Books

This YA Novel Is A Heart-Wrenching Exploration Of The Grief Of Losing A Parent

"My grief is tremendous, but my love is bigger," or so wrote author Cheryl Strayed about her mother, who died when she was in college. In Girl In Pieces author Kathleen Glasgow's new novel, How To Make Friends With The Dark, a teenage girl reckons with the a tremendous grief after the death of her mother — but more importantly, she learns to embrace a new reality where love can be found in unexpected places.

How To Make Friends With The Dark follows 16-year-old Tiger Tolliver, a high schooler who would probably be described (and describe herself) as deeply uncool. Her over-protective mother barely makes enough money for them to get by, and Tiger is desperately uncomfortable in her ill-fitting, thrifted clothes that do little to mask her changing body. Despite it all, they're deeply close. They're each other's only family — which makes it all the more brutal when Tiger's mother dies unexpectedly.

While this is a novel about grief and moving forward after an unimaginable loss, it is also a a novel about what makes a family. As Tiger charts a new path forward, she realizes the necessity of her "chosen family" — her best friend Cake, her grief support group, a recently discovered half-sister, and her child services case worker. Maybe she isn't quite as alone as she feels.

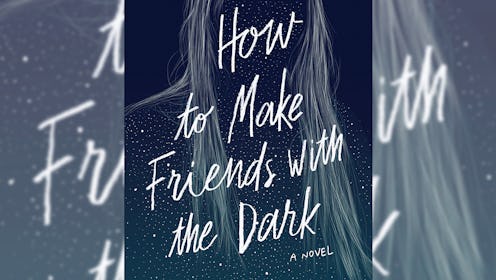

Bustle has an exclusive first look at the stunning cover, plus an excerpt which you can read below. Kathleen Glasgow's How To Make Friends With The Dark is available for pre-order and will be published on April 9, 2019.

How To Make Friends With The Dark by Kathleen Glasgow, $19, Amazon

Excerpt

I FIND THE BILLS BY ACCIDENT, stuffed underneath a pile of underwear in the dresser my mother and I share. Instead of clean socks, my hands come away with a thick stack of envelopes marked Urgent, Last Notice, Contact Immediately.

My heart thuds. We don’t have a lot, we never have, but we’ve made do with what my mom makes as the county Bookmobile lady and from helping out at Bonita’s daycare. Come summer, we’ve got the Jellymobile, but that’s another story.

You don’t hide things in a drawer unless you’re worried.

Mom’s been on the couch since yesterday morning, cocooned in a black and red wool blanket, sleeping off a headache.

“Mom,” I say, loudly. “Mommy.”

No answer. I check the crooked clock on the wall. Forty minutes until zero period.

We’re what my mom likes to call “a well-oiled, good-looking, and good-smelling machine.” But I need the other half of my machine to beep and whir at me, and to do all that other stuff moms are supposed to do. If I don’t have her, I don’t have anything. It’s not like with my friend Cake, who has two parents and an uncle living with her. If my mom is sick, or down, I’m shit out of luck for help and companionship.

And rides to school.

But I need the other half of my machine to beep and whir at me, and to do all that other stuff moms are supposed to do. If I don’t have her, I don’t have anything.

“Mom!” I scream as loud as I can, practically ripping my throat in the process. I shove the bills back beneath the stack of underwear and head to the front room.

The scream worked. She’s sitting up, the wool blanket crumpled on the floor.

“Good morning to you, too,” she mumbles thickly.

Her short hair is matted on one side and spiky on the other. She looks around, like she recognizes nothing, like she’s an alien suddenly dropped into our strange, earthly atmosphere.

She blinks once, twice, three times, then says, “Tiger, baby, get me some coffee, will you?”

“There’s no coffee.” I use my best accusatory voice. I have to be a little mean. I mean, come on. It looks like we’re in dire straits here, plus, a couple of other things, like Kai, are currently burning a hole in my brain. I need Mom-things to be happening.

“There’s nothing,” I say. “Well, peanut butter. You can have a big fat hot cup of steaming peanut butter.”

My mom smiles, which kills me, because I can’t resist it, and everything I thought I might say about the stack of unpaid bills kind of flies out the window. Things will be fixed now. Things will be okay, like always.

We can beep and whir again.

Mom gets up and walks to the red coffeemaker. Coffee is my mother’s drug. That and cigarettes, no matter how much Bonita and Cake and I tell her it’s disgusting and deadly. When I was little, I used to wake up at the crack of dawn, ready to play with her, just her, before she’d drag me to the daycare, and I always had to wait until she had her first cup of coffee and her first cigarette. It was agony waiting for that stupid machine to glug out a cup while my hands itched with Legos or pick-up sticks.

She heaves a great sigh. “Shit,” she says. “Baby! I better get my ass in gear, huh?” She’s standing at the sink, trying to turn on the faucet, but nothing is coming out. “The water’s still crappy? I was hoping that was just a bad dream.” She nods to the faucet.

“Pacheco isn’t returning my calls.” Mr. Pacheco is our landlord and not a very nice one.

She murmurs, “I guess I’ll have to deal with that today, too.” I’m silent. Is she talking about the bills? Maybe I should—

Mom holds out her arms. “Come here, baby. Here. Come to me.”

I run so fast I almost slip on the threadbare wool rug on the floor and I go flying against her, my face landing just under her collarbone. Her lips graze the top of my head.

Mom trembles. Her shirt’s damp, like she’s been sweating. She must need a cigarette. “I’m sorry,” she whispers into my hair. “I don’t know what happened. What a headache. Bonita leaving, the daycare closing. I just . . . it was a lot all at once and I guess I stressed. Did you even have any dinner last night?”

I had a pack of lime Jell-O, and my stomach is screaming for food, but I don’t tell her this. I just keep nuzzling her.

My mother pulls away and laughs. “Grace,” she says. Hearing my real name makes me cringe. “Gracie, that pajama top doesn’t quite fit you anymore, baby doll.”

I pull defensively at the hem of the T-shirt and cross my arms over my chest.

My mom sighs. I know what’s coming, so I prepare my I’m bored face.

“Tiger,” she says firmly. “You’re a beautiful girl. I was just teasing, which I shouldn’t have done. You should never hide you. You’re growing into something wondrous. Don’t be ashamed.”

Wondrous. She and Bonita are crazy for the affirmation talk.

Cake likes to say their mission in life is to Build a Better Girl Than They Were. “You know,” she said once, “their moms probably put them on diets of cottage cheese before prom and told them to keep their legs closed around boys.”

Cake likes to say their mission in life is to Build a Better Girl Than They Were.

I roll my eyes and groan. "You have to tell me those things,” I answer. “You’re my mom. It’s in your job description.”

Her face softens and I feel guilty. Once I overheard her say to Bonita, “I try to tell Tiger all the things I never got to hear, you know?”

And I always want to know, what didn’t she get to hear? Because she’s tight-lipped about her early, non-Mom, kid-like days. Her parents died when she was in college, and she doesn’t like to talk about them.

My mother rummages around in the cabinets and somehow, somewhere, finds a lone can of Coke, even though I scoured the cabinets last night for spare eats. She takes a long, grateful sip and then wipes her mouth. She fishes in her purse for a cigarette.

“Go get dressed, Tiger. I’ll drop you at school and then I’ve got a lot of things to do. Today is going to be one hell of a day, I promise. Food, Pacheco, the works. I’ll make up for being out of it, okay?”

“Okay.”

Mom heads out in the backyard to smoke and I hit my bedroom, where I frantically try to find something suitable in my closet of mostly unsuitable clothing. My mother thinks finding clothes in boxes on the side of the road is creative and fun and interesting and environmentally conscious (“One person’s trash is another person’s treasure!”) and not actually a by-product of our thin finances, but sometimes I wish I went to school dressed like any other girl, in leggings and a tee, maybe, with cute strappy sandals to highlight pink polished toenails. Instead, I mostly look like a creature time forgot, dressed in old clothes that look like, well, old clothes.

I drag on a skirt and a faded T-shirt, and jam a ball cap on my head, because the water in the shower is starting to look suspicious, too, so a shower is out of the question. I brush my teeth like a demon in the bathroom and splash water on my face.

Then, like I always do, I allow myself a minimum of three seconds to wonder: Who the hell is that? Where did she come from?

Because the dark and wavy hair is nothing like my mother’s short, light mop. My freckles look like scattered dirt next to her creamy, blemish-free face.

So much of me is from The Person Who Shall Not Be Named. So much of me is unknown.

But here I am, and for now I need to get my mother in gear, get to school, make it through zero period and the little five- day-a-week shit-show I like to call “The Horror of Lupe Hidalgo,” which, if I survive, leads to Bio, and to Kai Henderson, the very thought of whom makes my heart start to pound like a stupid, lovesick thing, and who is one of the things I need to talk to my mother about.

So much of me is from The Person Who Shall Not Be Named. So much of me is unknown.

In the car, she fiddles with the radio dial. My empty stomach is blaring like a five-alarm fire, so I scrape some Life Savers from the bottom of my backpack. Maybe lint and dust have some calories and I can last until lunch.

I’m sucking away when my phone buzzes. Cake.

She up?

Yes! In car.

Thank God! You tell her yet?

I glance over at Mom. She’s muttering, trying to tune the radio in our ancient Honda, a car partially held together by duct tape and hope.

She looks tired. Maybe her head still hurts, after all. Maybe it’s the bill thing. Maybe I should get a job, help out. I could bag groceries at the Stop N Shop. Or bus tables at Cucaracha.

Not yet, I type.

Just do it. Rip off the Band-Aid, Tiger. Then you can flee the vehicle and not have to deal with her until tonight.

I don’t answer. This is going to be a complicated issue, the Kai thing.

My mother is a little overprotective. She is not going to be happy about me going to the Eugene Field Memorial Days Dance with Kai Henderson. Not because she doesn’t like him, because she does. She’s known him since he was a scrappy kid at Bonita’s with bruised knees and a yen for butter cookies. She just doesn’t like me . . . well, not being with her.

“Aha!” She grins. “Here’s a good one.”

She turns up the volume. Another song from years ago, nothing new, nothing I ever get to pick. She wrinkles her nose at the songs Cake and I play in our band, Broken Cradle, calling it a lot of experimental noise. It’s possible I’m the reason it sounds “experimental,” since I mostly bang away on the drums with no idea what I’m doing. I’m only there to back up Cake, who’s basically a musical prodigy. And Kai, who looks dreamy and sweet, plucking his bass, his brow furrowed, like one of my books might say.

Maybe it’s the fact that I suddenly feel like my mother is always drowning me out that I blurt, “I’m going to Memorial Days with Kai Henderson.”

As soon as I say it, I both regret it and relish it. I mean, what is she going to do? I’m sixteen. I can go to a dance like everybody else for once.

She turns down the music. “What?” Her voice is slow. “Since when? When did this . . . happen?”

I take a deep breath. “A couple weeks ago. He asked me. I’m going. It’s going to be fun. Cake’s going, too. Everybody’s going.”

“Wait,” she says, again. “Kai? As in Kai Kai? Our boy with his head permanently buried in a medical textbook?”

I sigh. “Yes.”

Silence. My heart drops. I knew it. I can almost count the seconds, so I do: ten . . . nine . . . eight . . .

“I don’t know, Tiger. This is so sudden and we haven’t talked about it. I mean, there’s the drinking thing, probably an after- party—”

I interrupt her. “I don’t drink, I don’t party, I don’t smoke. No one has ever felt my boobs except that one gross doctor, and I just want to go to a dance and dance like everybody else. For once.”

“Do you . . . is this . . . is he your boyfriend now? Has that been going on?”

I can feel her eyes on my face. A blush creeps up my neck. “No.”

I mean, not yet. Maybe. Someday. Like, after the dance, maybe. Isn’t that how things work? You kind of slide into something? All I know is books and movies and watching other kids at Eugene Field and remembering how it was with Cake and the boy from Sierra Vista. I mean, what do I ever do without my mom, anyway? Nothing. I go to school, sometimes I watch the skaters at The Pit, I come home, I read, I . . .

I sit in our small life. Watching everybody else. A bug in a jar, pacing.

I mean, not yet. Maybe. Someday. Like, after the dance, maybe. Isn’t that how things work? You kind of slide into something?

In the distance, kids flood the parking lot and front lawn of Eugene Field High School. If I can just hang on until we get there, I’ll have seven hours Mom-free. My stomach makes an unseemly rumble from hunger. I feel faint and dejected.

Why does just one stupid normal thing have to be so hard?

“It’s only a dance,” I whisper. Tears form behind my eyes. My nose prickles. I’m starting to buckle, just like I always buckle. I buckled when she acted like gymnastics was too expensive, even though it was just a few classes at the dinky community center on half-worn mats. I buckled when Cake wanted me to take dance with her, when I had a chance to join after-school chess, all of it. The only thing I ever had was skateboarding, and that was four years ago, and then she took it away.

“I’m going to the dance with Kai Henderson,” I say, my voice suddenly steely. “And you can’t really stop me. And it would be wrong if you did.”

My mom pulls into the lot, narrowly avoiding Mae-Lynn Carpenter, weighted down with her giant backpack. She glares at us before moving on. I don’t think I’ve ever seen Mae-Lynn smile.

“Grace,” my mother says. “We should talk about this later. It’s a big thing. It’s not as small a thing as you think.” She puts her hand on my arm.

“No,” I say, and then it happens. Tears, springing from my eyes. “It’s exactly as small as I think. It’s streamers and spiked punch and cheesy music and a party after. Something kids have done since the beginning of time, but never me. Not until now.”

“Tiger, please,” she says, but I’m already out the door, hoisting my bag over my shoulder, keeping my head down so no one can see me cry.

As soon as I take my seat in zero period, the texting starts, my phone buzzing insistently inside my backpack, starting a little war with the chaos happening in my unfed stomach. Those Life Savers weren’t very lifesaving, after all.

“It’s exactly as small as I think. It’s streamers and spiked punch and cheesy music and a party after. Something kids have done since the beginning of time, but never me. Not until now.”

The noise alerts Lupe Hidalgo, much like the smell of tiny, frightened humans alerts sleeping giants in fairy tales.

Lupe Hidalgo sighs. Lupe Hidalgo stabs the point of her sharp, sharp pencil into the table. Lupe Hidalgo’s legs are jiggling, the soles of her boots pumping against the black-and-white-tiled floor of zero p.

She glances at me, coldly, and then down at my backpack. She frowns.

There’s some quick eye-to-eye action between me and the three other kids at our homeroom table. Tina Carillo looks at me; I swipe my eyes to Rodrigo; Rodrigo stretches his hands behind his head and rolls his eyes to Kelsey Cameron, who doesn’t look at anyone, because she’s too busy looking at herself in her phone and angling her head for a selfie.

Lupe tap-tap-taps the pencil. She bends her head to the right. She bends her head to the left. Her sleek black ponytail bounces against her back.

This is the signal that she’s about to let loose on someone. The only time Lupe can focus is on the softball field. It’s why she’s headed to the U of A next fall on a full scholarship. The ability to throw a ball so fast and hard it’s rumored her catcher, Mercy Quintero, ices her hands for hours after a game. The ability to nail a line drive into the soft stomach of an unsuspecting girl from Flagstaff.

Lupe Hidalgo is so good at softball it’s like she’s the only one on the team. I mean, I know I’ve seen other girls traipsing along the halls of Eugene Field with high ponytails and striped knee socks on game day, their black and gray team shirts open and flowing, the fetching white fox mascot slinking along the game day T-shirt underneath, curling among the letters of Zorros, but for the love of God, I have no idea who they are.

Lupe Hidalgo is an eclipse. She slides over everything like a glamorous shadow, and even though you know it’s going to hurt, you look anyway.

And I accidentally do. In an instant, my heart is in my shoes. My stupid, faded white Vans that I’ve markered up with stars and moons and a little facsimile of a cradle cracked in half, in honor of our band.

Lupe slides her glistening eyes up and down my body. Instinctively, I fold my arms across my chest. You never know when somebody, usually a guy, but sometimes a girl, is going to make a crack about my breasts.

You have a beautiful body, Mom always says. Stop slumping.

It’s easy enough for her to say. Her boobs are like tiny overturned teacups on her chest, delicate and refined.

I force my mother from my brain. Our fight in the car didn’t leave me as triumphant or heroic as I’d have liked. Mostly, now, I feel sick, hungry, and kind of scared. I resolve to not think of her anymore today.

On cue, my phone buzzes. It’s like my mother knows I’m trying to X-Acto knife her from my day.

I cannot believe I have sixteen million nerve-racking, day- killing things happening all at once.

Silently, I will Ms. Perez to stop bumbling around the front of the classroom and start already, but she’s remaining obstinately unaware of the hell that is about to be unleashed on me and keeps shuffling papers around her desk.

Tina Carillo murmurs, “Here we go,” and shrugs at me. Lupe finishes giving me the once-over and growls, “Girl, what the fuck you wearing today?”

My body stiffens. The source and fact of my clothing has been an obsession of Lupe’s since she rubbed mashed potatoes into my Hello Kitty tee in the third grade at Thunder Elementary. “Stupid cat,” she’d said. “Dumb shirt.”

Next to me, Rodrigo snorts and pulls out his phone. “I mean, for Christ’s sake, who do you think you are? Stevie fucking Nicks?”

Now, you might not be aware of the golden goddess of seventies music, the muse of a weird band called Fleetwood Mac, one of the strangest and most ethereal singers ever to float across a stage in six-inch heels, layers of velvet, and shimmers of lip gloss and fairy dust, but here in hot-as-hell Arizona, birthplace of our golden girl, we all know who Stevie is.

Lupe takes the hem of my unicorn-bedazzled T-shirt between her forefinger and thumb and leans close to my face. Her makeup is smooth and perfect, eyeliner spreading toward her temples like black wings.

“Girl,” she breathes. I hear the slight pop of gum far back in her mouth. “Just . . . no.”

Kids around us giggle. One girl, whose name I can never remember, but whose face always looks like she just sucked a lemon, snaps a photo of me.

Super, now I’ll be a laughingstock worldwide: #geek #weirdo #highschoolfreak #unicornloser.

My face burns, an instant heat that I know everyone can see. I’m awful at not blushing or being embarrassed, or not being able to show when I’m furious, or frustrated. Mom calls this a passion for life, but then again, my mother is the reason I’m being mocked at 7:25 a.m. in Room 29 at Eugene Field High School in Mesa Luna, Arizona.

Every day I go to school dressed like a miracle ticket hopeful from a Grateful Dead concert, and if you don’t know who that is, look it up, and you’ll see lots of confused people in tie-dyes and velvety skirts with bells at the hem trying to see a band made up largely of stoned dudes in dirty T-shirts and holey jeans who look like they haven’t washed their hair since the sixties, when they started this nonsense in the first place. My wardrobe consists of old band tees, the aforementioned hippie skirts, men’s pants, old suit jackets, and sometimes a hand-knit scarf, for “flair,” my mom says.

I’m awful at not blushing or being embarrassed, or not being able to show when I’m furious, or frustrated.

I look away from Lupe and down at my clothes. I can’t even pick my own damn clothes.

My phone vibrates. Instinctively, I kick at my bag, like that’s going to make the ringing, and my mother, stop.

Lupe looks at me and shakes her head. “Aw, your mama checking up on you again?”

She makes this sound like Mm-mn-mm-nooooo, and holds up her hand, flipping her wrist. Kelsey Cameron laughs. I glare at her, semi-betrayed. We aren’t friends—I just have Cake—but still! We share this table with the demon that is Lupe Hidalgo. That should count for something.

Sorry, Kelsey mouths. Lupe sighs and gestures in my direction. “I can’t sit next to this. What if it rubs off on me? On this?” She glides her hands down her body, like she’s a game show hostess. Lupe Hidalgo is mean and beautiful and even though she’s wearing just a white T-shirt and black jeans and those boots, she’s a shimmering, dangerous goddess.

I just don’t understand how two girls can both be teenagers and yet one girl seems so adult, and knowing, and sexy, and the other, me, is like this piece of lumpy dough.

It’s like a memo went out and only some girls got it.

I raise my eyes. Mae-Lynn Carpenter is across from me at another table, bent low over her notebook, the end of a pencil jammed sloppily in her mouth. The back of her shirt rises above her pants, revealing a downy patch of skin. Beside her, two girls are snickering at the bright white underwear peeking over the elastic waistband of Mae-Lynn’s pants.

It’s like a memo went out and only some girls got it.

Girls like me and Mae-Lynn definitely did not get that memo.

I can feel tears brimming, because Lupe’s got everyone’s attention now, everyone except Ms. Perez, who’s now writing something on the board.

If Cake was here, she’d have something snarky to say, but she isn’t, and a thousand times a day, in situations like these, I think What would Cake do? And I like to joke that I should get one of those bracelets, only it would say WWCD instead of WWJD, but Cake laughs that off. “You just need to yell more,” she says. “Mouth off. Live up to your name.”

Everyone loves Cake. Everyone admires Cake. She’s five feet ten inches worth of awesomeness, bravery, and black and purple hair coiled in perfect Princess Leia buns. She’s a bona fide rock star in the making and the sole reason I haven’t been completely relegated to Nowheresville on the Eugene Field High School Ladder of Desolation.

I look at Mae-Lynn Carpenter again. She is the last stop of the High School Ladder of Desolation. They should probably just name it after her.

Mae-Lynn is wearing a pink sweatshirt with a kitten on it. A kitten with actual fur and an embossed pearl necklace. I swallow hard. At least I’m not that low. My unicorn might be bedazzled, but at least it isn’t furry.

I adjust my T-shirt so that it’s not riding up my belly as much. Lupe tsk-tsks.

My phone buzzes again. My stomach yelps. Lupe looks down at my bag, curious. “What is so important, I wonder? Did baby girl forget her lu—”

“Lupe Hidalgo and Tiger Tolliver, are you ready to learn today or do I need to send you both down to Principal Ortiz?”

Finally. Ms. Perez’s voice booms from the front of the classroom. In an instant, you can hear the shuffle of phones being slid under tables, makeup bags being zippered, the clearing of throats. Ms. Perez, once she gets going, does not fuck around, even with only one month left in the school year.

Lupe tosses her head, her ponytail swinging. The tables in zero p are round, and she swivels to face the front of the classroom, so her back is to me. Her shoulder blades press against her T-shirt, straining like wings beneath the cloth.

Lupe Hidalgo is so beautiful it hurts to look at her, so I look away, at the clock high on the wall, and begin my countdown to Bio, and Kai Henderson.