Books

How 3 Rom-Com Authors Are Tackling Abuse & Trauma In Their Novels

In all of the best romantic comedies, there is an undeniable thread of heartache. Sure, rom-coms are filled with adorable meet-cutes and dramatic declarations of love, but in some of the most genre-defining books and films — To All the Boys I've Loved Before by Jenny Han, Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan, Dumplin' by Julie Murphy — the stories blend romance and lighthearted banter with depictions of profound grief, tragic loss, and deep trauma.

"I think that a lot of the best romantic comedies have an element of sadness to them," Linda Holmes, author of Evvie Drake Starts Over, tells Bustle. "One of the things about the real love of other people is that it helps balance things that are painful. Not solve them, just balance them."

In retrospect, it is not surprising that rom-coms have found their way back into the mainstream.

"I think it’s wonderful that rom-coms are experiencing such a revival, and I believe it’s a response to our increased awareness of all the negativity in the world," Talia Hibbert, author of Get a Life, Chloe Brown, says. "Everything’s on fire and we know it, so romance and humor and happy endings are a welcome escape. But, at the same time, it’s impossible to turn away from pain and suffering — especially if you yourself are going through it. That’s where rom-coms become not just an escape, but a tool of comfort and healing."

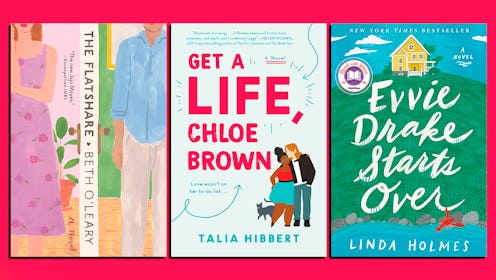

Three of 2019's biggest romance releases — Holmes's Evvie Drake Starts Over, The Flatshare by Beth O'Leary, and Hibbert's Get a Life, Chloe Brown — do just that, through exploring the effects emotionally abusive relationships have on their characters. Each of the three authors tackles abuse and its aftermath in a slightly different way: In O'Leary's novel, Tiffy is coming to terms with the extent of an ex-boyfriend's gaslighting; Holmes's Evvie is dealing with the loss of a husband who often yelled at and belittled her; and Hibbert's protagonists, Chloe and Red, are both coping with PTSD in the wake of bad relationships.

"I just wanted to write a love story that felt truthful," O'Leary says. "It seemed natural to me that these two people in the mid-to late-twenties would be coming to their new relationship with a history that has shaped how they think about love. I never consciously thought about weaving darker topics into the story."

A 2005 study by the National Coalition of Domestic Violence found that 48.4% of women have experienced one or more psychologically aggressive behaviors by a significant other. And 35% of all women who are or have been in married or common-law relationships have experienced emotional abuse. The numbers in England, where The Flatshare and Get a Life, Chloe Brown are set, are similar: In a 2015 study, 27.1% of women reported that they had experienced domestic abuse since the age of 16.

"For a long time, romance has been well-versed in talking about abuse and trauma and the importance of support."

Living in an emotionally abusive relationship is an experience that many women reading rom-coms have known personally, and romance novels can be a tool for working through these shared experiences and traumas.

"Women are the majority of both the reading and writing demographic of romance, and they have always known about these things — abuse, harassment, men who are controlling," Holmes says. "A lot of romance novels have elements of abuse in them [and] have long shown women recovering from trauma or being freed from toxic relationships. For a long time, romance has been well-versed in talking about abuse and trauma and the importance of support."

While it is true that romance authors have always written about consent, abuse, and assault, it is not necessarily true that readers have always had easy access to these texts.

"Marginalized genders have always written these evils into our romances, because that’s what a lot of writers do: We exert control over our realities through our work," Hibbert says. "But, how many of those romances did readers see? Or rather, how many were purchased and published and promoted? Some, but not a ton."

Hibbert points to continued concerns over diversity in romance as part of the reason for the lack of rom-coms that deal with trauma, abuse, and toxic relationships. The Ripped Bodice's 2018 State of Racial Diversity in Romance study found that for every 100 books published by the leading romance publishers in 2018, only 7.7 were written by people of color. And when it comes to books that deal with abuse, Hibbert wonders whether publishing is truly ready to discuss things like "the impact race has on sexual abuse, disabled victims of sexual abuse at the hands of their carers [and] prioritizing queer victims whose trauma doesn’t fit cisheteronormative parameters."

"I remember very vividly the experience of scrolling through social media and seeing these incredibly brave people sharing their stories, and thinking of Tiffy..."

It is also undeniable that these novels — whether directly inspired by the #MeToo and Time's Up movements or not — are being released into a world where these topics are now front-page news. These movements are undoubtedly changing how people read romances, and how authors write them, too.

"I actually wrote The Flatshare before those movements began," O'Leary says, "and I remember very vividly the experience of scrolling through social media and seeing these incredibly brave people sharing their stories, and thinking of Tiffy, and how it might have been easier for her to see the truth of her past relationship if she’d been in a post #MeToo world. I love that consent and control are being discussed more in romantic fiction. If we’re talking about it there, hopefully we’re talking about it in our own real-life love stories, too."

Equally important, too, is the fact that authors are not just exploring the abuse that women endure in romantic relationships, but men, as well. According to The National Domestic Violence Hotline, nearly half of all men, or 48.8%, in the United States have experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

In O'Leary's The Flatshare, the male main character, Leon, deals with a girlfriend who belittles him and his interests (particularly when it comes to his efforts to free his wrongly-incarcerated younger brother) and is often haunted by memories of the abusive relationships his mother endured throughout his childhood. In Hibbert's Get a Life, Chloe Brown, while Chloe deals with the after-effects of a partner who did not believe she had a chronic illness, it is the male main character, Red, who suffers from severe PTSD caused by a former girlfriend's gaslighting and abuse.

"Because misogyny limits the humanity of the ‘ideal’ man, stories with abused heroes haven’t always been appreciated like they should be," Hibbert says. "I also knew, from observing other, less thoughtful media, that survivors are often seen as less masculine. That narrative is a disgraceful pile of ignorant bullsh*t, so I decided to ignore it in favor of reality — the reality being that men are humans and humans hurt, and there’s nothing wrong with that."

"One of the hardest things about gaslighting is how tough it can be for victims to recognize what's happening, as their own perceptions are being distorted."

Crucially, the characters in these books — particularly Hibbert's Red and O'Leary's Tiffy — are slow to realize the depths of the abuse they've experienced. Their truths are unraveled in a way that surprises the reader as much as the characters themselves. It's a reflection of the way that gaslighting and abuse usually reveals itself in real life, too.

"One of the hardest things about gaslighting is how tough it can be for victims to recognize what's happening, as their own perceptions are being distorted," O'Leary says. "I didn't want to just tell the reader that Justin [Tiffy's ex-boyfriend] had been emotionally abusive, I wanted us to learn it, maybe even feel a little surprised at not spotting it sooner."

"It is always the right time for romance to embrace the reality of its readers."

For a long time, romance novels have provided women with a means to express their oft-belittled internal lives, their desires, their triumphs, and their struggles.

"Publishing, like all industries, has a responsibility to tell everyone’s story, and I’m pleased it’s trying to take that responsibility seriously," Hibbert says. "Whether our stories are seen or not, we will always write them. I sincerely hope that the social sun continues to travel across our landscape, taking everyone out of the shadows. It is always the right time for romance to embrace the reality of its readers."

This article was originally published on