In the months since Donald Trump has become president, more and more people have become inspired to join the Resistance — whether that means volunteering, campaigning, donating, making calls, educating themselves and others on the issues, or otherwise. Bustle's 31 Days of Reading Resistance takes a look at the role of literature and writing in the Resistance, both as a source of inspiration and as a tool for action.

You can’t criminalize a feeling, so governments have created all kinds of specific ways to outlaw queerness over the centuries. As you can imagine, queer people have always found ways around them — in exceptionally creative ways. In 1991, AIDS advocacy group ACT UP covered the house of Senator Jesse Helms in a 15-foot condom that read “A condom to protect against unsafe politics. Helms is deadlier than a virus.” Back in 1950s San Francisco, drag queens wore buttons that said “I am a boy” to avoid committing the "intent to deceive" that that an anti-crossdressing law forbade.

The world of queer literature is no exception to this creativity.

The written word is an unparalleled opportunity to reach other folks in any community. But for queer authors and creators, special care had to be taken for anti-pornography and obscenity laws weren’t violated. Creators also had to be careful to ensure they didn't reveal themselves as someone who had committed a crime like sodomy.

There was also risk for those who read early queer literature. The team behind The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian magazine in the United States, took special care to ensure the names of their subscribers were secure. In fact, one of the team members carried the subscription list with them at all times so it would never be exposed in case of an office break-in. Imagine giving over your name and address to be put on a list that – if discovered — had the potential to land you in jail. The Ladder’s first issue in 1956 had an article headlined “Your Name Is Safe!” that detailed the legal precedent the group would use to argue their list’s privacy, if necessary.

The first time the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on any homosexual issue was actually over a similar publication: ONE, a gay magazine in print out of Los Angeles from 1953 to 1967. The magazine was banned by the U.S. Postal Service for being obscene. ONE Magazine didn’t have sexual content like ads for escorts or nude images; it just had articles that discussed issues of homosexuality. “Homosexual Marriage?”, the cover story of the first issue that sold for 25 cents each, was decades ahead of its time.

A California court stated that “the suggestion advanced that homosexuals should be recognized as a segment of our people and be accorded special privilege as a class is rejected.” Four years of litigation later, the Supreme Court overturned that decision, ruling for free speech in ONE vs. Olesen (Otto Olesen was L.A.’s postmaster). This 1958 decision paved the way not only for LGBTQ+ press, but the very idea that gay people could have equal rights. That was less than 60 years ago.

The beginnings of the modern Western movement for queer acceptance as we know it today started in the second half of the 19th century in Germany. The word “homosexuality” first appears then in 1869, and in 1886, Richard von Krafft-Ebing released Psychopathia Sexualis, an academic look at sexual practices including homosexual and bisexual ones. The trend continued, and in 1897, the first queer rights organization, the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, was founded.

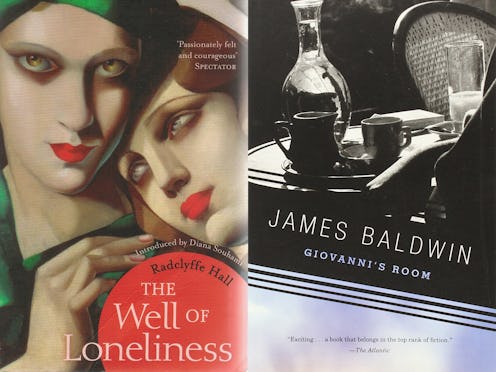

And then — finally — we reach a watershed moment for queer literature: in 1928, officials in the U.K. seized a newly-published “sex novel” and put it on trial for obscenity. The novel — Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness — tells the story of Stephen, a person assigned female at birth who loves women. A queer character who believes in their right to exist as queer! A queer character who doesn’t die by murder or suicide! A queer character who reads Psychopathia Sexualis!

The Well Of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall

The British government’s lawyer argued that “the book seeks to glorify vice or to produce a plea of toleration of people who practice it," and that it was “more subtle, demoralizing, corrosive and corruptive than anything ever written.” The lawyer defending the book claimed it was “a sombre warning which could under no circumstances corrupt or deprave.” A judge decided the book was “an offense against public decency” and ordered all copies destroyed.

However, when the book’s publisher went on trial in the U.S. in 1929, the result was different: The Well of Loneliness was allowed to remain in print in the United States.

The queer authors that followed faced many challenges besides obscenity laws. It wasn’t easy for James Baldwin to get Giovanni’s Room published in 1956, but he did it. As the queer rights movement grew in the U.S., so followed the literature: Maurice by E.M. Forster in 1971, Rubyfruit Jungle by Rita Mae Brown in 1973, Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin in 1978. The impact these and other works had on the queer community cannot be overstated. Seeing yourself reflected in the pages of a book means so much; it is a lifeline. Pre-Internet, when discovering resources and community and support was that much harder, these books helped countless people discover their own identities and know that they weren’t alone.

Today, books with queer content are still regularly challenged across the country (celebrate by reading them during Banned Book Week next month!), but we’ve clearly come a long way. The most important action we can take today to support queer stories is to keep reading. Whether you read to feel at home no matter where you are or read to spend a few miles in someone else’s shoes, keeping learning and sharing so that we move this history forward and never let it slip back.

Sarah Prager is the author of Queer, There, and Everywhere: 23 People Who Changed the World, a new critically acclaimed book that tells the true stories of past resistance leaders like Jose Sarria of the “I Am A Boy” buttons and the creators of The Ladder Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon.

Follow along all month long for more Reading Resistance book recommendations.