Books

'A River Of Stars' Is A Powerful Story About The Unique Challenges Of Immigrant Mothers

“If you’re of Chinese descent, “Ni cong nali lai?” is often the first or second question you get from another Chinese person: where are you from?” award-winning author Vanessa Hua, whose debut novel A River of Stars, tells Bustle. The novel takes readers from a factory in urban China to a rural Chinese village, all the way to the coast of California: into an off-the-books maternity home in Los Angeles, San Francisco’s Chinatown, and Silicon Valley. The answer to the question “where are you from?” is one that can — and does — determine the quality of life and opportunities of each of Hua’s characters.

“Not just where are you from,” Hua says. “Where are your people from, where is your grandfather from? The birthplace of your ancestors was thought to reveal something about your temperament and your character. The question became trickier during the turmoil and migration of 20th century China. My parents both moved much during their childhoods, ahead of Japanese invaders and during the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists. Eventually, both of their families moved to the island of Taiwan. There, they grew up in the cities; my mother’s father was a judge, and my father’s father served as a naval officer and later as a school administrator.”

"Where are your people from, where is your grandfather from? The birthplace of your ancestors was thought to reveal something about your temperament and your character."

Hua herself is the American-born daughter of Chinese immigrants, and grew up in a predominantly white community in the eastern suburbs of San Francisco. “If we needed to stock up on groceries and go out for dim sum, we’d visit the Chinatowns in Oakland and San Francisco,” Hua says. “When I was a child, my maternal grandmother lived with us, helping raise me, my brother, and sister while my parents pursued demanding careers. For her, Chinatown must have been a welcome respite, a place where she could find familiar foods and dialects.”

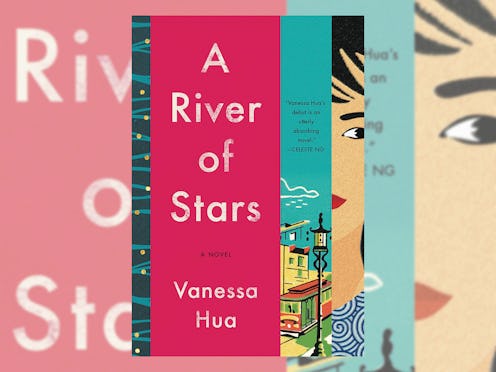

A River of Stars by Vanessa Hua, $20.76, Amazon

San Francisco’s Chinatown is, in many ways, a welcome respite for Hua’s characters as well. Scarlett is an unwed mother, pregnant by the boss of the factory she worked at in China, and an aspiring America citizen who is in ever-increasing danger of overstaying her visa to the United States. Daisy is a pregnant teen and U.S. citizen who grew up abroad, in Taiwan. At the novel’s start, both women have been sent away to a secret maternity center in the United States called Perfume Bay, where they are expected to carry out their pregnancies thousands of miles away from the eyes (and judgements) of their families and communities.

Though much of A River of Stars takes place in Chinatown, the novel also traverses the globe, taking readers to places as disparate as a remote Chinese neighborhood and a Silicon Valley hospital; San Francisco’s Mission District and a factory in urban China — following Hua’s interest in using her debut to explore, among other things, globalization.

“Goods, services, and people moving across borders fascinate me,” the writer says. “Globalization is reflected in every aspect of life, in what we eat, what we buy, who we work for and who works for us. As a former business journalist, I’ve long been interested in the micro and the macro, in the forces that move people around the world.”

“Goods, services, and people moving across borders fascinate me,” the writer says. “Globalization is reflected in every aspect of life, in what we eat, what we buy, who we work for and who works for us."

Hua visited rural China herself for the first time in 2004, on a reporting trip in the Pearl River Delta, west of Hong Kong. “I visited a toy factory, whose goods were bound for export. I wondered what it felt like to be a mother working at the factory, who lived apart from her child most of the year, and once a year visited her village. I also wondered what they thought of the toys they were assembling, if they found them strange or bizarre. A few months after I returned, I was attending a friend’s baby shower. When she unwrapped a caterpillar rattle, I gasped. I’d seen that very model of toy under production in China, and I thought about the ways we are connected — the toy created and passed by hands from one end of the ocean to another.”

A River of Stars zeroes in on the unique ways women, and mothers in particular, are affected by forces like those of immigration and globalization. Scarlett is in danger of becoming an undocumented immigrant — getting closer to the expiration of her tourist visa by the day, and fighting to gain citizenship in order to stay in the United States with her American-born child. This — Scarlett’s race against time — is a distinction that is critical to A River of Stars, and the ways Hua is adding her voice to the national dialogue about immigration.

"...I thought about the ways we are connected — the toy created and passed by hands from one end of the ocean to another.”

“The immigration debate in this country is dominated by the narrative that people are sneaking illegally over the southern border, on foot,” Hua says. “And yet, anywhere from 40 percent to two thirds of the people who are undocumented in this country came in on valid visas that they overstayed (and Scarlett is in danger of doing just that.) The immigration system is broken, but fixing with it won’t be as simple as building a wall. My novel explores these gray areas, that steep slope of precariousness.”

I ask Hua if, when she began this novel, she could have imagined that her main character’s biggest fear — that she be forcibly separated from her child by the United States government, over her immigrant status — would have such national relevance?

“We are a country of immigrants,” Hua says. “That’s our origin myth (even though our true history, of slavery, of lands stolen from Native Americans, is considerably more violent and devastating.) The story of immigration is as old as America, and yet as new as the latest arrival. The rising xenophobia under this presidential administration has made my novel and its concerns more timely and relevant than ever. Scarlett’s vigilance, her desperation and the ingenuity and luck necessary to remain with her child in this country — that all resonates with the plight of families today.”

"The story of immigration is as old as America, and yet as new as the latest arrival."

Throughout A River of Stars, Scarlett is constantly, exhaustingly, on guard. She doesn’t make a single decision without weighing its potential effects on her visa status, her risk of deportation, and the very real possibility of being separated from her child. Not only has she taken on the physical and emotional labor of new motherhood, she’s under the unending stress of trying to get her immigration papers in order as well.

“Being on guard has served Scarlett all her life, but it’s also kept her at a distance from family, friends, and lovers,” Hua says. “But her solitary existence changes after she has a child, and after she immerses herself in the Chinatown community. She finds a home, a haven. Families who have been torn apart must feel bereft, and hopefully the work of activists, elected officials, and other supporters working to reunite them may help them know that they are not alone in their struggle. As Scarlett searches for a way to fix her papers, she’s well aware of the consequences if she doesn’t. Deportation, the threat of deportation, and getting wrenched apart from her child is always on her mind, while she attempts to navigate a new country and culture and earn a living to support her family.”

The first person to break that distance Scarlett holds herself at is her fellow Perfume Bay-escapee, Daisy. Two very different characters, Scarlett and Daisy form a tenuous bond — first through their shared experience of being outsiders at the Perfume Bay maternity center, and then in the initial co-raising of their children. “When I first started writing about Daisy, I didn’t realize what a major part of the novel she would become,” Hua says. “But I’d been interested in exploring notions of citizenship, nationality, and identity, and the privilege that Daisy has by virtue of her birth in America, even though she grew up in Taiwan. It’s just the sort of freedom of movement, that potential for opportunity that Scarlett wants to preserve for her child. As I developed each character, I realized that Scarlett and Daisy could gain a greater understanding of one another — and of themselves — because of their differences. A kinship of sorts forms between them. They realize they might have more in common than at first glance.”

That kinship also forms because of their shared experiences of early motherhood. “Motherhood can feel like traveling from one country to another, in which your leave behind one life and you must grow accustomed to the rituals and culture of a new one,” says Hua, who wrote A River of Stars while pregnant with twin sons. “Amid all these changes, you can’t help but wonder who you are, who you really were, and who you will be.”

"Motherhood can feel like traveling from one country to another, in which your leave behind one life and you must grow accustomed to the rituals and culture of a new one."

She also uses her characters to challenge popular portrayals of motherhood. "In the popular imagination, sometimes it seems the only portrayals of motherhood are white and middle class and educated, suburban and middle class and straight," Hua says. "Whether in my fiction or in my journalism, if I’m writing about race or motherhood or immigration and identity and more , I’m always trying to shine a light onto untold stories, and I hope that’s reflected in my novel."

While Scarlett fights to stay in the United States legally, her child — by luck of birth — is already an American citizen. If Scarlett becomes an American citizen, it will be after a hard-won battle in the early-middle of her life — whereas citizenship will be all her child has ever known. I ask Hua if Scarlett’s America will be a different one from that in which her child grows up. “Now that I have children of my own, and am raising them in the town where I grew up, I’m able to see what has remained the same and what has changed,” Hua shares. “The country is much more diverse, compared to when I was growing up, but we still have far to go in terms of addressing socioeconomic and racial injustices and the environmental crisis. My children’s America will be determined in part by how we raise them, and there’s hope in that, in a future where we strive for equality and rights for all.”