Life

Here's What It Actually Takes To Become An Abortion-Providing Doctor

When Dr. Elise Boos was a third-year medical resident, she would drive five hours north throughout the year to a clinic in Shreveport, Louisiana — one of the three abortion clinics in the state — to learn how to provide first and second trimester abortions. She and the other residents had to stay at a nearby hotel for two weeks at a time. Boos, who is now a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, says the rotation reinforced the stigma of the procedure for her, "because you had to leave town in order to get this training," she says. "It was hard to imagine how you could do that work in the South and still be a member of the medical community."

Prior to her rotation in the clinic, Boos says she hadn't thought much about abortion access. She grew up in a Catholic family in New Orleans where abortion was taboo. But during her rotation in the Shreveport clinic, she says she was struck by how many barriers the patients faced. She met people who had traveled hundreds of miles, some from other states, for abortion care. In Louisiana, patients must wait 24 hours between their first appointment and an abortion procedure. Some of the patients Boos saw had stayed in hotels, while others slept in their cars. Most of them were paying $600-$800 for the procedure.

Boos says that seeing these barriers made her want to become an abortion provider, no matter what it took. "We all need access to this care," she tells Bustle. "And I was determined to get the training."

Becoming a physician who provides abortions in the United States has never been easy. One study found that only 32% of medical schools surveyed offered at least one abortion-related lecture during clinical years, and half said they offer a fourth-year elective in family planning and abortion. But the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists wrote that students are often required to seek out abortion experience at off-site facilities. That means "students without a special interest in abortion may not have an opportunity to observe clinical abortion care," ACOG noted.

Dr. Gabrielle Goodrick, owner of Camelback Family Planning, an independent abortion clinic in Arizona, tells Bustle that when she completed her residency in the '90s, abortion was not integrated in any form. She chose to do an outpatient gynecology rotation in the surgical clinic of a local Planned Parenthood. After that, she completed additional training with her mentor after hours.

"That was the only way I could get training," she says. "Any abortion training, you have to initiate on your own."

Things have improved over the last 25 years, in part thanks to Medical Students for Choice (MSFC), a nonprofit founded in 1993 that advocates for better clinical exposure to abortion and reproductive health care for medical students. The organization now has more than 220 chapters in 23 countries. MSFC and programs like the Ryan Residency, which helps establish family planning curricula for OB/GYN residencies, have helped make abortion training more accessible. There's also the University of California, San Francisco's Fellowship in Family Planning, which provides two years of specialized training in abortion and contraception after a physician completes their residency. (Boos just finished the fellowship.) Some states also allow nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certified nurse midwives to provide abortions, though many only allow them to provide medication abortions.

Though access to training has improved for medical students, Lois Backus, the executive director of MSFC, says that students at certain schools often have to be "stealthy" in seeking it out. She describes the medical education institution as "slow to change and resistant to controversy." She says students who are overt in their advocacy for better training or support for local abortion providers can face consequences. MSFC has had members who weren't placed in a residency program "because their deans described them as controversial people or people who didn't toe the line and play well with others," Backus says. "It's really important for a medical student within this larger conservative culture to be very cognizant of the damage [seeking out abortion training] can do to their futures."

Providing abortion services is unfortunately very different than practicing any other kind of medicine.

Once physicians have completed their residencies and any other training, they have to find a job as an abortion provider. The demand for abortion services most often goes unmet in states with more abortion restrictions and fewer providers. Those states are also the ones where physicians could face more harassment or even violence for providing abortions.

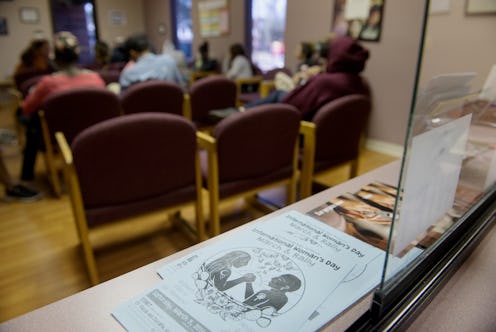

None of the providers Bustle spoke to say they are afraid of violence, but all say they think about it often or have taken precautions to protect themselves. Goodrick says that in 2009, after Arizona passed an omnibus measure that included multiple abortion restrictions, more providers disappeared. People started protesting outside of the clinic, so she had to increase security. "It just started to feel more not like a regular office," she says. The clinic has cameras, a secure front door, and a check-in window with glass that's 1-inch thick.

Harassment can also follow abortion providers to their homes. Tammi Kromenaker, the clinic director at Red River Women's Clinic in Fargo, North Dakota, says anti-choice advocates passed out leaflets in one of her physicians' neighborhoods in Minneapolis. The leaflets said, "Did you know your neighbor provides abortions?" Luckily, the outcome was positive. "She got flowers from some of her neighbors," Kromenaker says, and others invited her over for dinner. But the outcome could have been very different. After the 2015 release of the discredited, heavily doctored videos intended to disparage Planned Parenthood, there was a spike in harassment of abortion providers, HuffPost reported. Many were picketed at their homes and some received death threats.

Many physicians who provide abortions live in cities in part because of the threat of violence, but Boos says some also have private practice offices that they work out of for the rest of their week. Then, abortion clinics in states that are hostile to abortion fly their providers in one or two days a week.

Kromenaker says she could name almost all of the providers in the Midwest, and most of them live near Minneapolis, Minnesota. The three physicians who work at Red River provide abortions on Wednesdays and they all also provide abortions at other clinics.

"Our doctors travel in from out of state, and there's an additional cost that goes with that," she says. "But there's just not that many people in North Dakota. It's not like we're in a big urban area where we're struggling to keep up with the demand."

Providing abortion services is unfortunately very different than practicing any other kind of medicine. The stigma and alienation that Boos felt when she had to drive five hours to the Shreveport clinic during her rotation is evident in both the barriers to becoming a provider and in the obstacles providers face trying to get to their clinics and keep staff safe.

Boos says she would "absolutely" be willing to fly into a clinic farther from where she lives to provide abortions. She thinks about facing harassment a lot, but says it's a "price I'm willing to pay" in order to care for patients. "I think when you do acquire this skillset, you do take on a certain amount of responsibility," she says. As states work to restrict access to care, "You need to go where you're needed."

This article was originally published on