Books

'The Odyssey' Has FINALLY Been Translated By A Woman. Here's Why That's So Important

The first English translation of The Odyssey appeared around the year 1615. The first translation by a woman came out on Tuesday.

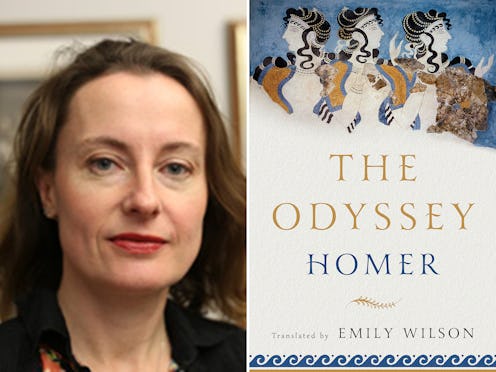

After several centuries and 60-odd English translations of the ancient Greek epic, Emily Wilson has made history as the first woman to ever tell the story of Odysseus and his arduous journey home in the English language. Perhaps just as momentous as shattering this classical glass ceiling, Wilson has brought an ancient epic into the year 2017. Her translation is lyrical, radically readable, and as politically relevant as ever.

"I guess I first encountered the story of The Odyssey in a school play, when my elementary school put on a version of it and I got to play Athena," Wilson tells Bustle. "I loved the story, I loved getting to dress up as a goddess, and that then made me want to read the kids’ adaptations of Greek myths."

Her childhood passion only deepened when she hit high school and was able to study Latin and Greek texts firsthand.

"I loved Latin, I loved the structure of the language, the sound of it," Wilson says. She loves the way that the stories engage with such crucial issues of life and death, too: conquered cities and vengeful gods and questions of national identity. "And I started taking Greek in high school as well, and that was also mind-blowingly amazing. Reading Plato and Euripides for the first time, it felt like a kind of conversion experience," Wilson says. She was enthralled by "this access to these alien cultures, which are both so totally different from the culture that I was living in and also so deeply relatable. I found that really exciting."

The Odyssey by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson, $30, Amazon

In taking on The Odyssey, Wilson's interest was primarily poetic. She didn't set out to break into the Homeric boys' club. "When I signed up to do the project, I hadn’t actually realized that I was going to be the first woman," says Wilson. "I wanted to do a translation that was going to have its own kind of music and have a regular meter, which most of the current translations don’t have."

She also wanted her translation to have clarity for modern readers, and to avoid sounding overly pompous. "Most of the translations that are out there equate being epic and being ancient," she says. "I just don’t think that quality has to be showing off. It’s a false equivalency."

"Which maybe actually has to do with gender," she adds. Or at least, the fact that so many male translators take the more pompous route has to do with gender "on the down-low," she says.

Of course, being the first woman to translate one of the foundational texts of Western literature carries with it an enormous amount of pressure. Wilson may not have intended to write the definitive feminist translation, but her reading of the poem was always going to explore gender on some level.

"I’ve always had mixed feelings about Odysseus as a protagonist," Wilson says. "And I think this text—it too has mixed feelings about its protagonist. It too has an interest in drawing out the stories of the people who aren’t him. And of tracing the ways that Penelope’s perspective, for instance, is totally different from Odysseus’ perspective."

And not only Penelope's perspective: The Odyssey is full of women. There are female monsters, goddesses, witches, slave girls, princesses, and a giant, female-identifying whirlpool. Odysseus even has a sister lurking around in the background of the text. "I hadn’t ever noticed before," says Wilson, "Odysseus has a sister. She’s only mentioned once in the poem, but I hadn’t noticed her the first few times I read the book!"

Odysseus' sis may not leave a major impression, but some of the other minor female characters are actually quite significant. "People always just go straight to Penelope, but it seems to me that the poem is so interesting partly because it has so many different female characters and so many possibilities for how to be female," she says. So much of our media tries to squeeze all of womankind into a single archetype. "Like in Smurf village where there’s just 'Girl Smurf.'"

The Odyssey presents many models of femininity beyond Smurfette, though. "There’s more than one way to be a girl," says Wilson. "I love that about it. For instance, the goddess Calypso, she’s such a wonderful character... She’s able to articulate that there is a double standard on Mount Olympus." Calypso gets in trouble for keeping Odysseus as a lover on her island, but, as Calypso herself points out, Zeus gets away with that sort of thing all the time. "It’s not fair how the gods judge their own love affairs with mortals by one standard, and the love affairs of goddesses and human beings by a totally different standard," says Wilson, "And I love that the poem is able to at least have that moment where a female character is totally powerful and totally able to say, 'There’s a problem here, with how we’re doing this.'"

The most important god of The Odyssey is also a woman. At least, most of the time. "I love that the presiding deity is a female," says Wilson. "In this poem, it’s about Athena. She’s female, but she’s also gender fluid." Indeed, Athena seems to regard the gender binary as more of a loose guideline than an ironclad law. "She’s being a man, and then being different men, and then she’s a little girl, and there’s one moment where she switches from being a young man to being a beautiful woman," says Wilson. "Could it be that she’s just as powerful or more powerful when she’s female as when she’s male? Or when she’s a little girl and when she’s a young man? There seems to be some openness to what the human possibilities are, in terms of gender roles."

Even the lady monsters have a certain amount of inspiring power. "We have all of these female and feminine monsters," says Wilson. "All this focus on the fear of female enclosure, the fear of being eaten or being drunk by a feminine creature. There’s the voices of the sirens that are going to engulf [you], there’s Charybdis, the whirlpool, that is going to engulf [you], going to eat up the men—there’s a fear of femininity that’s going to devour you."

Being a monster doesn't necessarily have to be a deal-breaker, though. They might be fearsome, but they command respect. "They’re presented in ways that are powerful," says Wilson. "And very attractive and seductive."

As for the enchantress Circe turning Odysseus' men into pigs? “It’s awesome," Wilson says. "I love it.”

Of course, it's not all gender fluid goddesses and powerful feminist subtext. Wilson's translation does not flinch away from the ugly nature of sexism in The Odyssey, either. After Odysseus has finally made it home and killed all of his wife's suitors, he orders his son to execute the slave girls who have been sleeping with the suitors as well. “It’s about eradicating not just these unclean bodies, but also, and I think this is very clear in the text, it’s about eradicating their memories," says Wilson. "They have a memory of the house possessed under different ownership. In order to get rid of that memory, that history, these women and their voices have to be suppressed.” It's quite literally a moment of women being silenced by male violence.

The slave girls only want to go home and go to bed, the same thing that Odysseus has been trying to do for the last 10 years. But the girls are murdered on Odysseus' orders instead. "We’re allowed to feel horrified by that," says Wilson.

Perhaps this is why Wilson chose "complicated" as the word that describes Odysseus in the opening line of the poem. Previous translations have called him "crafty" or "adventurous" or "skilled in all ways of contending." To Wilson, "complicated" just about sums it up.

“I wanted to make clear that this is a multi-layered character. And they might not necessarily be all positive layers," says Wilson. “There’s a multiplicity of perhaps a disturbing kind both about this character, but then also about this story.”

Not only is The Odyssey complicated, it's startlingly relevant. The worries of the Ancient Greeks are not so far off from our own. For one, the original Odyssey was set down as the Greek people were encountering people who weren't Greek. “I think it’s to do with how we treat people from different cultures. How do we live in a multicultural society?” says Wilson. "I hadn’t thought of The Odyssey as a poem that’s about immigration and refugees, because I hadn’t been reading it at this particular moment in history before. We weren’t in this particular moment in history before." Reading it now, though, the comparison seems clear.

And of course, the question of how we define gender roles is just as pressing in 2017 as it was in the 8th Century BCE. "In this poem, we have this sense of the Odysseus and Penelope marriage, and he has so many choices and so many things he can be," says Wilson. "And she only has one choice, which is either to stay married or marry someone else. And that’s it. And it’s figured as being faithful or being unfaithful. There’s judgment attached to it."

The poem, in Wilson's mind, asks us the question, “Do we want all women to be curtailed in the way that Penelope is curtailed?” Penelope is trapped. “In her dreams she goes to these amazing places, and she’s obviously so intelligent and alive,” Wilson says, but in reality Penelope spends her days weaving and un-weaving her own work, never moving forward.

If we could speak to Homer himself, it's unlikely that he (or whoever else wrote the poem) would come out in favor of women's equality. "But I think the poem itself points to some of the problems in the curtailed women’s roles it depicts," says Wilson. And the glimpse of so many different models of femininity, from goddess to sea monster, suggests that there are other options for women.

The Odyssey can speak to male violence, too, as well as female oppression. “It’s relevant that the climactic scene of this poem is this massacre in a domestic space,” says Wilson.

The weapon that Odysseus uses is, according to her, “not the kind of bow you just get from your local bow store, it’s the kind of bow that you use for a mass shooting.” Odysseus uses his bow to slaughter Penelope's suitors in a gruesome, gratuitously violent homecoming.

“It isn’t totally an act of justice," says Wilson. "It’s also clearly connected to the ways that, for instance, the Cyclops earlier behaves by killing the people who’ve invaded his house. The Cyclops eats the men who’ve come inside his cave, because you shouldn’t enter somebody’s house without permission. And then Odysseus does the exact same thing: kill the people who’ve come inside his house without permission.”

The questions raised by Odysseus' final massacre are only too topical, especially in America today: “What causes people to be so violent? What causes people to feel so angry and so murderous that they can’t get a sense of belonging or identity without killing a lot of people?” Odysseus is our hero, yes, but that doesn't make his actions uniformly heroic. He is, for lack of a better word, complicated.

Emily Wilson's new translation of The Odyssey is not just a landmark for a feminist reading of the poem, but for a contemporary reading. Her words are groundbreaking in their clarity as well as in their insight. And for anyone who thinks that a 2,800-year-old text doesn't have anything new to say, allow Emily Wilson to set you straight.