Books

How Books Became A Lifeline For Me And My Teenage Parents

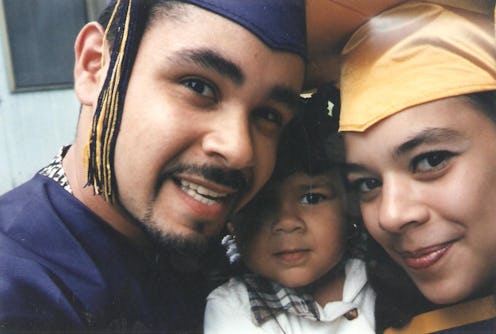

My mother was 14 years old. She weighed less than 100 pounds, sprayed half a can of Aqua Net in her hair every day, and was in love with a short, handsome Puerto Rican boy two years older than her. The pair were so inseparable that when the boy didn’t make the basketball team, he signed up as the waterboy just to watch her cheerlead. But the innocence of their puppy love vanished on the second day of their freshman year of high school. On that day, the young couple discovered that they were pregnant with a baby. That baby was me.

My mother depends on routine. Patterns keep her productive, and repetition gives her reassurance. As one can imagine, pregnancy disrupted her routines, and health complications made it difficult for her to make it to school everyday. For both her safety and mine, she completed her freshman year of high school from home with weekly visits from a select group of teachers, one of whom spoke to her about how much her own daughter loved reading. "She told me if you do nothing else, make sure you read to her," my mom says. And so, while I was still in the womb, my mother did just that.

She started with pregnancy books, reading to me about how I should be growing and developing. She learned I could hear her voice, and so she started reciting her Spanish homework aloud. The rolled r’s would make me do backflips inside her, but her history assignments put me to sleep. She read everything she could get her hands on and encouraged my anxious father to do the same. My mom tells me my father was so nervous about parenthood that he spent the beginning of her pregnancy avoiding the topic entirely. "But when I was about 6 months, I woke up from a nap, and his head was on my stomach. He was talking to you," she says. "It made me happy, because I felt like it was confirmation he was ready for you."

The reading routine stuck, and my mother continued to read to me after I was born, so much so that I memorized Barney and Baby Bop at the Beach and convinced my relatives I was a toddler that could read. "You used to imitate exactly how I read it," my mother tells me. "It left everyone amazed." My father would sit with me, and I would instruct him to flip the pages in the same tone my mother used with me. The books poured in as relatives gifted me box sets of Peter Rabbit, Disney Stories, and Dr. Seuss. The volumes filled my mini bookshelf and overflowed into the toy chest my father made me in woodshop. Every night, at least one of my parents read to me.

"She told me if you do nothing else, make sure you read to her," my mom says. And so, while I was still in the womb, my mother did just that.

In reading, we found security and routine. It was the one thing that happened everyday, regardless of mom’s long shifts at McDonald’s or the pile of homework she and my dad had to get through each night. It was what kept me and my mom cuddled in bed together while my dad worked his second shift. It was what reminded my parents they were capable of teaching me while still learning themselves. My mother tells me she read to me so I could see people and places I wouldn’t encounter in our urban city. “I didn’t want you to be like everybody else here,” she tells me, “And if I didn’t read to you, you threw a fit.”

My parents married two months after I was born, but their childhoods had been cut short and they were forced to grow up too fast. They were overworked, stressed, distant. After six years of marriage, they filed for divorce, and my father moved out of our apartment. Now single, my mom now had to work even longer hours to keep a roof over our heads. She was often too exhausted for our reading time. But books continued to be my sanctuary. On the weekends, my mother would catch up on her sleep and take naps in her black canopy bed. I would slide in next to her with a book, reading aloud to the sound of her light snoring. When she woke up, I sometimes read it again, while she nodded in approval or corrected my pronunciation. During the long drives she took to clear her mind, I would read Junie B. Jones in the backseat until I fell asleep. On the days when she had no choice but to bring me to work with her, I would lose myself in Nancy Drew novels in an empty office. On nights when she had to camp out in her college library to finish her class work, I sat across from her with Chicken Soup for the Kids Soul in hand. Books gave us routine when everything else was in fluctuation. Literature was the friend that accompanied and entertained me anywhere, including my visits with my dad.

It was what reminded my parents they were capable of teaching me while still learning themselves.

My father thrives in social settings. He loves to be surrounded by family and enjoys having a crowd to listen to him. My weekends with him as a kid were often spent at a family gathering, with my relatives shouting at each other over music and my cousins running the apartment. These loud and chaotic visits were so different from the calm routine of life with my mother, and I often felt overwhelmed. I usually hid in a corner to escape into a book and quell my anxiety as the party continued. My father often seemed perplexed by my desire to get lost in a novel when I could celebrate with family, but I think he understood that written words were my comfort when I didn’t know what to say or how to interact with others. "I could tell it was an escape for you," he tells me now, "But I didn’t mind. Instead of you getting lost in the world, you got lost in your books."

On the weekends, my mother would catch up on her sleep and take naps in her black canopy bed. I would slide in next to her with a book, reading aloud to the sound of her light snoring.

We began to spend our Sundays at Barnes & Noble. My father would walk me to the children’s section and sit in the storytime space as I skimmed the aisles. Eventually, he would sneak off to the periodical section to read car magazines. After I found a story I wanted to take home, I would meet him by the magazines, book in hand. “Find something?” he’d ask. After a silent nod, I’d hand him the book, he’d flip it over to check the price, and we’d head to the cash register. Eventually, I made my way to the young adult novels. During each car ride back to the bookstore, I would ramble to him about the last Sarah Dessen story I read or the next Bluford High book I hoped to grab. My toy chest-turned-book bin no longer closed and the Twilight series held the lid open. I don’t think he ever actually listened to what I said, but I remember how earnestly he would smile and nod along. Just as books had filled the uncertainty my mother and I faced, they also filled the silence between me and my father — a young man who was trying to get to know his daughter two days at a time while also trying to get to know himself.

Like most teenagers, I distanced myself from my parents and eventually began going to the bookstore alone or escaping to a coffee shop to re-read The House on Mango Street. One summer, after I had moved to New York for college, my toy chest became covered in mold, and the books inside were ruined. My mother broke the news to me as I sat on her couch, distraught. "But I managed to save one,” she said, pulling out Barney and Baby Bop at the Beach. We laughed as I cried, not from sadness but from gratitude for all the memories and comfort that literature gave me and continues to give me. I thank books for the car rides with dad when he still asks me what I’m reading and for the visits home when mom and I snuggle up on the couch with our stories. On my best days, I drift into a bookstore to choose a book out of celebration. On my worst days, I drift into a bookstore to seek the solace I felt as a child. Books brought my unconventional family routine when we were scattered, direction when we were lost and connection when we were distant. By the grace of literature, we have figured out life together.

This article was originally published on