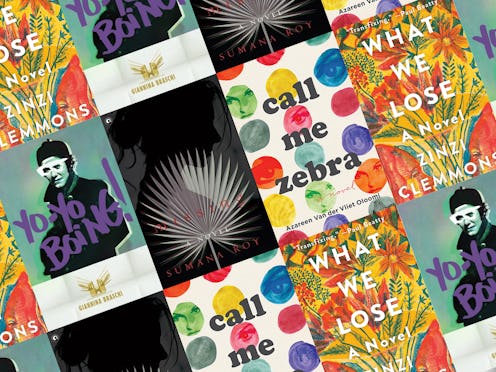

Books

How I Learned To Love Experimental Fiction By Seeking Out Books By Women Of Color

During my third summer in Columbus, Ohio, where I came from Kolkata, India, to study postwar experimental literature, I was reading the Puerto Rican author Giannina Braschi’s novel Yo-Yo Boing! in a nearly empty café. I came across a section that read: "Now try and say I’m not a muse. I bet no writer has done it yet. Not even Henry Miller, who bragged about whoring the whores with pen in hand, with both instruments moving along… It was a lie." I guffawed reading it, loud enough for a young man across from me to remove his headphone and stare, a mix of curiosity and annoyance on his face. I showed him the book’s cover. He said, “ha-ha funny book?” I responded, “In a way, yes.” That was the most I was willing to explain my fit of laughter brought on by Braschi’s parody of the writing-related fantasies of male authors, like Miller.

Experimental fiction questions language’s representational abilities and plays with formal rules to challenge established systems of power. These books defy stylistic conventions associated with both genre fictions and traditional realist literature. In rebuking orthodox institutions, experimental fiction come across as provocative and iconoclastic. Yet, white, male authors often perform their dissent by sustaining illusions of possessing or plundering language imagined as the female body. In the line I quoted earlier, Braschi is parodying a metaphor that equates the woman’s body with the white sheet on which the male author writes with his pen — and his penis.

That was the most I was willing to explain my fit of laughter brought on by Braschi’s parody of the writing-related fantasies of male authors, like Miller.

The trouble is, I love experimental fictions. When I first read self-referential, irreverent writings of Italo Calvino and William Gass, I was drawn to them, despite the generous doses of sexist fantasies contained within them. When I moved to the United States to attend grad school, I resigned myself to the fact that many significant works of experimental fiction feature women characters who are stalked, groped, and abused. The authors do so to first set up, then attack, relations of power. However, something changed when I came upon Braschi, which eventually led me to seek out contemporary experimental fiction by women of color. I had never seen Yo-Yo Boing! mentioned in reviews or surveys of experimental fictions, either academic or otherwise. It made me wonder what we talk about when we talk about experimental writing.

Is it an accident that experimental fictions often concern white, male authors’ anxiety about how ordinary uses of language represent parochial worldviews? Or, is it that only white, male authors’ anxiety of representing parochial worldviews, expressed by upending the rules of language, form, and genre, earn the label “experimental”? Why does the roll call of experimental prose read James Joyce, William Gass, and William Gaddis, and not authors of color like Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Giannina Braschi, and Pamela Lu?

It made me wonder what we talk about when we talk about experimental writing.

When women, particularly women of color, break conventions associated with writing, they are understood to be expressing something essential about their identity; they are presenting the Asian experience, the Black experience, the feminine experience, but they are not said to be innovating literature as a white, male author would. This is perhaps why Toni Morrison’s Jazz is not thought of as an experimental novel, even though Jazz transfigures the so-called omniscient narrator.

Today a new generation of women of color are challenging the rules of traditional, realist literature, while also citing and parodying the genealogy of experimental writing. Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi’s Call Me Zebra is a prominent example of this. Oloomi crafts a young, female narrator who is born in a library, exiled from her country of origin, Iran, and, eventually, orphaned. The narrator calls herself Zebra and goes on a grand tour of exile, following in the footprints of the great writers she grew up reading. Zebra’s father told her that she comes from a long line of fearless thinkers. However, all of these intellectual ancestors are male. Zebra seems to be both proud of “metabolizing” texts from Cervantes, Borges, Nietzsche, Omar Khayyám, and others, and anxious about her appetite.

Oloomi isn’t the only one challenging the rules. In H & G, Anna Maria Hong delivers an innovative rewriting of the fable of Hansel and Gretel. She chronicles the exploits of the “girl-hero,” characterizes the witch as a conscientious citizen, and asks readers to consider "What is the crumb/diamond of this story?" The answer: "You are G. writing a novel about patricidal hatred, inherited misogyny, and looking for good kin./ you are G. as little Korean American Fräulein."

Today a new generation of women of color are challenging the rules of traditional, realist literature, while also citing and parodying the genealogy of experimental writing.

Identifying her authorial self with Gretel, Hong writes, "In the fantastical world we are watching/ the Black women are victims, the White women are sluts, the Black Men are violent monsters, the White men are brave heroes, and the Asian men are inconsequential." I dwell on Hong’s choice of the word “fantastical.” It is a reminder that stereotypes in fiction are expressions of limited imagination.

Thandi, the "light-skinned black woman" narrates Zinzi Clemmons’s What We Lose, also thinks about ancestry and observes that "our heroes tend to be orphans." Thandi uses lists, images, and journal clips to find a language that can describe the "direct experience" of losing her mother and becoming a mother to the child she calls M. The sound of the letter "M" harkens to the first words typically uttered by a child — Ma, Mama, Mom — however, the first word M actually utters is "sh*t."Clemmons’s meditative prose dilates and sutures time, and the plot is cyclical.

Sumana Roy’s Missing also has a visceral phonetic logic holding up the story. The book gives the sensation of treading a linguistic surface that has other sounds streaming underneath it. The groundwater running under the English language tastes of my mother tongue — Bengali. In the novel, Nayan (meaning “eyes” in Bengali) is a poet who has lost his vision as well as his wife, Kobita (“poetry”). Missing is about what language misses when it tries to represent or report, the caesura in a line of communication. Guadalupe Nettel’s After the Winter and Bhanu Kapil’s hybrid writings also push the limits of language and fantasy.

After circling the patrilineal axis of experimental fictions for many years, I am now “looking for good kin,” as Hong says, and finding possibilities among contemporary women authors — primarily, women of color — who are orphans, in a sense, but also, kin to one another.