Books

'Freedom In Congo Square' & A Little-Know Story

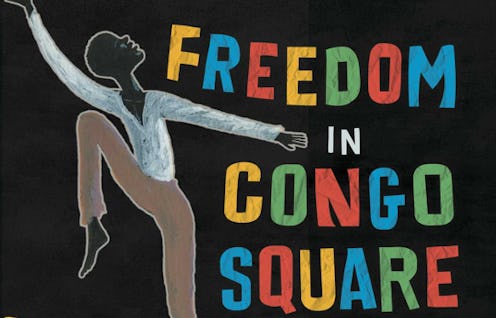

From the Million Man March to Occupy Wall Street “the right of the people peaceably to assemble” is a First Amendment protection that Americans have long been well-versed in — and it’s a right that may become even more essential in this shifting political climate. The right to peaceably assemble, and the power of gathering together over shared values and traditions, is also what lies at the heart of new children’s book Freedom in Congo Square. Published by Little Bee Books last year, Freedom in Congo Square is a poetic, nonfiction picture book written by Carole Boston Weatherford and illustrated by R. Gregory Christie, and it’s educating young readers about a little-known story in slave history.

Freedom in Congo Square takes readers back to 18th century Louisiana, where a New Orleans city law granted African slaves Sundays off, and where an 1817 law designated Congo Square — a public square located in what is now the Treme neighborhood of New Orleans — the only place where slaves were permitted to publicly gather. And publicly gather they did, by the hundreds: filling Congo Square with dancing and singing, and playing music that fused the sounds of traditional African instruments with North American ones. It is this musical collaboration that first drew award-winning nonfiction children’s book author Carole Boston Weatherford to the topic of Congo Square in the first place. “I was drawn to this subject because I love jazz. Without Congo Square to keep African rhythms and traditions alive, New Orleans might not have become the birthplace of jazz.”

The musicality of Congo Square is celebrated in the text of Freedom in Congo Square as well. The story is both rhythmic and rhyming, and takes young readers through six days in a slave’s daily life before the much-anticipated Sunday gathering in Congo Square — the glimmer of hope and freedom that came at the end of an oppressive and labor-filled week. “The main challenge was to make slavery understandable for children,” says Weatherford. “I did so by framing the relentless labor and inhumanity with a day of the week [and a] countdown rhyme. The book underscores the persistence and preservation of African cultural traditions, and attests to the spirit and endurance of African descendants.”

The text of Freedom in Congo Square is accompanied by beautiful, evocative illustrations. Coretta Scott King Award-winning illustrator R. Gregory Christie says he was inspired by the unique history of slavery in Louisiana, as compared to the stories of other slave regions in the United States. “Overall I was inspired to tell a story that would hopefully make people look at the state and people of Louisiana as a very unique culture. It’s an American gem to me and I wanted to convey that sentiment to my audience,” says Christie.

“I feel that it's important to package books like Freedom in Congo Square as American history,” says Christie.

Both Weatherford and Christie are aware of the unique responsibility they have as storytellers and as children's book creators. “We are molding the minds of people who do not have many life experiences. It's important to be hopeful and positive with the information you relay, but also to tell the truth as you know it from your own life experiences,” says Christie.

“I believe it's an obligation for each generation to leave tools behind for future generations. It's important not to let our schools’ history lessons become too stale,” Christie says. “Many cultures make up America; they've all contributed to the infrastructure, habits, and overall culture of the country. At the end of the day, the root of this story begins with enslavement, something that still goes on today in other parts of the world. I want people to read the book and empathize with the dynamics it speaks about, and to see that period in history as a shameful time, when, if the people had dug deeper, they could have come up with a better solution than harsh enslavement.”

And then there’s the power of gathering itself. “I feel that it's human nature to socialize in groups, especially during new or stressful situations. It's something most people are wired to do. There is strength in numbers. The less people organize, and the less they see an obligation towards another person as a human, the easier it is to see war, racism, slavery, and prejudice as normal. Once people are divided by force or fear, I feel they are on a path to lose self-reliance, or even their humanity. I can only imagine the sun-up-to-sun-down drudgery of the enslaved people mentioned in Freedom in Congo Square. I truly hope that being able to meet once a week was some kind of hope during such a sense of loss, and that secretly the slaves were able to disguise escape in the form of a dance.”

Freedom in Congo Square fared well with reviewers in 2016. Among other accolades, the children’s picture book was recognized as a New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book, a Washington Post Best Nonfiction Book, a Kirkus Best Picture Book, and a School Library Journal Best Nonfiction Book. “I have already seen the book making an impact on society's knowledge of that region and history,” Christie says. “Hopefully, with more exposure, it will spark an interest in the general, and inspire libraries and schools to use it in their curriculum.”

"As a children's book author, I mine the past for family stories, fading traditions and forgotten struggles. Yet, I write for the future," says Weatherford.

“More Americans need to know about this sacred ground,” Weatherford believes. “I hope that Freedom in Congo Square increases awareness. As a children's book author, I mine the past for family stories, fading traditions and forgotten struggles. Yet, I write for the future.”

Freedom in Congo Square by Carole Boston Weatherford & R. Gregory Christie, $13, Amazon