Books

This New Memoir Is 'Kimmy Schmidt' Meets 'The Glass Castle' & It's A Must-Read

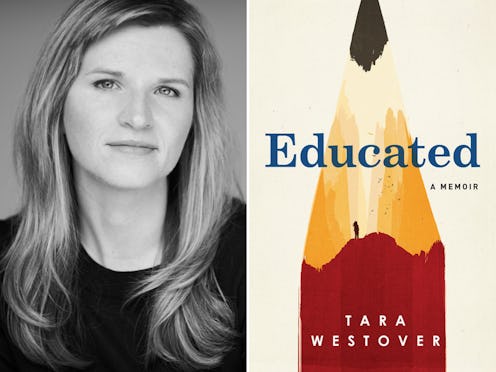

She’s been compared to memoir superstar Jeannette Walls and Netflix sensation Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, but Tara Westover’s story is wholly her own. In her widely anticipated memoir, Educated, out now from Random House, Westover tells the story of her unconventional — to say the least — upbringing: growing up in the mountains of Idaho without a birth certificate or a telephone, having never attended school or visited a doctor, raised by a survivalist father and a midwife and herbalist mother who dedicated their lives to preparing for the Apocalypse. Westover, herself, ended up at Cambridge.

But that journey from salvaging in her father’s junkyard on an Idaho mountainside to earning a PhD at one of the most revered universities in the world was hardly a straight or clear path. In Educated, Westover details the isolation, danger, and violence that led her to pursue a life outside the family compound; the intense culture shock she experienced — first as an undergraduate at Brigham Young University, then as a visiting fellow at Harvard, and finally as a doctoral student at Cambridge — upon leaving; and the devastating loss of her family, who couldn’t accept the different life she chose for herself.

It’s a story that’s both immediate and that transcends time — simultaneously speaking to the fiercely polarized and politicized space between America’s blue collar communities and educated elite, while exploring more timeless questions about family, faith, and following one’s heart.

“I wanted to tell a story about education in the way I experienced it — I think ‘educated’ is such a loaded word,” Westover tells Bustle. “For some people it has such positive implications and for others it can have negative or pretentious implications. I became aware when I was getting my education — and I mean education in the broadest sense, not just classrooms and exams, but the people you meet, travel, the things that you read on your own — that there is something odd about the way people talk about education, almost as a stepping stone on the social ladder: a way to get a better job, to make more money, to live in a better neighborhood. That just didn’t ring true with education in the way that I had experienced it. I don’t think education is so much about making a living, it’s about making a person. And that, to me, doesn’t seem to have anything to do with class or religion or any of the rest of it, because everyone should have the opportunity to participate in the making of their own mind.”

Educated by Tara Westover, $16, Amazon

Educated, while telling the deeply personal story of Westover’s young life and her decision to later pursue formal education, also speaks to the current political moment in the United States — wherein the divide between certain types of communities and others is being exploited for political gain. Westover has, in essence, existed at two extremes: first her family’s survivalist compound in Idaho and ultimately in the Ivy League and Cambridge. In Educated, she describes being interviewed after receiving the prestigious Gates Cambridge Scholarship, writing: "I didn’t want to be Horatio Alger in someone’s tear-filled homage to the American dream."

"I don’t think education is so much about making a living, it’s about making a person. And that, to me, doesn’t seem to have anything to do with class or religion or any of the rest of it, because everyone should have the opportunity to participate in the making of their own mind."

She notes the “weaponiz[ation]” of education. “I think one thing that is going on is really quite simple: access to a really good education is becoming something that is practically predetermined by who your parents are, where you live, and how much money you have. That alone is going to create a situation in which education is fracturing rather than unifying,” says Westover. “The idea of an education has become weaponized — access to a good education has become something that separates certain kinds of people from other kinds of people.”

Westover says she wanted to write a story about education that offered a different narrative. “I think sometimes our ideas about education are sterile and institutionalized. When we think of an education we think of a lot of very passive things: classrooms, and chalkboards, and exams," she tells Bustle. "It seems like we are complacent about education; we have ceased to see that it has any real power. The model of mainstream education is a little bit of a conveyor belt: you stand on the conveyor belt and you’re ‘educated’. I felt that the story of my life was an alternative narrative to that. Education is powerful, but power can mean change and change can sometimes mean calamity. It’s probably uncomfortable for some people to hear me talk about the calamitous power of education, but that really is how I experienced it. I mean, it cost me almost everything.”

Everything, meaning: her home, her parents, her siblings. Still, Westover says she’s grateful for the early education — of a profoundly different kind — that she received at home. “My parents gave my siblings and I the idea that you can teach yourself anything better than someone else can teach it to you, and that you’re responsible for what you learn. I mean, I think they took it a bit far. I’m not glad my parents didn’t educate me; I wish that my parents had taken education quite a bit more seriously. But that ethos and the way they think about education — that if people are not invested in the creation of their own curriculum, the creation of what they learn, they can’t possibly be invested in what they’re learning — that I am grateful for.”

It’s one reason Westover is resistant to the current safe spaces movement that is happening across university campuses. “There was absolutely nothing safe about my own education — nothing,” she says. “When the university becomes a place where certain kinds of well-off, already well-educated people congregate, and passively receive an education that reinforces the beliefs they already hold, that’s when an education becomes weaponizing, and polarizing, and just another reinforcer of identity. If education is going to be a true tool of self-creation and a way for people to actually challenge their ideas, this idea that education should be a safe thing has to go away.”

Something else Westover’s parents offered her — unlike her older siblings — was early exposure, however limited, to life off of the mountainside. As young girl, the writer discovered a talent for singing, and in Educated she describes the freedom her father gave her to perform in the local community, writing: "He wanted my voice to be heard." It’s an interesting moment in the memoir — illustrating something that many young girls, even those who don’t grow up in a conservative, survivalist family, don't necessarily get from their fathers. I ask Westover about this, how she understood that early validation that her voice had value — especially in contrast to the silence that would be ask of her later, as she began to move away from her home and the ideas of her childhood.

"If education is going to be a true tool of self-creation and a way for people to actually challenge their ideas, this idea that education should be a safe thing has to go away."

“I remember when I wrote that line, thinking about how ironic it was that he had wanted, so much, for my singing voice to be heard,” Westover says. “My dad was incredibly anxious about my spending time with people who didn’t think what we thought — he was very worried that I would get brainwashed, or that I would get seduced by the world, so to speak. The idea that I would be going over to town three or four nights a week, unsupervised, was pretty terrifying for him. It’s a liberty he would have never allowed my sister or my brothers. But I think because he so loved hearing me sing, and he so loved the attention I got from that, I was allowed to have these experiences with other kids and adults in the community. But then, later in my life when I grew up and starting thinking differently than he did, and began speaking in my own voice, that was not a voice he particularly wanted heard. I think that kind of duality defines my family. It certainly defines my dad. He’s a complicated person. It’s interesting that there was this context in which he really wanted me heard, and then there were other contexts in which he really didn’t.”

Still, those early moments on stage were formative. “I think the fact that I was able to sing had a huge impact on the way I conceived of myself, and more importantly on those things that I was allowed to do. It was a huge advantage in the way that I thought about myself, because I was standing there in the middle of a stage, singing, and everyone was listening just to me.”

Westover’s decision to pursue a formal education wasn’t the only thing that ultimately separated her from her family. In the end, it was speaking the truth about the violence she experienced — and witnessed, of others — at the hands of one of her older brothers.

“I was a bit surprised by what I thought would be difficult about writing a book,” says Westover. “I thought it would be difficult to write about my older brother — I was terrified of writing that, actually.”

Westover’s brother — an increasingly troubled, physically and psychologically violent young man — becomes a key figure in both why she left her family’s home in Idaho and why she was unable to return. “But that writing wasn’t terrifying. It was unpleasant but it wasn’t bad,” Westover continues. “I was so far removed from the person I had been that much of that story felt so far away. I knew I wasn’t stuck there and I could leave any time I wanted. So it was relatively easy to write those scenes, and then move forward, and leave the past where it belonged.”

The writing that she did find difficult was something else altogether. “The things that were hard to write about were the beautiful things: the way the mountain looked in winter, the sound of my mother laughing, the way that my dad used to tell these ridiculously absurd jokes — because these were the things that I had loved the most and that I had lost. So, it was really painful to write about them, to be that close to them, and to know that I wasn’t going to have them again. Kind of like attending the wedding of someone with whom you’re still in love. I think, in writing, I realized I had reconciled with the things in my past that had been bad, but I don’t think I had reconciled with losing the things that had been good.”

"The things that were hard to write about were the beautiful things..."

Ultimately, Westover says, she chose to wrote the memoir without a resolution. “I hope that allows people to attach to my story whatever narrative they need to help them come to terms with the decisions they themselves have to make — if they have a difficult family, if they find themselves in anything like the situation I found myself in,” she says. “I found when I was losing my family that I became very aware of the fact that we tend to get the same few messages about family and loyalty, over and over again. We have a lot of stories about family loyalty, but we don’t have a lot of stories about what happens when loyalty to family comes in conflict with loyalty to yourself. We have a lot of stories about forgiveness, but most seem to conflate forgiveness with reconciliation, or see reconciliation as the most desirable form of forgiveness. That hasn’t made sense to me. I had no idea if reconciliation was in reach for me, and I needed to find more complicated ways to think about family loyalty and forgiveness. I needed a more complicated story than that. And I didn’t really find it. So, I told the story."