News

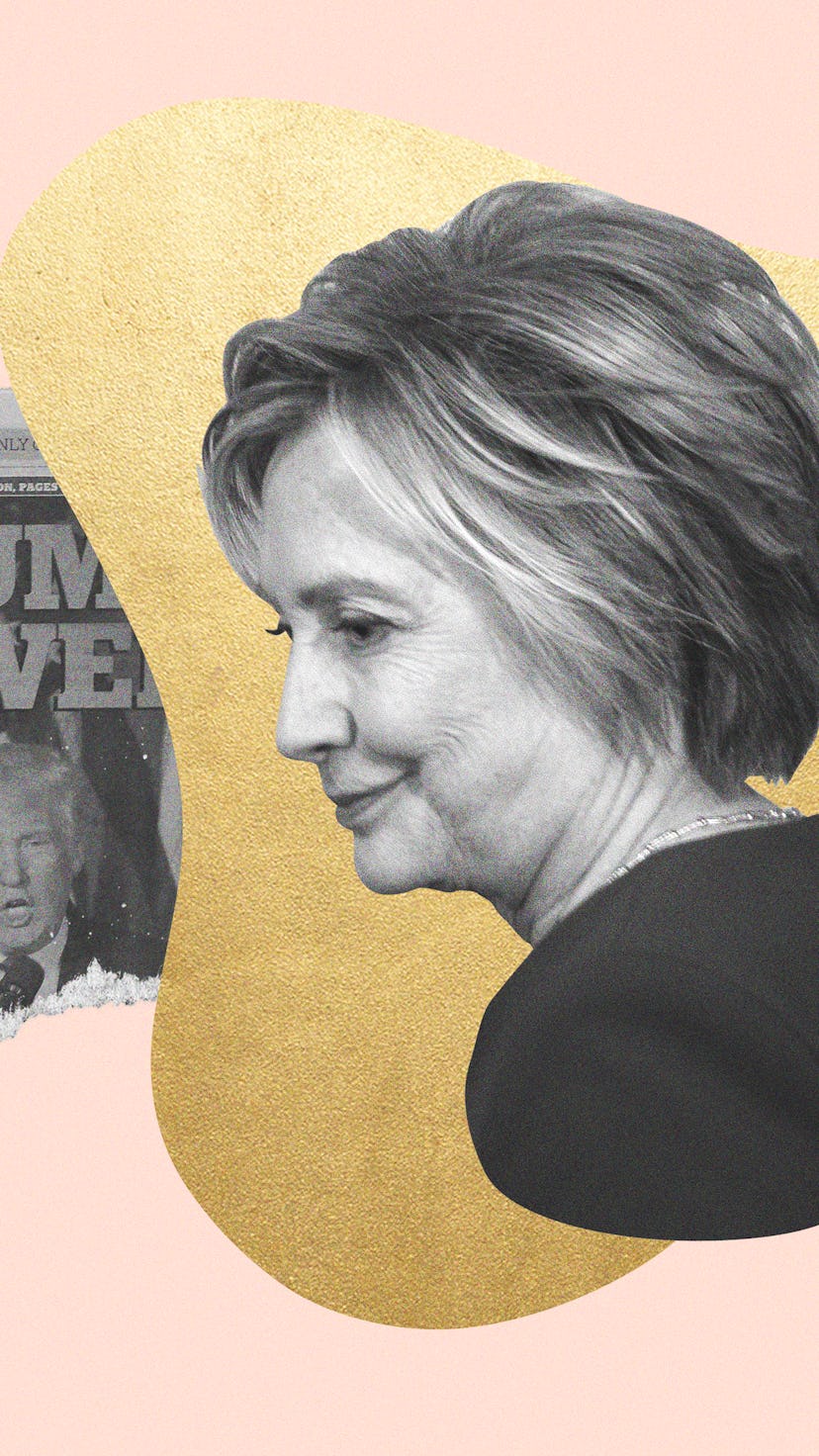

Checking In One Year Later With The Women Who Almost Got Hillary Clinton Elected

On Nov. 8, 2016, I was on the hook to file several election-related pieces, and had made the process easier for myself by pre-writing four different versions of “What does the first female president mean for America?” It was 3 a.m. when I woke up in Nairobi, Kenya, where I was living that year, and as I opened the New York Times app and saw an electoral map that looked awfully red, I thought that I might still be dreaming.

Not that it really mattered — states that are physically large often go Republican, so a red South and middle didn’t seem so alarming. But… was that Florida? Pennsylvania? Wisconsin? Maybe my brain just wasn’t working yet; it was still dark outside, and I had barely slept the night before. I got up and made coffee, and by 5:30 a.m. — 10:30 p.m. on the east coast of the United States — I was planted on my couch, stunned and convinced that, maybe, because I was thousands of miles away without a TV to blare CNN on, I was just reading the results all wrong. Then, one of the four editors for whom I had filed a “Hillary Wins” piece sent me a message: “Hate to say this, but it’s time to start thinking about Plan B.”

I got to work. I don’t remember what I wrote for four — maybe five? — different outlets, and I don’t have the stomach to go back and re-read those words. By 6 p.m., the new pieces were filed and my tap was dry; I went to yoga and, finally, cried on the floor in pigeon pose. When I got back to my apartment, I hugged an American neighbor who was just arriving home from work. “I cried so hard in my Uber that I had to apologize to the driver,” she told me that evening. “Don’t worry,” he said, before telling her he had seen lots of Americans having meltdowns, “there have been white girls crying in this car all day.”

"And that was the moment where I was like, oh, we’re gonna lose. We are going to lose."

It wasn’t supposed to go down this way.

Hours earlier, the streets of New York City were buzzing. Hillary Clinton’s campaign team was setting up what was expected to be a victory party at the Jacob Javits Center on Manhattan’s west side. Donald Trump’s camp was preparing for an uncertain evening at the Hilton Hotel, just a brisk walk from Trump Tower. And Aminatou Sow, a Clinton supporter and co-host of the popular feminist podcast Call Your Girlfriend was feeling festive and ready to vote.

“I was wearing this very loud floral pantsuit, as one does,” Sow tells me. “There were a lot of women wearing pantsuits, a lot of women in suffragette white. The energy was through the roof.”

Jess McIntosh, director of communications outreach for the Clinton campaign, says that she wore her mother’s and her grandmother’s rings to cast her ballot for her boss, who she thought would be the first female president, and then joined other Clinton campaign staffers at the Javits Center.

As Amanda Litman, the Clinton campaign’s email director explains: “We were all hyped; we thought we were going to win.” But, as the evening progressed and Clinton lost Florida and Ohio, the mood shifted.

McIntosh, who suspected the game was up when Florida went for Trump, took a break to go to the bathroom and “two women were just sobbing on each other.” Both were Latina employees of the Javits Center. “[This was] at 8:30 p.m., so early, when people were still holding out hope. So that was my like, 'yeah, this is super-real' moment. This is what’s gonna happen.”

Back in the campaign staff pen, a man from the communications department came to give Litman’s team a pep talk — the Midwestern firewall of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan was all they needed. “And as he said that, he sat down, and I remember that every TV channel we were watching at the time called Wisconsin for Trump,” Litman says. “And that was the moment where I was like, oh, we’re gonna lose. We are going to lose.”

“It would have felt like such a personal victory.”

In Brooklyn, Sow, who volunteered for the campaign, was still wearing her pantsuit. “It feels like it was the beginning of a nightmare,” she says. “I don’t remember much except shock and sadness.” It also felt personal. As a girl in Lagos, Nigeria, Sow had watched on TV then-First-Lady Clinton’s speech at the 1995 Beijing Conference on Women’s Rights, when she made her now-famous “Women’s rights are human rights” speech. “It was such a profoundly transformative experience for me as this young African girl,” Sow explains. “One, seeing a gathering of women and thinking it’s amazing and badass, and also watching that with my mom, who is an African woman who went through a lot of things that were relevantly discussed at the conference, and that opening up a line of communication for us in talking about women issues.”

Litman also felt an intimate connection with Clinton. “She reads mysteries, she does yoga, she has her dogs that she likes to walk around with, she reads trashy books, and watches HGTV. I see myself reflected in this woman,” Litman says.

Partly because she was so easy to identify with — and partly because the stakes were so high — Clinton’s loss was all the more devastating.

“[Her winning] would have felt like such a f-ck you to every person who has ever tried to quiet me, or said sit down, shut up, interrupted me in a meeting, [said] you’re too much,” Litman says. “It would have felt like such a personal victory.” Instead, Litman took a cab home and had to pull over on the side of the road to vomit.

By the time McIntosh, the director of communications outreach, left the Javits Center, darkness had long since fallen. She walked into her apartment to see the celebratory table setting her boyfriend had set out for her, left untouched. “He’d drunk himself under the covers and left all the champagne out,” she says. “I had to cry in the bathroom, at which point he, of course, woke up and we drank the champagne on the floor. And that really set the tone for the next few weeks.”

Across the country, similar scenes were taking place. Libby Chamberlain, who started the Pantsuit Nation Facebook group that quickly exploded into millions of members, spent Election Day in busy pre-celebration mode: She dressed her 3-year-old daughter in a pantsuit and dropped her off at school before bringing her 1-year-old son to vote with her in their rural Maine town. She then spent the afternoon working and, along with 150 volunteer moderators, fielding some 140,000 Facebook submissions to the group. There were photos of old ladies and little girls, women in hijabs and women with buzz cuts, women in wheelchairs and women toting infants (a few enthusiastic men were in the mix, too).

Over in Nairobi, I scanned through those posts, choking up and, for the first time since I had moved, wishing I were in the United States.

When Chamberlain arrived home from work, she went into her office to pen a community post on Clinton’s win. Her husband, who was watching the results on TV, told her to come watch what was happening. “I walked away from my computer... it’s rare for me to not be on my computer or my phone for more than a few minutes at a time,” she says. “And I felt like I just deflated into the couch.”

It’s doubtful that any woman who supported Clinton slept well that evening.

"I don’t know what this country, this city, this place is anymore."

On the morning of November 9, 2016, Clinton gave her concession speech in what Litman describes as “the worst hotel ballroom” she had ever been in.

“Everyone was crying except for Hillary,” she says. “Everyone.” Afterward, not knowing how else to spend her time, Litman went back to work — at Clinton headquarters. “What do you do? The only thing you’ve done for the past two years is work for a cause, and then that work fails, where do you go?”

“It was like we had a terrorist attack,” says Sow. “People on the train were crying. I saw complete strangers hug each other on the A train, and that shocked me to my core — hello New York City.”

For those who had worked for the Clinton campaign, or volunteered their time, or had fully expected her to win (which most of us were guilty of), the days that followed were dark and full of denial and cognitive dissonance. “It definitely didn’t feel real,” McIntosh says. “It was terrifying. It’s one of the worst feelings. Having experienced death and divorce, that’s up there.” Much of time, Sow says, “It still doesn’t feel real… It’s been a year and it has not set in.”

It was also a moment of reckoning that Trump supporters weren’t on the margins of American society; they were significant enough in numbers to win a presidential contest. None of the women I spoke with were surprised that racists and sexists exist in the United States, but their numbers were chastening, and their shamelessness distressing.

“There was nothing about the election that was like, wow, I didn’t realize there were so many racist and sexist people,” Zerlina Maxwell, a communications staffer in the Clinton campaign tells me. But, she says, “I was hopeful that it wasn’t this way, or that there were fewer people who felt that way and we would have still been able to win, which would have been a really monumental moment.”

"That was the first time that it dawned on me that these people were actually everywhere."

While recounting the following story, Litman pauses, concerned she might start to cry. “I will never forget that feeling of walking through Times Square after leaving Javits,” she says. “Every guy I saw who was wearing a baseball hat, particularly a red one, [I was] thinking, I don’t know if you’re safe, I don’t know who to trust, I don’t know what this country, this city, this place is anymore. What kind of country picks someone like him to be president?”

Days after the election, Sow was dining at a hip pizza restaurant in Brooklyn when she heard a couple at the table next to her boasting about voting for Trump. “I got so upset, I had to leave the restaurant,” she says. “That was the first time that it dawned on me that these people were actually everywhere. They weren’t my friends’ parents in Texas, they were literally living in Brooklyn, eating liberal hipster pizza with me.”

For McIntosh, it was her dad. She knew he was a bit right-of-center and was probably supporting Trump, but they aren’t close and rarely discussed politics. When they had their annual Christmas call, the conversation turned to the president. “It turns out that not only was he a Trump supporter, he was a Pizzagate conspiracy theorist, Breitbart down the rabbit hole,” she says, referring to the debunked right-wing conspiracy theory that Comet Pizza in Washington, D.C. is a hub for child sex trafficking and murder, all enabled by the Clintons and their cronies. “I said, ‘Do you think I’m involved in the baby eating?’ And he goes, ‘I hope not.’ That was more or less the end of that conversation.”

The post-election fallout also revealed divisions on the left, which has made everyone concerned for their chances come 2018 and 2020. “What surprised me is the lack of reflection by people even in the Democratic Party that may not have supported Hillary in the primary, and I’m talking specifically about the Bernie folks,” Maxwell says. “The election was so close — everything mattered. But I would hope my fellow progressives would reflect a bit that voting for a third party candidate in a race that was so critically important for marginalized people — that you pretend to care about or, or portend to care about — that this was not the time to do a protest vote, or the time to be like, ‘I am progressive on principle so now I am going to ensure that Donald Trump wins so that marginalized people have to live in hell for at least the next four years.’ That’s not progressive.”

"The next time a woman runs on the ticket, her fiercest critics will probably come from the left.”

Peter Daou, who worked for the Clinton campaign in 2008 and remains a supporter, notes that “on neither the left nor from the mainstream media, or from the Republican side as well, has there been any taking of responsibility. The mantra has been, it’s Hillary Clinton’s fault, blame her for everything, move forward, and stop talking about the past.”

“A lot of the conversations happening around Liz Warren and Kamala Harris and even Kirsten Gillibrand lead me to believe that the next time a woman runs on the ticket, her fiercest critics will probably come from the left,” says Sow. “One of the big fallouts from the election has been that a lot of people in Democratic circles and a lot of circles are decrying what they call identity politics. To think that people of color and other marginalized populations are the ones that are shouldering the blame for bringing down the Democratic Party is something that is so insulting and ludicrous. Those are the ideals that we should be doubling down on.”

"The majority of Americans know something is not right."

Since the inauguration of Donald Trump, there has been some healing, and more importantly, some coalition building. After taking a few months to lick their wounds, many of the women and men who supported Hillary Clinton have channeled their pain into action. First, there was the Women’s March in January, which drew over a million people to Washington, D.C., and inspired more than five million people to rally in other parts of the U.S. Watching the march, Litman says, “was a really bittersweet moment. I was surprised at how few campaign people went to it, engaged with it, participated in it. I think for a lot of us it was like, this is an incredible movement, and where were you? Where was this passion for women and our values four months ago, five months ago?”

But then, when Donald Trump signed an executive order limiting the ability of people from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States, thousands of protesters descended on American airports. “The Women’s March was great and it made me feel very good, but the airport protests were the first moment that I was like, maybe we’ve got this,” McIntosh says. “[The protesters] weren’t all Muslims. [They were] the nice white ladies who everybody wondered whether they were going to show up again after the Women’s March. And they did, when people needed them.”

The Resistance may not be one organized entity, but it is a force many Americans have rallied around with a determined single-mindedness. “If you have a fever or a virus, your entire focus is, ‘How do I get this out of my system?’” Daou says. “The word 'resistance': You are trying to resist something that has inundated the body politic, and the majority of Americans know something is not right.” That’s heartening, he says, but, “November 8th was the time we could have stopped this from happening. And we are now in a different reality. I’m not sure people are accepting that.”

Though still shell-shocked by the election results, Chamberlain decided to keep Pantsuit Nation going, and shifted the group to focus on civic engagement to get women involved in politics in their own communities. Maxwell joined SiriusXM, amplifying her voice in the anti-Trump resistance. Many women find themselves focusing more closely on their own communities and prioritizing their own values. For Sow, that has meant taking stock of her personal network.

“One thing that I think happened definitely for me in the election was looking around at the white women in my life and feeling an insane sense of distrust, like, well, this is everything that the feminist movement has been talking about for years and this is where intersectionality is so crucial,” she says. “The election really laid that bare.”

“What surprised me was the non-college-educated white women who voted for Trump."

That 53 percent of white women voted for Trump was disappointing to McIntosh as well, but not surprising — white women, especially married white women, have been a loyal Republican voting bloc for years, and slightly fewer voted for Trump than cast their ballots for McCain in 2008. “For once we aren’t talking about women as a monolithic voting block, probably because everyone wants to accuse Hillary of losing the women’s vote, so we have to break it down to talk about it,” McIntosh says, adding that 51 percent of college-educated white women voted for Clinton — more than voted for Obama. “What surprised me was the non-college-educated white women who voted for Trump."

What shook her, she says, was how women who voted for Trump justified themselves. “All those focus groups that you saw afterward, where people were like, ‘Why did you do that?’ even after the Access Hollywood tape, and they all said, ‘Because that’s just how men behave. That’s not weird and we can’t disqualify him for that because then we’re disqualifying all men.’ Obviously that’s not how all men behave, but in their world, it is.”

Of course, plenty of liberal men harass and assault women too — just look at Harvey Weinstein — but the degree to which female Trump voters seemed to believe Trump's chauvinism was normal and acceptable, McIntosh says, was a heartbreaking realization that engendered at least a modicum of sympathy.

"If Trump can win, why shouldn’t I run?"

For many Clinton voters, the election made clear that political passivity was no longer an option. Those whose careers have been focused on politics are responding: They’ve spent much of the past year trying to change the electoral map by getting more progressives, and especially more women and people of color, into positions of power. Litman, who was doing “a lot of sleeping and drinking and crying and trying to re-find my life again,” began receiving messages from old friends and acquaintances saying they were thinking about running for office but didn’t know where to start.

Realizing there wasn’t an organization dedicated to helping young people enter politics, she decided to start one. “I worked to cope with it — the rage, and the fear, and the depression,” she says. “I worked because it was better than feeling my feelings. It was better than being sad.” Her organization Run For Something launched on Inauguration Day. “We were like, maybe we’ll have 100 people want to run in the first year. And in 10 months, we’ve had 11,000 young people around the country sign up to say they want to run, another 50,000 to say they want to help.” Young women have been a particularly strong force.

“The election of Trump, pardon my language, was a f-ck you to women across the country,” Litman says. But young women are flipping the bird right back. “You would think they would say if the most qualified woman and qualified liberal candidate in history can’t do it, how can I do it? They’re flipping it: If Trump can win, why shouldn’t I run? If Trump can do this, that idiot, if he can pick Betsy DeVos as his Secretary of Education, who knows nothing about public education, then why shouldn’t I be on my school board? Why shouldn’t I run for city council?”

Twelve months after Donald Trump became our president, there are more women than ever in the political pipeline. McIntosh’s previous employer, EMILY’s List, an organization that supports pro-choice women running for office, typically gets a few hundred women contacting them about running every year. At the Women's March Convention in October 2017, they announced that over 20,000 women had contacted them about running since the election. “I think we might be fixing the [mentality of] ‘ew-politics, ew-elections, I hate campaigns, it doesn’t speak to me, it’s all gross,’” McIntosh says. “When people can start seeing themselves in candidates and seeing their own place in local elections, we might be actually able to make some progress.”

Still far away in Kenya, it's heartening for me to hear women who work in politics say they are feeling good about the future, mostly because I don't feel that way myself. The longer I am away, the less I want to go home. Every day, it seems, there are multiple stories that two years ago would have dominated headlines for weeks, but Americans are so burned out on news and scandal that very little breaks through — and so ensconced in their own views that they brush aside whatever doesn't confirm their existing opinions. That many Americans still support Trump, and that the Republican Party so easily abets him, has me increasingly pessimistic.

"There has been something really comforting about her presence still, and the fact that she has refused to go away."

Back in New York, Aminatou Sow says she still feels a bit amiss as well, but she does have hope. She sees the same issues that kept Clinton out of office – disdain for female ambition, misogyny on the right and the left – still operating with full force in American politics. “The fact that we’re all shocked [one year later] speaks so much to human resiliency, and to the fact that things are really bad. But, there are people who are genuinely working to make them not as bad,” she said.

One of the people Sow looks to on that front is Clinton. “There has been something really comforting about her presence still, and the fact that she has refused to go away even though people have been calling for her to. I don’t know if that means we’re going to be OK, in fact that’s not the significance that I’d give it, but it has really inspired me to not wallow in this moment and to try to change things in the ways that I can.”

To mark the election anniversary, “I will keep doing what I am doing,” Sow said. “Which is – not ignoring, but trying not to dwell on it. It’s not dramatic to say that in my short lifetime this is a thing that has really radicalized me, this election loss. It’s made me rethink where I spend my energy and who my actual community is and who are people I can trust and people [with whom] I can coalition-build and people who really want to propel the world into a better place.” Sow, like many feminist progressives, is now doubling down on efforts to get black women elected to office.

"Black women are the future of the Democratic Party."

That urgency and optimism is echoed in many feminist circles. In fact, many feminists believe that the only way the Democratic base will see themselves in candidates is if those candidates are as diverse as Democratic voters are. Twelve months since Hillary Clinton lost, many Clinton-camp progressives are hoping that the rest of the nation will see what they say their candidate recognized: that black women are the most loyal Democratic voters in the country, and that the party has been neglecting them in a post-election frenzy to attract Trump-voting working-class white men.

“Black women are the future of the Democratic Party, and until the Democratic Party understands that, and until the more left-wing of the party understands that we need to center black women in the work we’re doing, we are going to be doing it all wrong,” Maxwell says. But she doesn’t have to look much further than her former employer, who had the most diverse campaign staff in American history, to feel optimistic about where we’re headed.

“[Hillary Clinton] hired some of the future leaders of the country, probably a future president,” says Maxwell. “One of the black women I worked with might be the president one day.”