Books

This New Memoir Is Basically A Rock Climbing Version Of 'Wild' & You'll Love It

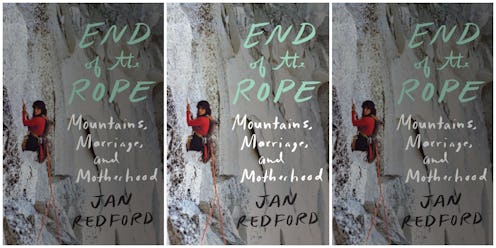

Jan Redford often describes herself as afraid; or occasionally, in her words, “chicken sh*t.” In fact, she’s actually kind of a badass — at least, the story she tells in the page of her debut memoir leads me to believe as much. That memoir is End of the Rope: Mountains, Marriage, and Motherhood, out from Counterpoint Press on May 8. End of the Rope tells the story of Redford’s journey from a young, world-traveling rock climber to a rural mother of two fiercely fighting for her right to an education. It’s a story filled with grit and loss, intensity and resilience, adventure and self-discovery, profound grief and immense wonder. And, yeah, you’ll love it.

End of the Rope opens with Redford literally clinging to the side of a mountain. Fourteen-years-old and angry at a father who had just moved the entire family to a cabin in the Laurentian Mountains of Québec, Canada (though mad because her father has excluded her from the “men’s work” of moving, not due to the move itself) Redford goes climbing. Filled with teenage fury she heads out on her own, ultimately free-climbing a crumbling, black lichen-covered rock face. I’m going to be a mountain climber when I grow up, Redford writes in her diary that night.

The anger that propelled a young Redford into the adventure of her life is one that recurs throughout the memoir. Anger seems to be one of the climber-turned-writer’s motivating forces throughout End of the Rope — beginning with that first wall climb and threading itself throughout Redford’s future decisions. In a cultural moment where women’s anger is, hopefully, being validated more than ever before, it’s refreshing to read a writer exploring her own so thoroughly on the page.

“Anger gives me a backbone,” Redford tells Bustle. “Even thinking about being angry makes me sit up straighter. It’s my favorite emotion, but one I still have trouble accessing. It’s an emotion of defense, of strength, of dominance. That’s why women aren’t supposed to be angry. Why it’s ‘unfeminine.’”

End of the Rope: Mountains, Marriage, and Motherhood by Jan Redford, $24, Amazon

She’s mindful to distinguish between productive and unproductive anger — one that needs to be made more often, especially when discussing anger’s gender bias. “I’m not talking about throwing things or overpowering another,” Redford clarifies. “That’s not real, healthy, productive anger. That is usually a result of repression. Repressing anger is what slowly corrodes our spirit. I can attest to that personally. But when I feel healthy anger, and express it constructively, I feel like my inner protector is rising to the surface to be there for me. When I repress it, I repress my protector and I’m fair game. Anger, being such a strong emotion, usually leads to action. Movement. Coming unstuck.”

"But when I feel healthy anger, and express it constructively, I feel like my inner protector is rising to the surface to be there for me."

Gendered spaces and gender bias — not just of anger — is at the heart of End of the Rope. Redford, after all, spends much of the book clawing a path for herself in the boy’s world of extreme mountain climbing. In the first few pages of End of the Rope she notes wanting her father’s life. In romantic relationships, she describes wanting to be her partners, as opposed to just being the girl who is with them. I ask Redford about this: what it meant to be a woman in a culture of men, what it meant to seek out a life for which there were few-to-no female role models, and how that played out in her early relationships?

“It takes a long time to learn to parent yourself when you weren’t properly parented as a child,” Redford says. “I figured out pretty quick at age 18 when I went into the world that I was defenseless because I didn’t have an internal defender. I developed a very tough personae. I tried to be more macho than the guys — chewing tobacco was my most disgusting tactic. I called it my handy-dandy man-repellant but that didn’t seem to work. I was tough on the outside but I lacked congruence, which makes a person constantly on guard not to let others find out how squishy they are on the inside.”

“I found this all out with a very good psychologist,” she adds.

Redford’s relationships throughout the memoir are as up-and-down, as much journeys of self-discovery, as the rock faces she spent her young life climbing. She describes choosing tough, unavailable, confident, and skilled men who exhibited all the qualities she wished for in herself. “Maybe I thought I could become competent by osmosis,” she says. “Just by being near them. But I turned them into the parent I lacked internally. That’s a heavy responsibility for a guy, and most of them didn’t want to carry the parent torch. They just wanted someone they could swing leads with climbing.”

"I was tough on the outside but I lacked congruence, which makes a person constantly on guard not to let others find out how squishy they are on the inside.”

But, she says, calling upon the worlds of feminist icon Gloria Steinem, “ ‘We have become the men we wanted to marry.’ That is the journey I’m on. And it’s a goal I’m closer to now. But I have to almost make a checklist of everything I’ve accomplished in my life and pull it out regularly to remind myself that I really am quite competent. Go figure!”

Redford’s struggles with feminism resonate throughout End of the Rope as well. She calls herself a feminist, but notes the frustration she feels at not living up to the ideals of feminist leaders.

“I’ve written about being ‘the worst feminist to walk the earth,’ and ‘the poster girl for The Cinderella Complex,’ and ‘a non-practicing feminist.’ We have to struggle with our need for love, approval and acceptance with our need to walk the talk of feminism. It was and still is the “F” word in a lot of circles. And because we were created in this world, it can take a lifetime to grow into feminism.”

Growing up in the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, Redford shares her internalization of her parents’ relationship — the gendered power imbalance that she witnessed not only in her own family, but in the families of her friends as well — and the cultural messages that were (and often still are) sent to young girls and women every single day.

“I, like most of us, grew up with the statements: you run like a girl, you throw the ball like a girl, you cry like a girl — being the worst insults imaginable. What a message to receive day after day! And because of what I saw in my family, I rejected my mother’s life. Me being me, I took that a few steps further and rejected anything feminine: the color pink, dresses, heels, make-up, talking politely without throwing in cuss words. I was contemptuous of anything feminine because I associated it with weakness. Essentially, I rejected myself. I love the book: The Heroine’s Journey by Maureen Murdock. She clarified my journey for me. We separate from the feminine and identify with the masculine, then we go on our long, convoluted, bumpy journey back to embracing the feminine. I’m a better feminist now that I’m not trying to feel like a man. Now that I can wear fuchsia pink mountain biking shirts. I see openness, honesty, pink, softness, expressing feelings, admitting to fear, as strongly feminist.”

She adds: “The little girl next door wears a pink Cinderella dress, body armor, and a full face helmet riding her mountain bike around our cul de sac. That’s my ideal feminist.”

Nearly all of Redford’s climbing experiences in End of the Rope involve her battling against your own fear. But even after the devastating climbing deaths she faces, including the death of her boyfriend Dan, Redford keeps going. She keeps choosing to climb, even when near-debilitating fear threatens to overtake her.

“I seem to have a very deep well of optimism and tenacity to draw on. My parents were wounded by their own experiences, but were very strong people. I think my mother passed along her rose-colored glasses, and my father passed along his ‘Jesus Christ, quit your whining,’ glasses. I have a lot of internal conflict, but the belief in the goodness in life and in people always seem to win in the end. I’ve always wanted a meaningful life, not an easy one. Seems to be what I got. After my boyfriend Dan’s death, my father said, 'You won't know this for a while, but one day this will make you stronger.' That’s what has happened. I’ve thrown myself at life with a lot of enthusiasm, and I can write funny stories about that, and it’s true it has brought a lot of heartache. But it has also brought a lot of joy. That’s what shines through.”

"I have a lot of internal conflict, but the belief in the goodness in life and in people always seem to win in the end. I’ve always wanted a meaningful life, not an easy one."

The twin ambition to Redford’s life of climbing is her tireless pursuit of higher education — a desire she had to fight tooth-and-nail for, against a family, a husband, a lifestyle, and a culture that made higher education, especially for a woman, nearly impossible to achieve.

“Education came to symbolize power for me,” Redford says. “The power to be in the world as a competent, confident, skilled adult. It meant I could have a meaningful career and support myself and my children so I could be in my marriage by choice, not out of dependence. It is what gave me the courage to leave that marriage. Climbing made me stronger, then education saved me.”

Ultimately, Redford earns her degree, all while raising her two young children — and instilling that same reverence for education in them. “It gave me the feeling that if I could do that, I could do anything,” she says. “It really wasn’t the degree that counted. It was the process I went through to get it. It was the transformation along the way.”

End of the Rope is a must-read for any young woman challenged with forging her way in a space that is still largely dominated by men — be it in the world of extreme mountain climbing, the boardroom, or anywhere in between. It’s a tome to both harnessing and pushing against fear, and the power of arriving on the other side.

“The biggest lesson I had to learn, that I’m still learning, is that because I’m scared and self-doubting on the inside, it doesn’t mean I can’t just go ahead and do whatever I want anyway,” Redford says. “I can do it while being scared sh*tless. I believe my boyfriend, Dan’s words: ‘Fake it 'til you make it.’ If you stand up straight, walk like a big person even if you’re five foot one (and a half), you eventually feel like one. It makes so much difference how you move physically in the world; how you talk to yourself. Instead of saying: ‘Jan, you’re a chicken shit,’ I try to think of what my mother kept telling me: ‘Jan, you’re so much stronger than you give yourself credit for.’ We all need a mother inside us saying that.”

“I can do it while being scared sh*tless."

Anyone curious what Redford’s climbing life looks like now might be surprised to learn she'll express the merits of fear. “Sometimes being scared protects us from death and gory injuries. I didn’t have enough fear when I started climbing,” Redford says. “I climb more for the joy of the movement now, not the need to push myself too far out of my comfort zone. I push myself just to the edge of fear, which doesn’t take much. I’m nudging myself out of my comfort zone but not risking death or a life in a wheelchair. It's freeing that my ego isn’t as involved. It’s freeing to be older. I can climb for the love of climbing.”