Books

Andrea Dworkin Is The Controversial Feminist Writer We Need Right Now

If you Google “Andrea Dworkin” you can never be entirely sure of what you’re going to get. In just the last few weeks alone her activism and ideology has been referenced in everything from an article about Kylie Jenner and toxic makeup culture, to an anti-abortion blog post about the Ford/Kavanaugh hearings, and a lifestyle op-ed critiquing Melania Trump’s recent “Out of Africa” wardrobe inspiration. A writer, activist, and self-proclaimed “feminist militant”, Dworkin is arguably one of the most controversial figures in the modern feminist movement. She has been accused of authoring the philosophy that all sex is rape (false); vilified for dividing the second wave feminist movement into two warring factions (sort-of true); and attributed with countless other claims of various merit.

“Hardly anybody is as misunderstood as Andrea,” feminist writer Gloria Steinem said in a 2000 interview with BUST Magazine, in which she and riot grrrl Kathleen Hanna disagreed on certain facts of Dworkin’s activism. Theirs is not an uncommon exchange, especially among feminists. Reactions to Dworkin run the gamut between galvanizing and polarizing. She’s been held up as both the ultimate feminist and feminism’s antithesis. An entire page of the Andrea Dworkin Online Library website is dedicated to myth busting the lies that have been told about her. Still, it’s hard to be sure whether you’re ever getting the straight story on Dworkin or the knee-jerk response of someone who, like so many, just doesn’t get her.

Intercourse by Andrea Dworkin, $17, Amazon or Indiebound

I’m not even sure I understand what Andrea Dworkin was trying to do, entirely, even after submerging myself utterly in her writing; which I did first as a student and then again much more urgently, viscerally, in the midst of the #MeToo movement. It’s become nearly impossible to separate Andrea Dworkin from opinions about Andrea Dworkin — what has been said and written about her far exceeds what she said and wrote herself. Still, beneath the many layers of controversy we do have what Dworkin actually said, did, and wrote. And I think women need her militant feminism now more than ever.

In Dworkin’s writing (13 books in all) her anger is laid bare at a time when women’s anger, in public and in print, was far less accepted and celebrated — even by fellow feminists — than it is now. In what became her most recognized title, Intercourse, published in 1987, Dworkin examines the role of sex within a male supremacist society, (sex between cis-gender men and women, in this case.) With acuity and ferocity, she argues that intercourse between men and women within any patriarchal construct will always require the subjugation and subordination of women. It’s the book that’s (strategically deliberate) misreading inspired the misattributed “all sex is rape” claim Dworkin would become known for.

"To her detractors, she was the horror of women's lib personified," writes feminist journalist Ariel Levy, in the forward to Intercourse. That book would be credited with inciting the argument that split second wave feminism in two. It was the book Dworkin considered her “Rorschach inkblot in which people saw their fantasy caricatures” of her, her anger, and her activism. “Reviled in print” Dworkin wrote of her book; she described being encouraged to soften the book with an introduction designed to make her likeable, or to publish under a pseudonym. She did neither.

But the great value in Dworkin, aside from everything she wrote, is how she wrote it. Her work is without euphemism. There is little nuance. Her accounts of assault, abuse, and rape are matter-of-fact and explicit. She writes with unwavering authority. It is this authority, perhaps more than anything else, that drives Dworkin critics rabid — and that contemporary feminists can learn from. She tells you how it is. She knows of what she writes. She is not wrong. You could tell Dworkin she was wrong, but she would not believe you; she didn’t, in any of her writing, flinch.

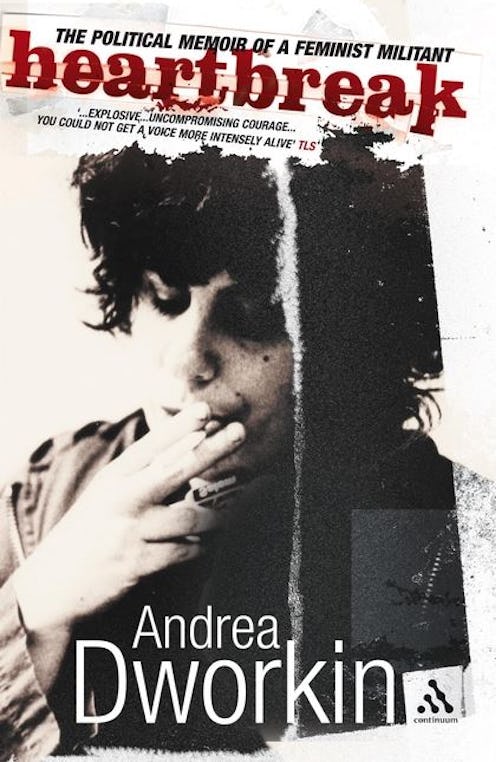

Heartbreak: The Political Memoir of a Feminist Militant by Andrea Dworkin, $13, Amazon or Indiebound

“I have been asked, politely and not so politely, why I am myself. This is an accounting any woman will be called on to give if she asserts her will,” wrote Dworkin, in the preface to her 2002 memoir, Heartbreak, which charts specific moments in her childhood, education, abuse, and activism. An accounting, yes; but an apology Heartbreak is not. Where other memoirs might tend to navel-gaze, Heartbreak asserts. Where other women writers might question who they are, (this is what we are socialized to do, after all), Dworkin tells you who she is. Where other women writers might apologize for why they are who they are, (again, socialized), Dworkin offers clear answers.

“Here’s the deal as I see it,” Dworkin wrote, considering her critics and those who would have her explain herself. “I am ambitious — God knows, not for money; in most respects but not all I am honorable; and I wear overalls: kill the bitch. But the bitch is not yet ready to die.”

In a New York Times op-ed, published days after Dworkin’s death in 2005, Catharine A. MacKinnon asks who was afraid of Andrea Dworkin? Her answer is those who did not underestimate her: accumulators of power, upholders of the status quo. “Threatened by this Jewish girl from Camden, N.J., the minions of the status quo moved to destroy her credibility and bury her work alive,” MacKinnon writes. They’re the same people who are now — though it may not seem like it, at times — afraid of women like Tarana Burke and Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi; afraid of anyone who marched on January 21, 2017; afraid of anyone who has hashtagged #metoo.

Dworkin’s writing — or, at the very least, the authority it exemplifies — was written before she would live to see its self-evidence. But I think we see it and need it, now, that militant feminism and everything it asks of us. You can disagree with her arguments all you like — and, to varying degrees, I do too — but you must bask in her assertion of them.