Books

'Dust Bowl Girls' & Women's Fight To Be Athletes

When I was nine or ten, I would sit for hours watching men’s basketball (women’s basketball had yet to debut on TV). I even told Mom, who loved the game, too, that I wanted muscular legs just like those male athletes. She looked at me as if I had announced that I was from another planet.

“Girls aren’t supposed to look like that,” she said.

“Why not?” I asked.

“It’s just not ladylike.”

We’ve come a long way since that conversation with my mother: women’s sports have grown more competitive and popular. Interest in the 2015 Women’s World Cup rose 121 percent over 2011. The six matches that featured the U.S. team averaged 5.3 million viewers; the final game, U.S. against Japan, drew over 20 million viewers. According to a study sponsored by the USC Center for Feminist Research, 294,000 high school girls played interscholastic sports in 1971. Today, 3.1 million play, much closer to the 4.4 million boys participating in high school sports.

Title IX prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in any federally funded education program or activity. And yet, even today, top athletes like Serena Williams and Simone Biles are disparaged for their looks. According to the Tucker Center for Girls and Women in Sports, female athletes are much more likely than male athletes to be portrayed in sexually provocative poses. It’s heartbreaking and infuriating and not all that different from what women experienced decades ago.

I’ve spent the last several years researching the Oklahoma Presbyterian College (OPC) Cardinals for my book Dust Bowl Girls, a women’s basketball team from the 1930s. So when I read about Williams being mocked as too masculine, I think of how Babe Didrikson, one of America’s greatest athletes and the OPC Cardinals’ toughest opponent back in 1932, was described as boyish-looking, with the manners of a rancher’s hired hand. And it wasn’t just sportswriters who criticized her for her appearance. School teachers did, too.

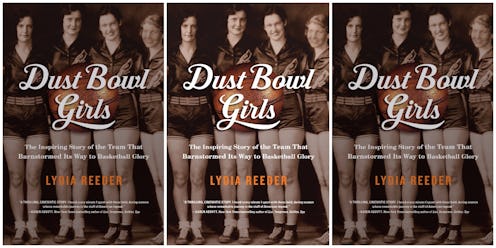

Dust Bowl Girls by Lydia Reeder, $10, Amazon

Back when the OPC Cardinals were winning games, top female athletes had to put aside their own fears about being publicly ridiculed to pursue excellence in the sports they loved. These athletes were pioneers exploring new territory that had been claimed by only men. And, they had powerful enemies.

Instead of being passionate mentors for young athletes, women who were influential physical educators fought to outlaw women’s competitive sports altogether. They launched a national campaign that resembled a religious revival aimed at eliminating aggressive team sports and saving the feminine souls of American girls. Their leader was Lou Henry Hoover, First Lady of the USA.

According to Hoover, young women should repress any desires to be star athletes because they were not “pioneers enough to discover their own possibilities.” In other words, a girl shouldn’t work too hard to get good at anything because by her very nature she didn’t have, and would never develop, the courage, power, and self-knowledge to succeed. Hoover labeled the general tendency to copy boys’ athletics with an emphasis on setting records and having championships “a cancer that must be killed.” (Women’s Division, National Amateur Athletic Federation, comp. and ed.)

This dark philosophy, that girls and women can’t be trusted to be in charge of their own bodies and lives, continues today. It has become the cancer that makes girls hate how they look or question their own abilities.

Even though millions of girls and women play sports every day, with tens of thousands competing in college and professional athletics, television coverage of women’s sports is sparse: media coverage of women’s sports in 2014 was only two to three percent. Hollywood has consistently overlooked stories about epic female athletes like Babe Didrikson, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, or the phenomenal 1999 USA Women’s World Cup Soccer champs. Compared to the barrage of information about male athletes, news about women’s accomplishments, past and present, is vague and distorted. We must do better.

We must embrace the emerging cultural norm about women athletes that buries outdated ideas about femininity. We need to know more about the champion swimmers; track stars; basketball, softball, soccer, and hockey teams; dogsled racers, golfers, and the myriad others who have plainly established that women are winners. Historic champions like the OPC Cardinals and current badasses like the Williams’ sisters, Ali Krieger, Simone Biles, Ali Raisman, and Sue Bird should be celebrated, not for their hair styles, clothing, or makeup, but for their pioneering spirit, perseverance, and athletic prowess. By inspiring young girls to strive for greatness, they are winning that epic battle, started years ago, for the right to have strong bodies and even stronger spirits.