Books

What It's Like When You Discover You're An Undocumented Immigrant At Age 13

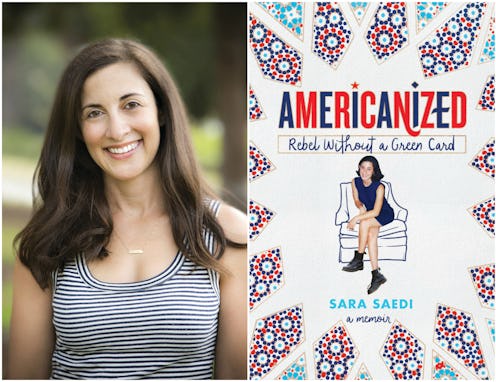

At 13, bright-eyed, straight-A student Sara Saedi uncovered a terrible family secret: she was breaking the law simply by living in the United States. Only two years old when her parents fled Iran, she didn’t learn of her undocumented status until her older sister wanted to apply for an after-school job, but couldn’t because she didn’t have a Social Security number. Fear of deportation kept her up at night, but it didn’t keep her from being a teenager. In her powerful memoir, Americanized, Saedi writes about her experiences as an Iranian-"American" teenager, and Bustle has an excerpt from the book below!

From discovering that her parents secretly divorced to facilitate her mother’s green card application to learning how to tame her unibrow, Saedi pivots gracefully from the terrifying prospect that she might be kicked out of the country at any time to the almost-as-terrifying possibility that she might be the only one of her friends without a date to the prom. It's a timely reflection on the realities of immigrant lives, a must-read for anyone who has ever struggled with their identity or finding their place in the world. Keep reading below for an excerpt from Americanized, on shelves now!

Americanized by Sara Saedi, $12, Amazon

Chapter 12: Home, Sweet Homeless

By my senior year of high school, I can say with total confidence, I’d seen my dad cry approximately one million times.

I can’t remember the first time he’d burst into tears in front of my siblings and me. Maybe it was at the end of The Little Mermaid when Ariel got legs and left her dad at the bottom of the ocean. (Seriously, WTF, Ariel? No dude is worth leaving your whole family for.) Or maybe it was one of the rare times he was able to talk about his brother even though he was still paralyzed by the grief of losing him. Or maybe it was one of the many times he looked at my mom and spontaneously declared how much he loved her. I couldn’t tell you. But I can tell you the first time I saw him cry from shame. And I was the 17-year-old asshat who brought him to tears.

“I’m sorry,” he mumbled in Farsi, his arms folded across his chest. “I’m sorry you don’t want to live with us.”

We were at Dayee Mehrdad’s house, deep in the wooded hills of Saratoga, California. We were sitting across from each other on the bench of a bay window that looked out onto the long, steep driveway that led to their magnificent English Tudor. The room was large and well lit, and came with its own entrance and bathroom. It was the home’s guest quarters, which doubled as my aunt Geneva’s sewing room. It was also where I’d decided to run away to without my mom, dad, and brother. So what if I suffered from full-fledged panic attacks every time I drove our beat-up ’88 Camry through the winding, narrow roads to my new temporary digs? My uncle’s house was big and fancy, and I had a queen-size bed all to myself.

I can tell you the first time I saw him cry from shame. And I was the 17-year-old asshat who brought him to tears.

I’m sure that as my dad bawled his eyes out, I begged him to stop crying. I’m sure I apologized for being an ungrateful brat. I’m sure I hugged him and told him that I was proud of him and that he had nothing to be sorry for. But it’s just as likely that I froze. I’ve always loved the fact that I have a dad who openly weeps. I’m glad a guy who wasn’t void of emotion raised me. But in that moment, I wished he were one of those stereotypically cold, distant American dads or those stoic, strict Asian dads my friends always complained about. Those guys never cry, right?

But let’s pause for a moment on my dad’s red and puffy face, and cut to the events leading up to our provisional estrangement. It was three months earlier, the summer of 1997 to be exact, when my mom told me that we were putting our beloved home on the market. Soon our charming black-and- white house on Pinewood Drive would no longer belong to us. It would belong to people who could afford to live there. A family of American citizens or, at the very least, a family with green cards. A house with a swimming pool was not fit for the Saedis. We were a ragtag team of undocumented immigrants, and for us the American dream was more elusive than Banksy’s true identity.

“But what about my collage?” I cried when my mom told me the news.

I had spent several painstaking weeks cutting out my favorite pictures from issues of Us magazine (back when it was still a respectable monthly publication). It had required at least two rolls of double-sided tape for the work of art to take up one massive wall of my bedroom. It was my pride and joy. My older, college-educated cousin called it postmodern. I had no idea what that meant, but I totally agreed. And there was no way I could take apart every single picture and replicate the masterpiece in another bedroom. Izzy and I had also created a mural on another wall, and had taken great care to paint my blinds with the colors of the rainbow. I was hoping any potential buyers would be deterred by the thought of a fresh paint job and replacement blinds, but that wasn’t the case.

"We were a ragtag team of undocumented immigrants, and for us the American dream was more elusive than Banksy’s true identity."

My parents made it seem like they just wanted to downsize. With my sister out of the house, and with me a year away from college, they didn’t need all the space. Why not live in a smaller, generic town house in a less expensive part of south San Jose that was twenty minutes farther from all my friends, my job, and my high school? But I knew what was really happening. Peninsula Luggage was floundering, and they could no longer afford our mortgage and my sister’s college tuition.

Here’s the thing. As an undocumented immigrant, you’re screwed when it comes to filing for student loans to send your kids to college. Though it may have been tempting to commit a felony and covertly check the box that read “American citizen” on the application, my parents knew those financial aid peeps meant serious business. From what we’d been told, they’d conduct extensive background checks into our immigration status. A false claim would have been considered criminal activity and would have been grounds to deny our adjustment-of-status application and deport us. So instead, my parents tried to scrape together every penny to pay for my sister’s college in full. Even though my dad worked as a waiter and bus driver to put himself through school, my parents hated the idea of my sister getting a job to help with her tuition. They wanted her to focus solely on her education. She would defy them and get a job anyway because, like me, she suffered from immigrant child guilt complex.

My parents had been self-employed for my entire life. They’d never had the benefits of a steady salary or paid vacation days. Their income was always unpredictable, and any time off or a lull in their business would impact how much money we had for bills and groceries each month. But luggage sales were only a small portion of Peninsula Luggage’s cash flow. The main source of income was cocaine and illegal firearms. Not really, but I always liked to pretend the business was a front for the Persian mafia. Most of our profits actually came from luggage repairs.

My parents had accounts with the various airlines and were hired to repair bags the airlines had damaged. Each day, my dad donned a white lab coat with his name, Ali, embroidered above the front pocket, and drove his giant red van to the San Jose and San Francisco airports to pick up suitcases in need of fixing. When his van wasn’t filled with luggage, my friends and I would ride around in the back and slide up and down its slick floor anytime the car slowed to a stop. His employees loved working for him, and one even asked if my dad would be willing to sponsor him to get a green card. My dad had to break the embarrassing news that he couldn’t, because he didn’t have a green card, either. Despite his cheery disposition, I knew my dad hated what he did for a living.

“It’s a thankless job,” my dad always said of the business. “You’re dealing with unhappy customers all the time.”

But you’d never know this from the smile on his face when he got home around 9:00 p.m. and took off his white lab coat. The man was relentlessly upbeat and positive. “Don’t worry, be happy” remains his mantra. Which was probably why I didn’t realize the business was in a financial slump. Unbeknownst to me, after taking out an equity loan on our house to help pay my sister’s tuition, my parents couldn’t keep up with mortgage payments. If we didn’t sell our house, the bank would put it in foreclosure.

I was 11 when we moved into our home on Pinewood Drive, and we would move out on my 17th birthday. In hindsight, I was a psycho bitch throughout the ordeal. We’d be moving into the sixth house we’d lived in since we arrived in America, while my high school friends continued to occupy their childhood homes. They each had walls in their houses that documented their height and growth spurts, beginning with the year they could stand on two feet. They had neighborhood cookouts, and could paint and decorate the walls of their bedrooms with every assurance that they’d never have to pack their bags and leave. We never had that sense of security. We bounced around from house to house, usually opting for the more affordable and less desirable parts of town. Anytime we had money trouble, my parents would say we were rich in love. And we were. But love doesn’t pay the mortgage. And it also doesn’t buy a colorful collection of Doc Martens.

"Anytime we had money trouble, my parents would say we were rich in love. And we were. But love doesn’t pay the mortgage. And it also doesn’t buy a colorful collection of Doc Martens."

Six years was the longest we’d lived in any house, and I had become hopelessly attached to our San Jose neighbohood. I loved that we lived within rollerblading distance of a local Japanese market that sold candy with edible wrappers. We still lived off the beaten path, but Pinewood Drive was much closer to my friends and school than the San Jose locales my parents were now considering. As pissed off as I was at my baba and maman for putting our house on the market, I also sympathized with their predicament. I didn’t want them to lose any more sleep over our financial problems.

But once we officially sold our house and moving day came around, I was inconsolable. On the inside of my closet door, I wrote an epic poem to the new owners telling them the house would always belong to me:

PINEWOOD

Money means nothing to me. Objects make me smile for a second. But this home I can’t let go of.

These walls, I’ve cried for.

I’ve had screaming fights in this bedroom. I’ve danced crazy all alone.

I’ve stayed up all night with loved ones.

I’ve talked on the phone with boys I’ve loved.

This has been my shelter from the storm. This is where I wrote my poetry.

This is where I’ve wanted to die.

These are my memories you’ve taken from me.

So you can paint over my pictures, erase these bitter words.

But one thing won’t change, the life that’s been spent.

This home is a part of me, And I’m a part of this house. You can sleep here if you like.

You can buy it with your money.

But my music lingers.

These walls will miss my family’s voice. So this place you call home,

Will always belong to me. One day I’ll buy it back.

I like to imagine the new family was so touched by my poignant words that they decided not to paint over them. Perhaps they could tell that whoever wrote it would be a writer someday and that eventually the poem would be worth more than the house. Honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if they leave me the place in their will.

October 6, 1997

My birthday is on Friday. The death day. The day we leave. My last few days of being sixteen, and living in this house. Why is this life so twisted and broken?

Even though I shouldn’t, part of me blames my parents.

I know they are worse off than I am. But I know they want to get out of here. I hate every happy naïve stupid person. And I hate feeling sorry for myself. And I hate being in this room. These walls are mocking me, laughing at my tears...

After we sold our house, we were officially homeless. We hadn’t found another place to live and had to regress back to our old fobby selves and shack up with relatives. My par- ents opted to move in with my aunt and uncle in their modest three-bedroom house in Cupertino. Even though their place was walking distance to my high school, I decided that I didn’t want to be in such tight quarters. Instead, I would move in with Dayee Mehrdad. Both his kids were out of the house. Of course he and my aunt would love the idea of a teenager suddenly living with them. They had enough room. They weren’t just rich in love; they were rich in money. Plus, my aunt Geneva totally dug me. She never learned to speak Farsi, and I would hang out with her at all our family parties and talk Oscar predictions. There was a good chance that after I’d lived with them for a few days, they would beg my parents to allow them to adopt me...and then I’d get a green card in no time. I lasted two days at my uncle’s house.

My parents were a mere five miles away, but it felt like they were on the other side of the world. I worried that I had created an unbridgeable divide by rejecting them and choosing my uncle, with his elegant home in the promised land of Saratoga. I cried myself to sleep from loneliness. It wasn’t my aunt and uncle’s fault. Their generosity over the years could fill up this entire book, but their lives functioned differently from those of my parents. They didn’t have kids in the house and were used to doing their own thing. They slept in separate bedrooms because my uncle’s snoring was so loud it was inhumane. They also didn’t eat dinner together, because my uncle’s dining preferences still included eating at midnight with his gin martini and then going straight to bed.

"There was a good chance that after I’d lived with them for a few days, they would beg my parents to allow them to adopt me...and then I’d get a green card in no time. I lasted two days at my uncle’s house."

The day I arrived at my uncle’s house, he gave me a hundred dollars to buy my own groceries. He explained that they didn’t really cook and usually fended for themselves for dinner. I tried to turn down the money (taarof!), but he wouldn’t let me. I didn’t tell him that I didn’t know how to cook and that I’d never bought my own groceries. Instead, I hoped they wouldn’t judge me when I dined on Noodle Roni like the peasant that I was.

Maybe it was the thought of home-cooked Persian meals that lured me to my aunt’s house in Cupertino. Or the fact that eight-year-old Kia and I were inseparable, and it felt wrong to abandon him. Or that in two days, I hadn’t figured out how to get the hot water to work in my uncle’s bathroom and that no form of deodorant would mask the stench of my body odor. No, I’m pretty sure what completely did me in was my dad, sitting on that windowsill, apologizing for selling our house and for the mess that we were now in. And then, through his tears, he apologized for failing me.

But he’d never failed me.

When my mom and dad had left behind their entire country to give me a better life, they didn’t write angsty poetry on the walls before they made their departure. They just left...knowing they might never return. Not to my grandfathers’ graves or my mother’s childhood home or the site of their first official date. If they could be that resilient, then I could move to a different part of San Jose without making such a giant fuss about it.

“I don’t want to stay with Dayee anymore. I want to live at Khaleh’s house with you guys,” I told my dad, now through my own tears.

My declaration to end our 48-hour estrangement didn’t slow down my dad’s crying, but I could tell his emotions had taken on a different form. After months, he’d finally been absolved of his guilt. I only wish I’d told him sooner that he had nothing to feel guilty about. I packed up my suitcase and explained to my uncle that I felt bad about leaving my parents. I tried to give him the grocery money back, but in typical Persian-uncle form, he refused it.

That night, I went to sleep in a cozy bed at my aunt’s house, while my parents slept on the floor of the same bedroom. One more sacrifice in a string of many. As I looked down at my mom and dad, it dawned on me that a house doesn’t make a home without the people who live inside it. As cheesy as it sounded at the time, my mom and dad were right: crammed in that tiny bedroom together, we were still rich in love.

As I looked down at my mom and dad, it dawned on me that a house doesn’t make a home without the people who live inside it.

A month later, we moved into the Camden Village town houses right off the Camden exit on Highway 85 South. I didn’t complain about the long drive to school, or the fact that we had to get bunk beds for my room so that my sister would have a place to sleep when she came home from college. I would even go on to make another collage. If I had to name the piece, I’d call it:

Resilience.

Excerpt copyright © 2018 by Sara Saedi. Published by Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.