Because, if I’m being honest, I didn’t love each and every one of my 1,127 books.

But these books said practically nothing about my own particular thoughts and values as a 30-year-old woman. Instead, they allowed me to cling to the various young women I had tried to be over the last decade-plus of my life. They allowed me to ignore the fact that I had not, at 30-years-old, become the exact woman that the girl who bought all those books thought she would become.

Suddenly, the only thing my excessive book ownership sparked was the realization that maybe I was being kind of a bookwormy asshole.

I knew there was no way I was going to be able to whittle my collection down to anything close to 30 books (even though, again, that’s not what Kondo suggested in the first place.) But I started with the humble goal of discarding 30 percent. (That’s 339 books, for anyone who’s keeping track.) And it wasn’t easy. When it really came down to it, I wasn’t letting go of books — I was letting go of what I thought those books would mean to me in my life, and didn’t; letting go of the woman I'd imagined would have use for those books, a woman who I did not become.

Suddenly, the only thing my excessive book ownership sparked was the realization that maybe I was being kind of a bookwormy asshole.

I kept Harry Potter. I discarded Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. I kept three different editions of Pride and Prejudice and discarded 11 books about politics in the Middle East. I let go of nearly every single book I purchased while pursuing a degree that, admittedly, I’m not really using. I held on to The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. I let go of Walden. I kept a lot of essay collections about imperfect mothering and discarded a lot of books about how to be a better mother. I no longer have any Proust, F. Scott Fitzgerald, or Flannery O’Connor. I have a concerning number of books about cults. If I ever go to Argentina or South Korea, I’ll be doing it without the guide books. If you ever come over to my house for dinner, you're going to have to suffer awkward conversation with someone who is learning not to hide behind piles of books.

It hurt to say goodbye to those books. It hurt even more to say goodbye to the person I once thought would be reading them. But in doing so, I created the space necessary to honor not only who I am in this moment, but whoever it is I’m going to be — and what I'm going to read — in the future.