Books

In 1936, This 'Vogue' Editor Changed The Way The World Thought About Single Women

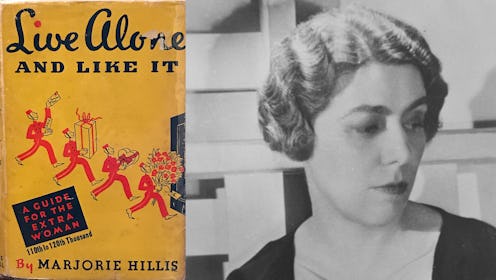

In the summer of 1936, a short, snappy, and stealthily radical self-help book for single women became a surprise bestseller. In the depths of the Great Depression, Live Alone and Like It: A Guide for the Extra Woman celebrated women’s pleasure and glorified their independence. The book offered "old maids" and "spinsters" an enviable new identity. Instead of "extra women," surplus to society’s requirements, they could reinvent themselves as "Live-Aloners," defined by what they did, not what they lacked. The book’s author, Marjorie Hillis, was a Vogue editor and the daughter of a minister, but by the time she was in her 40s, she was preaching a gospel of breakfast in bed, a well-fitted suit, and a perfectly mixed Manhattan. Her approach to single life was pragmatic, not moralistic. The odds were good that her readers would find themselves alone at some point in their lives, she wrote, “even if only now and then between husbands." When that happened, what were they going to do about it?

Unlike many books aimed at single women at the time, Live Alone was singularly uninterested in helping them find a man. (Although, to the publishers’ surprise, plenty of male readers picked up the book and helped make it a hit; President Roosevelt was snapped reading it on his summer vacation.) Despite this, men barely register in the book's philosophy. They’re useful for making up a bridge foursome or putting up a shelf, but they aren’t necessary to women’s happiness, and their presence guarantees nothing. Live Alone is coy about sex, generally recommending that a woman avoid "affairs" entirely until she’s in her 30s and knows what she wants. The chapter titled "The Pleasures of a Single Bed" is almost entirely about early nights, fancy bedclothes, and breakfast on a tray. But its tongue-in-cheek title is obviously deliberate, poking fun at the centuries-old, sexualized anxiety about what women do by themselves behind closed doors.

The odds were good that her readers would find themselves alone at some point in their lives, she wrote, “even if only now and then between husbands."

The prospect of a woman’s self-sufficient pleasure is threatening and invites disruption — just ask anyone who has tried to read a book alone at a bar. We’re used to thinking of pleasure as something decadent, selfish, and fragile; today, it's reframed as “self-care,” as though it’s only acceptable to treat ourselves kindly if it’s a kind of therapy, repairing ourselves to face the working world again. But for Marjorie Hillis, guilt-free pleasure was a declaration of intent, for a woman to live life on her terms. It was the source of the Live-Aloner’s happiness, and her power.

Her road to that philosophy was long, and unlikely. Born in Peoria, Illinois, in 1889, Marjorie Hillis moved with her family to Brooklyn at the age of 10. Her father was head of a prominent church, and her mother was a conventional Victorian wife, who believed that women could only find fulfillment in marriage and family life. When Marjorie, who considered herself "undeniably plain," took a job at Vogue magazine, it was only supposed to last until she married. But she discovered that she loved the work, so when no husband came along, she kept at it. Vogue taught her to value fashion as a source of confidence, and she reminded her readers how hard it was to make a good first impression "in run-down heels and an unbecoming hat." It also taught her that what she valued most in her life was her own independence. In 1929, the year she turned 40, the national crisis of the Wall Street Crash was overshadowed in her own life by the deaths of her parents within a year of each other. Marjorie packed up her family’s suburban home and fled back to the city, to build the life she wanted, by herself.

Marjorie Hillis worked between the major feminist "waves," in an era defined more by economic woes rather than gender politics. It was a boom era for self-help, when readers wanted and needed to hear that success was possible, and that they could triumph over the economy’s fearfully stacked odds if they greeted the world with a smile and a positive mental attitude. Live Alone and Like It was unusual in being aimed at women, but it also emphasized the importance of optimism and self-belief. When it sold more than 100,000 copies in its first three months of publication, Marjorie traveled the country preaching her message, and department stores arranged tie-in promotions for all the items — from cocktail shakers to negligées — that the Live-Aloner needed for her glamorous solo existence. Her publishers scrambled to catch up to the fact that a book they had thought of as a fun curiosity was becoming a social movement before their eyes. Its success made single women visible in the culture in a way that they’d never really been before, at least not in a way that was aspirational rather than pitiable.

Live Alone and Like It was unusual in being aimed at women, but it also emphasized the importance of optimism and self-belief.

Marjorie quickly produced a sequel, Orchids on Your Budget, a guide to frugal yet fashionable living which nevertheless remained far more aspirational than realistic. Next, Corned Beef and Caviar for the Live-Aloner, which she wrote with a Vogue colleague, offered a collection of recipes for the solo hostess. In 1939, she published both a book of poetry about single women in New York, and a guide to the city for Live-Aloners who were visiting the vast World’s Fair. Critics said her books spun a fantasy that only the richest women could achieve, yet the Live-Alone spirit had an impact beyond the women who could afford to emulate its author directly. For all of the department store promotions and energetic marketing, Hillis never suggested that you could simply buy your way to happiness: It was a question of knowing yourself and your values, and choosing accordingly.

In June 1939, just three years after Marjorie Hillis had first become a household name, newspapers reported with astonishment and glee that the nation’s spinster-in-chief was getting married after all, at the age of 49. They crowed that she had betrayed her readers, and her philosophy, by announcing her engagement to a wealthy widower in his 60s, the founder of a chain of grocery stores. Marjorie protested in vain that she had never said the single life was better than being married, only that it could, and should, be enjoyed when it came. But the jokes at her expense were too easy to make. During her marriage, as World War II raged, she retreated into the luxurious obscurity of married life.

Marjorie protested in vain that she had never said the single life was better than being married, only that it could, and should, be enjoyed when it came.

The turbulence of the Depression and the war made Americans receptive to new ways of living, including the idea that women needed to work to support themselves and their families. But after the war, there was a powerful resurgence of the idea that women’s highest purpose was childbearing and housekeeping. As 1950s dawned, Marjorie Hillis’s husband died suddenly, after just 10 years of marriage. Once again, her response to personal tragedy was to pack up and move to a solo apartment in the heart of the city, and start to write. Her 1951 book for divorcees and widows, You Can Start All Over, was tempered by her own grief, but still celebrated the independence and happiness of single life. In the crushingly conformist climate of the 1950s, however, nobody wanted to hear that there might be another way for women to be happy.

By the late 1960s, the heyday of Helen Gurley Brown’s Cosmopolitan magazine and Sex and the Single Girl, Marjorie Hillis was a refined relic. In the photograph on the back cover of her final book, 1967’s Keep Going and Like It, she looks like a glamorous dowager — albeit one with a wicked sense of humor and some stories to tell. But she was out of step with the times. No political radical, she spoke from a position of considerable social privilege, and didn’t acknowledge the extent to which race and class limited women’s choices, nor how difficult it could be for them to succeed professionally in a working world dominated by men. Women across America were beginning to realize that what they needed was not individual happiness, but collective change.

Yet there is still something subversive in Hillis’s call for women to live exactly as they chose — to “be a Communist, be a stamp collector, or a Ladies’ Aid worker, if you must, but for heaven’s sake be something!” She was radical in her awareness that singleness was not just the happy, voluntary, temporary state of the young but that older women, widows, and divorcées had a right to their own pleasure and needed to defend it throughout their lives. Even today, it’s hard for a woman to declare that she has made her choice to live alone, and not have people assume it’s a fallback option, or denial, or just what she’s doing until she meets someone. There are still limited ways of talking about happiness, fulfillment, and a good life outside of the model of the nuclear family. As Marjorie Hillis preached, exercising the right to live your life as you choose is still a political act.

Joanna Scutts is the author of The Extra Woman: How Marjorie Hillis Led a Generation of Women to Live Alone and Like It.