News

How Trump's Focus On Working Class Men Hurts Working Class Women Like My Mom

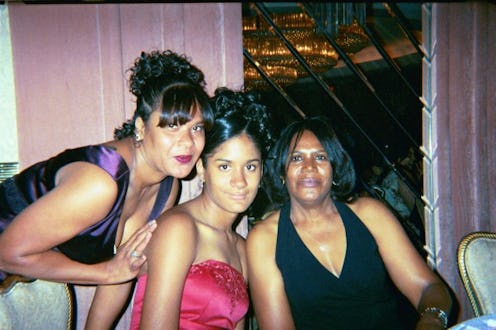

I grew up weaving in and out of clothing racks at Loehmann’s on Broadway in the Bronx, waiting for my mom to clock out or give me the house keys if she was stuck working late. I’d pass the time by hiding among Donna Karan cashmere tops on markdown, trying on Stuart Weitzman heels on clearance in the shoe section, and wrapping those beige slip-on sock things around my hands like mittens. My mom, with her beautifully highlighted hair, wore plum wine lipstick, black loafers, and a velvet blazer that she paid for with her first-ever check from working in retail.

My mom has lived in New York her entire life, and for the last 20 years (since her late teens), she has worked in small shops and big department stores all over the city. She counts herself among the one in 10 Americans, 16 million retail workers total, who work as cashiers and sales associates in the retail industry across the United States.

When I was younger, my mom would warn me that I needed to do better than her, not getting stuck in what she’d call a “dead end job” — a job that paid the bills, but that wasn’t for ambitious, educated women like me who could “make it.” Before working at Loehmann’s in the late 1990s, she also worked at another brick-and-mortar, Annie Sez, which wound up closing when I was in middle school. During this time, my other family members pitched in more to help my mom with her unpredictable work schedule and late hours. My grandpa started taking me to school more, and I ate more meals at my grandma’s house. Because I was still young, I didn’t fully understand how this impacted my mom and our economic status, but I knew that my day-to-day life now involved more people in our family, and not so many babysitter visits. I also knew that fewer hours meant more financial stress for my family, even if I selfishly hoped this would mean more time for her to take me to the park and play.

There seemed to be little stability for my single, working mom who knew retail like the back of her hand, but whose busy schedule prevented her from pursuing other activities that would further her career. Last-minute schedule changes and late nights working inventory became costly babysitting bills, and hardly incentivized going back to school to get a more advanced degree.

As my mom gets older, the uncertainty of a life in retail is even more concerning. My mom isn’t comfortable using the technology that is becoming standard in most jobs, and she has few resources to help her with training. Most companies would just rather hire a younger person who knows how to use an iPad instinctively, or avoid paying additional healthcare or child care expenses that women over 25 often require, so people like my mom are getting left behind.

If this story sounds familiar, it’s because you’ve heard it before. But you’ve probably heard about young male factory workers in Detroit or coal miners in Virginia — not middle-aged Latina saleswomen from the Bronx.

Every election cycle — and especially in 2016 — it is common to hear a defense of "blue collar" and "working class" jobs (who can forget Joe The Plumber?), but Donald Trump takes a particularly heavy-handed approach to the issue. During Trump's campaign, he mentioned coal miners 294 times. “Coal is coming,” he claimed on a campaign stop in Ohio; he told another crowd in Washington DC, “Employing a lot of people, and we are putting the coal miners back to work just like I promised — just like I promised." Everywhere Trump went, when he discussed saving American jobs or putting folks back to work, he would highlight the coal mining industry as one of those workforces worth preserving.

And yet, despite putting his name on several retail-related products, such as wine, suits, and steak, it’s hard to locate a speech where Trump mentions the plight of retail workers in any of his descriptions of “American workers” — and there’s a very conspicuous reason for that. Trump’s talk about “blue-collar” and “hard-working” “working class” folks isn’t about appealing to people like my mom — it’s about winning over the white, hetero, cis-male voter. Which he did.

The retail workforce looks like the emerging America that Trump and his base fear, which is probably why they are underrepresented in conversations about "the working class" and "American jobs."

Perhaps in one of his many illogical hiccups, Trump is unable to see that “working class jobs” and retail careers, like the one my mom has, are synonymous. And, no matter what you want to label them, they’re both under threat. No matter if the entire coal industry – a typically white, cis-male space — was revived overnight, the number of jobs saved would be totally eclipsed several times over by the number of retail jobs we stand to lose in the next 10 years due to increased automation and the changing nature of the retail experience. And the loss of those retail jobs won’t just impact the women who work those jobs, but their families, and the communities that rely on them — An estimated 60 percent of department store workers are women, and over 40 percent of women in low-wage jobs provide half or more of their household income.

Trump’s omission of retail jobs from the conversation on working class jobs isn’t anything new. The retail workforce looks like the emerging America that Trump and his base fear, which is probably why they are underrepresented in conversations about “the working class” and “American jobs. This is also why their particular needs — my mother’s particular needs — aren’t taken seriously.

The challenges women in retail face are undeniably magnified by race, religion, and gender expression in intersecting ways that white men in industrial jobs don’t regularly experience. Working class women are routinely discriminated against based on their gender, their race, and ethnicity on top of their gender, penalized for being LGBTQ, getting pregnant, their immigration status, requesting time off for child care, getting older, and everything in between. In the retail world, this means that only the young and childless stand a chance of surviving.

Nearly half of retail workers don’t find out their schedules until a week in advance.

Just as with coal, there’s no easy answer to how to ensure the retail industry stays afloat, or how to ensure that women in retail are well-paid and employed into their old age. However, addressing the core issues of pay disparities, child care and maternity leave, and concerns around erratic work and pay schedules would certainly make a difference.

Erratic scheduling is actually a really good place to start. As the National Partnership for Women and Families points out, nearly half of retail workers don’t find out their schedules until a week in advance, making it difficult for mothers to find childcare, or for caregivers — who disproportionately tend to be women — to find reliable, quality support for their elderly or disabled loved ones.

I remember staying with multiple babysitters as a kid. There was Mamita across the street from PS 7, and sometimes I’d stay with an aunt or a friend of my mom’s if she couldn’t afford to pay for an extra day of babysitting. When my mom was off, she was exhausted and didn’t want to do much besides catch up on her shows, get her hair done, and rest — a reminder that women need time off from all the work they do, not just the work they get paid for.

Even as the Trump administration turns a blind eye to these issues, some politicians are taking notice. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (CT-03), joined by 72 co-sponsors, recently reintroduced The Schedules That Work Act, a bill that would protect low-wage employees from erratic work schedules. It would require employers to give folks two weeks advance notice of any schedule changes, which would help working class women better budget time and money for their families.

I’m sure she thought aspects of her industry were unfair and wished she could take a stand, but that can be a difficult thing to do when you’re overworked, raising kids, and already come from a marginalized community.

Another solution — though one that is often a struggle to achieve — is to unionize, which has worked before in industries like teaching, policing, and manufacturing. “If retail workers were able to organize strong unions across the country, there’s no reason retail jobs couldn’t be good jobs like manufacturing jobs,” Amy Traub, Associate Director for Policy and Research at public policy organization Demos, tells Bustle.

One of the many issues with unionizing is that companies are averse to change, especially when that change involves paying workers more money or providing them with more resources. “[Many big box] companies are still built on the outdated, sexist model that their typical employee on the sales floor is a housewife who’s earning a little bit of money but the household budget doesn’t fundamentally rely on her contribution,” explains Traub. “She has a husband who’s the real breadwinner, so she doesn’t really need to be paid a family-supporting wage. Walmart popularized that model across the country, but now almost every big retailer pays that way because that’s what the market will bear. Yet that’s not who retail workers are.”

My mother never talked about unionizing — I’m sure she thought aspects of her industry were unfair and wished she could take a stand, but that can be a difficult thing to do when you’re overworked, raising kids, and already come from a marginalized community. As for me, the first time I really understood organized labor’s power was in seventh grade, when a classmate of mine delivered a passionate presentation about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, noting how important women like Frances Perkins — who would go on to be labor secretary under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt — were to moving labor reforms forward.

For kids like me, who were fed and clothed because of the retail industry and spent our childhoods watching our parents go off to jobs that lacked security, let alone advancement, this is about as extensive an education on labor as we got. But of course, we did hear about the industrial revolution, the tough guys who built cars, and how factory jobs created the US economy. The work that we value in this country is not separate from the gender and race we value as well, which is why women like my mother often seem invisible, especially in the workforce.

We could have had more time together to play and probably most importantly, to rest.

But I saw, and I see, my mom every day — her value is wholly visible to me. She taught me to work hard, to fight for myself, and to take care of the people around me. She provided for me as a kid, working unfair schedules for way too little money, and making everything I have now possible. But as we both get older, I am realizing that things could have been different for us. We could have had more time together to play and, probably most importantly, to rest. While I can’t go back and change history, it is important to me that to ensure that we, as a society, have a more nuanced understanding of who the working class really are, as well as a common agreement on how to support them. For too long, we’ve dismissed the dignity of working in retail. From the small business owners to the cashiers to the sales associates who help people feel good about themselves (which my mom did for me every day), the women of the retail industry are moving our economy forward just as much, if not more than factory workers — and they deserve to be regarded just as highly as their coal-mining counterparts.

Jess Torres works in communications in Washington, D.C, and all views expressed here are her own.