Books

This New Novel Is A Feminist Retelling Of The Story Of The First Witch In Literature

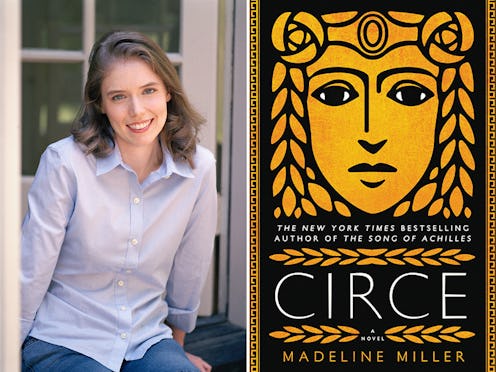

You might remember Circe as the beautiful enchantress from The Odyssey, famed for turning men into pigs. Or perhaps you only know her as a vague figure from hazy Greek antiquity, or as the namesake of the Game of Thrones character. But there is more to Circe than punishing men with potions and porcine charms. She is, after all, the very first witch in Western Literature. And now, at long last, Madeline Miller has woven her own spell to take Circe from a cameo in Odysseus's story to a formidable heroine in her own right.

Circe, Miller's newest novel, is a stunning epic of a book. Readers follow the goddess Circe from her youth in her parents' immortal halls to her exile on the island of Aiaia. Along the way, readers meet the sea monster Scylla and the infamous Minotaur, the hero Jason and his witch-wife Medea, the gods of Olympus and, of course, the star of The Odyssey himself. Miller conjures all these myths and legends in their full, lyrical splendor, and spins them into a page-turner that is wholly original.

This isn't her first foray into Homeric heroes, either — Miller's first novel, The Song of Achilles, is a bestselling re-imagining of The Iliad.

But in some ways, Miller feels that Circe has always been at the back of her mind, waiting to be written.

"I think my relationship to Circe goes back, actually, to reading The Odyssey in 8th Grade," Miller tells Bustle. "My mom had read me pieces as bedtime stories, of both The Iliad and The Odyssey, but I have no memory of Circe from that. This is my first memory of Circe."

Circe by Madeline Miller, $16, Amazon

Eighth grade Miller was thrilled to be reading this mythology on her own for the first time. "I was making notes in the margins, you know, I was so excited. I felt like I was a real scholar, approaching the text," she says. She was especially excited to get to Circe's chapter. "Here’s Odysseus, he lands on Circe’s island, he’s exhausted, he’s grieving, they’ve lost all the ships but one. And he sends his crew up to Circe’s house. She comes out and she’s this beautiful, powerful goddess. She lures them inside, she turns them into pigs, and now Odysseus has to go rescue them."

"I was just on the edge of my seat," says Miller. "I thought, there are so few female characters like this in Greek Mythology, who are really powerful, but not like, powerful with six heads who eat people." Circe was powerful because she was clever. She was skilled in witchcraft. And Miller wanted to see this battle of wits between the brilliant Odysseus and Circe, his equal when it comes to diabolical tricks and mental gymnastics.

"I thought, there are so few female characters like this in Greek Mythology, who are really powerful, but not like, powerful with six heads who eat people."

But when Miller got to the scene between them... it wasn't quite the showstopper she had hoped for. "Odysseus comes to her house, and he’s been equipped by Hermes with the magical herbs that make him immune to her spells. And she tries to cast her spell, it doesn’t work, and he pulls out his sword, and she immediately screams, falls to her knees, begs for mercy, and, you know, offers to take him into her bed," says Miller. "And as a 13-year-old, I just had this sense of profound disappointment. I remember throwing the book across the room." For young Miller, as a devout book-lover, that wasn't an action she took lightly.

"As a 13-year-old, I just had this sense of profound disappointment. I remember throwing the book across the room."

"It just felt like such a let down," says Miller. "It felt that she was this interesting, mysterious character who had all this power and agency, and then all of a sudden it was just like she had to roll over and yield to the male heroic narrative. She was just an obstacle to be vanquished in the male hero’s journey."

Out of this profound disappointment, though, came the first seed of what would become Circe. "What would the story look like if she was the center, and everything orbited around her, as opposed to her being forced to orbit around Odysseus?"

Miller came across Circe once again in college, where she studied classics. This time, she was still disappointed to see Circe shriek and submit to Odysseus's blade so quickly ("and could the sword be any more phallic?" she adds), but she also noticed more nuance in Circe's character this time around.

"Circe actually has gotten a very bad reputation," says Miller. People remember the pigs and the trickery, but they seem to forget that Circe actually helps Odysseus and his crew. "She keeps him on her island for a year, sort of helping Odysseus and his men get back on their feet," says Miller. "They’re emotionally exhausted, they’re physically exhausted. And then, Odysseus doesn’t even really want to leave. His men have to come to him and say, 'It’s time to go.' And so he goes to Circe and says, 'I’m ready to leave,' and she says, ‘Sure, I’m not holding you here.'” Circe doesn't imprison him. Instead, she gives him advice on how to talk to the spirits of the underworld, and how to get past the monsters that still lie ahead.

"All of that comes from her knowledge and wisdom. So that was really interesting, that she has such duality, and complexity, as a character. Both the benevolence and the menace, which is, again, very unusual for Ancient Greek female characters," says Miller. "I mean, sometimes you see that with characters like Athena or Artemis, but for the lesser goddesses, usually the characters are much more black and white. You have Medea and Clytemnestra who are the bloody villains, who get punished by the end, and then you have the sort of tragic saints on the other end."

"So that was really interesting, that she has such duality, and complexity, as a character. Both the benevolence and the menace, which is, again, very unusual for Ancient Greek female characters."

"But she was both," says Miller. "And so I really was drawn to that. And of course, she’s the first witch in Western Literature." That appealed to Miller too, that Circe's power didn't come from her divinity or her godly parentage, but from her knowledge and affinity with plants and animals. "Her power is something that she has invented herself."

That is the Circe of Circe: a woman who has invented herself. She's more than the Circe of Homer, and Miller was careful to limit the influence of The Odyssey in her text. "I wanted to keep Odysseus to only two plus chapters chapters of the book. That is exactly how much Circe is in The Odyssey," she says. "And you know, my point was, just as she is a cameo in his story, he is a cameo in hers. He’s important, as she is important, but there’s so much more to her life than that. So it was really important for me to keep the focus on her whole arc, as a female character, her whole life, you know, to give her her own epic."

She pulled from other myths about Circe, from Ovid and from The Telegony, a lost Greek epic about Circe and Odysseus's son, Telegonus. Nearly every major plot point in Miller's book, from Circe's mortal-sounding voice to the birth of her son, comes straight from the mythology. But Miller found herself pushing back against the myths more than she had with The Song of Achilles, trying to peel away the layer of male storytelling that has warped Circe into a two-dimensional, man-hating witch.

"I love Ovid, he’s a brilliant poet, but his treatment of Circe is just that she’s this angry, vengeful, lovelorn, kind of malignant witch, who’s constantly falling in love with guys who are just not that into her," says Miller. "It’s a very shallow and sexist portrayal, honestly."

With The Telegony, too, she remixed a few plot points that felt tacked on or too fairy tale-ish, like when Circe and Odysseus's son Telegonus marries Odysseus's widow, Penelope. "I generally feel like 16-year-olds should not marry 50-year-olds, whether it’s a man or a woman," Miller adds.

After all, Miller found that being wholly accurate to the male-authored mythology was not quite as important as staying true to Circe's character. "What’s important is to tell this character’s emotional arc," she says. "That emotional arc I saw as moving away from divinity, and towards mortality. The major theme of The Odyssey, for Odysseus, is a longing for home. He wants nostos, he wants homecoming. And I wanted that to be a similar animating theme for this novel, that Circe spends a lot of her time longing for home except, unlike Odysseus, she doesn’t know what that home is. Or where it is. So she not only has to find it, she has to make it herself."

Without spoiling the end of Miller's novel, that's precisely what Circe does.

Her story of longing and searching for home is, of course, timeless. But reading Circe today, the struggle of a powerful witch living in a world of men is also very pointedly relevant.

"...Circe spends a lot of her time longing for home except, unlike Odysseus, she doesn’t know what that home is. Or where it is. So she not only has to find it, she has to make it herself."

Circe is the first literary witch, says Miller, in part because she has a wand and familiars and great skill with potions. "But I think the thing that makes her a true witch is that she’s an embodiment of male anxiety about female power," says Miller. "That’s really what witches are. Witches are women who have more power than society says they should. Those are the women who get called witches. And they can be beautiful and alluring like Circe, that’s definitely one of the types. They can also be hideous. But in all cases, they have more power than they should, according to society. And what’s amazing is how strongly this anxiety about female power is still with us. I can’t believe that modern day female politicians are called witches. Still!"

"Witches are women who have more power than society says they should."

Fear of witches is still very much with us in the 21st Century. "Hillary Clinton, there were a ton of memes of her as the Wicked Witch of the West being melted," says Miller. "They’re all over the internet. It’s a real rabbit hole. So, it’s kind of shocking that we’re still slinging that word around. But I think it has stayed with us because society fears female power."

And Circe certainly has power. In a world that still fears women who speak out of turn, or live alone on their islands, or dare to have more power than men, Circe is the beautifully-penned love-letter to witchy women that we need more than ever.