News

Merriam-Webster's Editor At Large Talks Trump & NOT Trolling

It is hard to think of a politician — or any political figure — who is easier to troll than Donald Trump. Just a cursory glance at Twitter shows that there is no shortage of snark aimed at the Trump administration from pundits, journalists, and even other elected officials. But a somewhat surprising source of shade has emerged in the Twitter-verse: a beloved dictionary company. Merriam-Webster's tweets about Trump administration officials' use of words have earned the iconic lexicon resource social media buzz.

In under 100 days of the Trump presidency, Merriam-Webster has already sent some White House-related tweets that have become their own news story. They follow the basic structure of simply tweeting the definition of a word that Trump or one of his advisers or officials used — a word that has gotten attention for being used in a way that does not necessarily align with the traditional usage.

For example, when Trump senior adviser Kellyanne Conway said in February that, "It's difficult for me to call myself a feminist in a classic sense because it seems to be very anti-male, and it certainly is very pro-abortion, and I'm neither anti-male or pro-abortion," Merriam-Webster tweeted the definition of "feminism" a few hours after the remark:

When CBS' Gayle King asked Ivanka Trump for her response to critics who argue she has been complicit in her father's administration, the first daughter said, “I don’t know what it means to be complicit, but you know, I hope time will prove that I have done a good job, and much more importantly, that my father’s administration is the success that I know it will be."

Well, Merriam-Webster certainly knows what it means to be "complicit" and tweeted the definition:

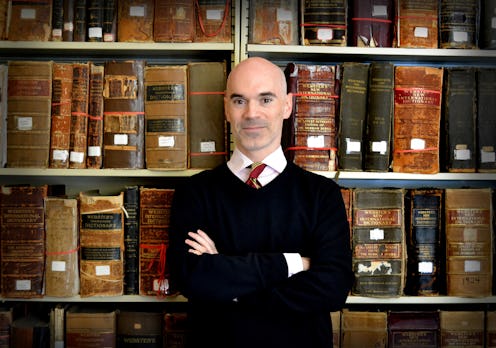

However, while many see these tweets as grade-A trolling, Merriam-Webster's editor at large, Peter Sokolowski, is adamant that these tweets — or any of the dictionary's commentary — is not intended to be partisan or interpreted as critiques.

"Of course, not. No. That would be counter to everything that we stand for. We've been in business since 1831. We're here to do research about language," Sokolowski tells Bustle when asked if Merriam-Webster has a political agenda to its social media presence.

"We don't cover the Trump administration. We cover language," he says. "It just so happens that the language that people are looking up these days or the big stories of the moment happens to be politics."

As Sokolowski explains it, the way Merriam-Webster chooses to feature and define specific words in its tweets is actually objectively based on what users are searching. "What you're seeing is a data-driven feature we call 'Trend Watch,' which reports on the words people are looking up," Sokolowski explains in a separate email. "When a word is suddenly being looked up at a much higher rate than normal, often in a way that’s clearly connected to an event, that’s a trend and we report on it."

While he understands why people are quick to perceive Merriam-Webster as taking aim at Trump, Sokolowski thinks people are missing the deeper meaning of the searches. "The superficial thing is [to say] 'The dictionary is trolling Trump.' It is true the dictionary can call balls and strikes about definitions and meanings because that's what we've always done," he says. "But the more profound fact is that these words, or these utterances, or these news stories have driven people to the dictionary, have caused curiosity, have put meaning into question."

Sokolowski is also quick to point out that last week, search for "volunteer" spiked because of the United Airlines incident when passenger David Dao was forcibly removed. The company initially stated the removal captured on the viral video occurred, “After our team looked for volunteers, one customer refused to leave the aircraft voluntarily and law enforcement was asked to come to the gate.” Unsurprisingly, many questioned how United Airlines used "volunteer," and search for it skyrocketed.

While the story wasn't political, Merriam-Webster responded with the same treatment it had for Ivanka Trump's use of "complicit," or Conway's use of "feminist" — or, for that matter, Conway's use of "fact" when she made her infamous "alternative facts" comment shortly after the president was inaugurated.

"We do not focus on words in the news as individuals and say 'Hey, this person used this word, we'll correct them.' That's not at all what's happening," Sokolowski stresses. "We see that tens of thousands of people are looking up the word 'fact' in a matter of a few hours. We see that something in the culture has driven them to the dictionary."

Since Merriam-Webster made its dictionary available online in 1996, Sokolowski has noticed search spikes in a number of words that are tied to current events, but have nothing to do with politics. For example, he says, "paparazzi" had a trend spike after Princess Diana was killed in a car crash while trying to escape photographers in 1997. He also recalls that Merriam-Webster's first tweet related to dictionary search data was "pandemic" in May of 2009 because the country was in the midst of the swine flu outbreak.

However, although Merriam-Webster may not be acting in an explicitly political capacity in its tweets, there is arguably something political even about clearly and accurately defining words under the Trump administration. As Maria Konnikova wrote this year in Politico, just ahead of Trump's inauguration:

The sheer frequency, spontaneity and seeming irrelevance of his [Trump's] lies have no precedent. Nixon, Reagan and Clinton were protecting their reputations; Trump seems to lie for the pure joy of it. A whopping 70 percent of Trump’s statements that PolitiFact checked during the campaign were false, while only 4 percent were completely true, and 11 percent mostly true.

Not for nothing did the New York Times released a new advertisement campaign just a month after Trump was inaugurated: "The truth is more important now than ever."

There is a sense that under the Trump administration, even words are not always held to accurate, objective meaning. Thus, defining them oddly becomes it's own political act, even if that's not necessarily Merriam-Webster's intention.

"Our job is to tell the truth about language. We are there to serve as an objective, neutral reference about language," Sokolowski insists.

While politicians are often criticized for being all talk and no action, Sokolowski actually thinks the value of the words get short shrift.

However, he does sense that recently there is extra interest in people caring about words and their meanings, even though he doesn't credit it to Trump. "That's one reason I think people have responded to us lately. They really care about the way language is used," he says. "They really care about if United is using 'volunteer' correctly or whether 'complicit' can be used to mean something positive or something malign."

To Sokolowski, interest in the meaning of words is heartening "because sometimes words is all we have" — and that's not a bad thing. While politicians are often criticized for being all talk and no action, Sokolowski actually thinks the value of the words get short shrift.

"Sometimes, in politics, you'll see politicians criticize language. 'Oh, he's got great rhetoric but it's just words.' And we realize politics really is often just words — the words of Churchill, the words of Kennedy, the words of Reagan, all inspiration for generations," Sokolowski says. "I think in this particular political moment, people are turning to the dictionary, but what they are telling us, if we can interpret anything at all, is simply that words matter."