Books

'I'm The One Who Got Away' Is A Memoir Every Modern Love Fan Needs To Read

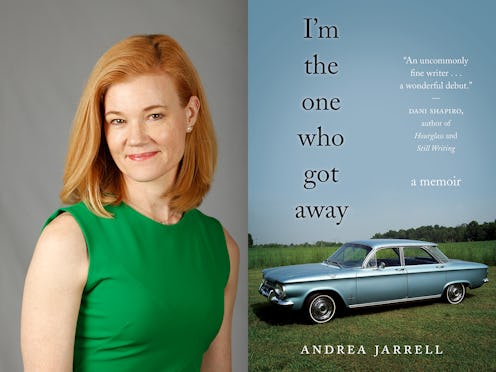

Beginning with a personal essay published in the New York Times in 2012, writer and debut memoirist Andrea Jarrell has walked (or rather, written) the path many hardworking writers aspire to: one leading from celebrated Modern Love column to published book. Inspired by the column A Measure of Desire — about a woman who compulsively imagines new wives for her husband — Jarrell’s recent memoir, I’m the One Who Got Away, bookends that original column by starting with the writer’s childhood escape from a violent but captivating father and ending with the story of Jarrell’s own marriage marked by alcoholism and healing.

Before her memoir’s publication on September 5 by the indie, female-focused publishing company She Writes Press, Jarrell connected with Bustle over her viral New York Times column and what it means to navigate your family’s intimate history on the page.

“I started writing this book a long time ago as a short story collection,” Jarrell tells Bustle. “But my stories were so autobiographical that at a certain point I began to explore them as creative nonfiction. The Modern Love essay began as a story about a woman who thinks her husband is too good for her, so she imagines better wives for him. This was something that I really did. That particular essay held most of the themes and tensions I wanted to write about in my book.”

I'm The One Who Got Away, $12, Amazon

Themes like relationships, the spaces girls and women occupy in the world, the internal lives of wives and mothers; tensions like the violence of desire, the parallels between being desired and being vulnerable — fill I’m the One Who Got Away. Jarrell’s Modern Love column, which interrogates so many of these, was something of a lighthouse for the writer throughout the process of completing her memoir.

“I found myself returning to it again and again to help me focus on the central questions I wanted my memoir to explore,” says Jarrell, of the column that went viral upon publication. “Questions about how desire and desirability can both empower and endanger girls and women; questions about making the choice to be happy and accepting that you don’t have to earn happiness — you don’t have to be “worthy” to allow yourself to be happy.”

In I’m the One Who Got Away, Jarrell’s mother embodies that dichotomy between empowered and endangered: an ambitious and academic woman, who nonetheless succumbs to the charms of a domineering man, ultimately finding herself a young, divorced, single mother on the run from a dangerous relationship. Jarrell’s description of the early days of her parents’ relationship and marriage — as overheard by Jarrell throughout her childhood, via family gatherings and gossip — is both relatable and chilling.

“Part of what I try to get at in the book is all the times I heard these stories indirectly,” she says. “I remember so many weekends when the women in my family — my mother, grandmother, aunts, and their friends — sat for hours talking. I was about 6-years-old through 9. They would forget that I was there or didn’t think I understood all that was being said. So, I absorbed these stories early.”

I ask what it was like for Jarrell to navigate the history of her parents before she was born — two people of a different generation, younger then than Jarrell and her own husband are now, and whose story Jarrell had to wind her way through before she was able to fully understand her own.

“This is where starting out as a fiction writer really helped me,” she says. “Because I began by exploring my parents’ story in fiction, I didn’t have to be so precious with them. In my fiction, they weren’t my parents; they were characters in a story. Both of them had told me so much about what they did and how they felt before I was born, so I had the reality but I also wasn’t trying to ‘remember’ what happened. I was allowing these people to exist separately from my experience of them. It was important to me that I wasn’t trying to own their story but to use it as a touch point to inform mine. Their relationship before I was born became a fable to me — a cautionary tale that informed my life and choices.”

There are certainly fable-like elements to Jarrell’s story. Her father, an abusive but charismatic actor who would come to both charm and torment her mother, enjoyed a relative degree of fame, running in the same circles as celebrities like Robert De Niro, Frank Sinatra, and Joe Pesci. But it’s also a fable that, as Jarrell writes in I’m the One Who Got Away, often led her to wish her mother had made other choices — had never met her father or had left him sooner, rejected his marriage proposal, chosen instead to finish college, and hadn’t become pregnant with Jarrell herself.

“As an adult now, with a husband and children, of course I am glad I was born and have had the life I’ve had,” Jarrell says. “But for a good chunk of my childhood I really wished I’d never been born — not because I was so unhappy — not at all. But because I was convinced if my mother hadn’t had me she could have started over, gone back to college, had more of the life she imagined for herself. I admired her so much and felt she had been cheated out of college and the kind of career she really wanted.”

But any regrets, Jarrell notes, were entirely her own. “I want to be really clear that my mother has always said I was the best thing that ever happened to her. She wouldn’t like readers thinking she regretted having me.”

Jarrell’s mother left her father when Jarrell was just a toddler — going as far as changing their last names, moving across the country, and frequently traveling the world. In many ways, it was a childhood that, under other circumstances, might have been another daughter’s dream: international travel, spontaneous adventure, the uninterrupted attentions of a spirited young mother. But, as Jarrell says, growing up she always knew that she and her mother were really in hiding from her father.

“As I got older and could handle more of the truth, my mother told me how frightening he had been and all that he had put her through,” Jarrell says. “Then when I finally met him I experienced a lot of it for myself.”

It’s a meeting that Jarrell describes in the memoir — one that surprised her and, in many ways, complicated the story-like image Jarrell had always had of her father.

“The big shocker about their [Jarrell’s parents’] relationship was when he came back into our lives,” she says. “He had always been the villain, but when he came back things weren’t so black and white. At first that was hard to accept. It wasn’t until I started exploring this material through my writing — from the vantage point of my recovery in Al-Anon and my own marriage — that I could understand their story better.”

Like many young people growing up separated from one or both of their biological parents, Jarrell describes an intense desire to know her father. In her memoir, during a moment shortly after her father has reentered her life, Jarrell writes of herself and her mother: I think we’d both been waiting all those years for him to find us. She describes a similar sentiment now.

“I’ve spoken to friends who have been adopted. They often talk of feeling like a piece of their internal puzzle fit into place when they met their birth parents. This was how it always was for me,” Jarrell explains. “I felt certain that one day I would meet this man. I had to know him. Growing up in a single-parent household during the sixties and seventies was a much bigger deal than it is now. I think most kids have something about them that makes them feel ‘different.’ Mine was not having a father who lived with me or even that I saw on weekends. The fact that I also saw this father on the occasional television show both heightened the drama of hiding from him and also intensified my longing to know him — even if most of what I knew about him was scary.”

The heart of Jarrell’s memoir, however, is not her relationship (or lack thereof) with her father, but rather her relationship with her mother — how she saw her mother as a child, how her understanding of her mother’s own struggles and desires evolved over time, and how Jarrell needed to both navigate and escape her mother’s story before she could understand her own.

“One of my most personally profound takeaways from writing the memoir is this: my mother has lived a more solitary life than I ever wanted to live but she is the one who taught me how to love,” says Jarrell. “If she had not loved me so well I wouldn’t have been able to forge the marriage I have. She taught me how to love and be loved; how to respect and nurture the dreams of your loved ones and not see them as taking away from oneself. That’s been really important in my marriage.”

Her mother was also uniquely supportive of Jarrell’s memoir. At the end of I’m the One Who Got Away, Jarrell writes of the encouragement and love she received while writing this story of her family — something that many writers know is hardly the case with most family memoirs. Though not without its “hard conversations” she admits, there was also intense support. “Once again my mother has put my aspirations before her own, and has tried to approach reading it as she would a story about someone else.”

There was also a measure of healing that came from Jarrell’s writing. “I was really scared to tell my dad about the book,” she says. “When I finally did, I couldn’t believe the weight I’d been carrying around with me. It could have gone another way but he gave me his complete blessing and was happy for me. My husband summed it up best: he said in telling my dad about the book I came out of hiding. That really hit me given that I’d literally hidden from my dad for so many years. And that’s the real healing: being able to own what I think and feel. Coming out of hiding and saying, yes, this is how I see the world.”