Books

This Poetry Collection Might Help You Make Sense Of The State Of The World Right Now

“Here’s the problem — is it a problem? — with writers and poets: we think every moment is worthy of a poem,” Ada Limón tells Bustle. “When people say they can’t find anything to write about, I realize I feel the exact opposite. There is too much to write about. Everything is weird and bizarre. Look how we wear clothes even though we are animals, and look how we have jobs and carry small personal computers in our palms and drink a little barrel aged corn water to loosen up now and again. All of this is strange. All of this is worthy of a poem.”

Other things the poet finds worthy of verse? The silver maple tree. The beetle. The crushed silver soda can. And, if you read her books, so much more. “But when something absolutely stops me, holds me still, it’s usually because the moment feels surreal and illuminated, as if that image is so solid you might be able to reach out and touch it. When that happens, I know a poem is beginning within me.”

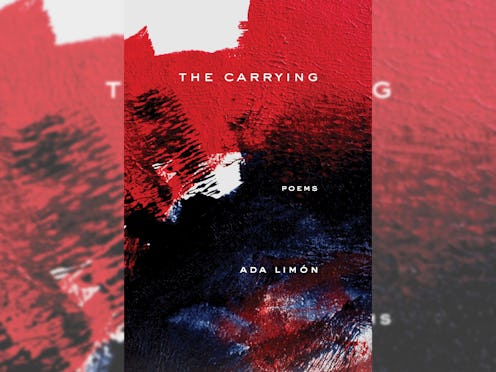

Limón was named a National Book Award finalist for her 2015 poetry collection Bright Dead Things (also a New York Times Best Poetry Book of the Year and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award) and the author of four other books of poetry. That includes her latest collection, The Carrying, out from Milkweed Editions on August 14.

“The day I got the call about the National Book Award, I almost collapsed,” Limón says, when I ask her about that moment. “I had been on the longlist, but really had no idea I’d be chosen as a finalist. It felt like my book had suddenly grown cool fiery wings. It was beyond me. Bigger than me. The book was having a life all its own.”

The Carrying by Ada Limón, $22, Amazon

But, the poet, whose first book came out over 12 years ago, says it didn’t change the way she thought about her own writing. “I threw a little party at a Brooklyn bar, my controlling boyfriend and I broke up, I lost a few pounds, but other than that, my life moved steadily forward in its own zigzag way,” Limón says. “I learned, then, that writing was more about the creation of the work and less about how it’s received. Of course, being read was and is important to me. I always wanted to create poems that people would actually read and share and care about it. But the only way I know how to do that is to create poems that really mean something to me. Maybe this sounds overly simple, but it feels true, that’s what I’m still trying to do, I’m trying to write something that matters.”

"I learned, then, that writing was more about the creation of the work and less about how it’s received."

The Carrying is a deeply intimate collection, and fans of Limón might likely consider it her most personal collection yet. It touches on everything from the current political climate and nature to love and grief; and a fair amount of the collection is about the struggle of infertility, the deep desire to have a child.

“I think that’s why I’m having some personal anxiety about this book being in the world,” Limón says, when I ask her if The Carrying is as autobiographical as it reads. “I am proud of the work and the poems, but I am also a bit dumbfounded as to why I shared so much about my own body.”

And she does share a lot of her body: Her crooked spine as a child; an MRI of her brain; her tangled hair and bra-less days; a fertility clinic sonogram of her ovarian follicles. “Of course, the answer is that I needed to do it,” the poet says. “I needed to write about it so that I could process everything that was happening. Fertility treatments are so utterly insane. I couldn’t believe so many people go through that experience all the time. I was very curious as to why we don’t talk about it more. I also became alarmingly aware of the whole mother vs non-mother dichotomy that our society seems to be obsessed with. Who is valued more and so forth. It made me want to break things. Maybe telling my story in these poems was the way I tried to break things.”

"I also became alarmingly aware of the whole mother vs non-mother dichotomy that our society seems to be obsessed with. Who is valued more and so forth. It made me want to break things."

In many of the poems collected in The Carrying, the personal, deeply human grief is mirrored by loss or sorrow, destruction or death, in nature and the animal world. In one poem, five dead animals are spotted on the road on the way to a fertility clinic. There is a raven tangled in the branches of an orange tree. Volcanic lava winds a deadly path. There is a poisoned river and belly-up fish, dead trees, and dead stars.

“It’s hard not to put one’s own grief in perspective these days,” Limón says. “How do we suffer our own legitimate sorrows while still mourning the slow loss of our planet, or how do we celebrate joy in the chaotic and panic-inducing state of our cultural and political climate, the species that are dying out, the fish, the bees. That balance feels near impossible, but also necessary. But allowing myself to feel intertwined to the natural world, to breathe with the plants and animals around me, at least gives me an opportunity to feel part of something bigger. Feeling small is sometimes the most extraordinary feeling there is. I like to feel small, not powerless, but part of something larger that carries me through my days.”

In the same way that The Carrying feels rooted in nature, the collection also feels very rooted in one particular place — the poet’s chosen home of rural Kentucky: the horses, the beetles, long grasses, prolifically reproducing dandelions. “Landscape and the natural world influence me a great deal at all times,” she says. “I feel very effected by my surroundings. When I lived in New York City, I felt like the rush and buzz of the cement city was moving through me — taxis and subways and old black gum stains on sidewalks — all of it in my body. Now that I live in a more rural town, it feels like the waving green of the grass and trees are pulsing through my blood. I suppose that rootedness you speak of is also the idea of connectedness. That pointing to the earth, that bending toward what allows us a life feels necessary. In my poems, I’m hoping to honor that connection.”

"How do we suffer our own legitimate sorrows while still mourning the slow loss of our planet..."

There are also a number of poems in The Carrying that speak to the current political moment — not just the government’s assault on the environment, but also concerns of immigration and displacement. In one poem, Limón explores the stanzas of the National Anthem that are never sung (eg. “no refuge could save the hireling and the slave”) and proposes a new one (“a song that says my bones are your bones, and your bones are my bones.”) In another, a Colombian woman is forced to smuggle a kilogram of cocaine in her cut-open breasts.

“I’d guess that all of us are having a tumultuous relationship to the country at the moment,” Limón says, when I ask her about this. “Lucky to live here, unlucky to live here. All of those feelings at the same time.”

The poet’s paternal grandfather was an immigrant from Mexico who crossed the border illegally as a child and later, as a teen, became a U.S. citizen. “He was fiercely loyal to the American dream, the idea of America, what it stood for,” she says. “Now, I wonder what he would have thought about our current situation. I wonder if people would have tried to deport him, if he would have been abused in this current contemptuous climate. This is such a large topic, but mainly can I simply say what is happening out the U.S/Mexico border is breaking my heart into a million bullets. And what is happening at the Guatemala/Mexico border is breaking my heart, too. These are violent and tumultuous times and all we keep doing is turning on each other, a snake eating its tail. I am raging most days. Grieving most days. Will it get better? I don’t know. I wish I had an answer. Somedays I don’t even have words; but mostly, words are all I have and I’m trying to use them for good, for survival, for hanging on to this spinning world.”

“I’d guess that all of us are having a tumultuous relationship to the country at the moment,” Limón says, when I ask her about this. “Lucky to live here, unlucky to live here. All of those feelings at the same time.”

It’s a spinning world that, increasingly, is turning to poetry like Limón’s to make sense of — or, at least, to assuage the grief of — it all. Since the 2016 election there have been numbered claims that poetry is “making a comeback,” that poetry readership is on the rise. The genre that was once (or that is, intermittently) “dead” has recently, again found new life. The NEA just completed a survey that indicated poetry readership is higher than it has been in the last 15 years, and that most of those readers are young people. I ask Limón if she thinks there’s a particular way poetry is speaking to Americans right now, if she thinks about that as she’s writing?

“I see poetry being read a lot more places nowadays and the shift feels real,” she says. “Even with all the anger I have to the currently political climate, what buoys me is that this is a great time to be a writer. There are so many smart, varied, and large-hearted poets writing at this very moment. I think it’s regaining popularity because poetry doesn’t have to have any answers, good poetry isn’t a polemic and it doesn’t offer a diatribe or rant. What it does is allow for nuance and space for mess and truth and complexity. It’s a place where people can come to for empathy, but also it’s a type of art form that makes space of the reader. There’s breath built right into the poems so that the reader can stand within them, breathe within them, and even be silent for a while.”

"Even with all the anger I have to the currently political climate, what buoys me is that this is a great time to be a writer. There are so many smart, varied, and large-hearted poets writing at this very moment."

Poetry, in essence, as an antidote to so many of the other ways we’ve been communicating with each other and the world, of late. “There is so much noise and madness and rage in the world right now and while poetry can live in that space, it can also live in the space of peace, of reflection, of quietude, and joy,” says Limón. “It’s the sheer rubberiness of poetry, its unconstraint, its ability to not offer only one emotion or only one fact or one answer, but a multitude of truths, that’s what gives poetry its magic power. We are leaning in to the idea of real complication. The real mess. And as much as we crave answers right now, crave solutions, crave a fix, I think we also distrust those things. What we can trust is the real complicated questions. And complicated questioning is what poetry does best.”