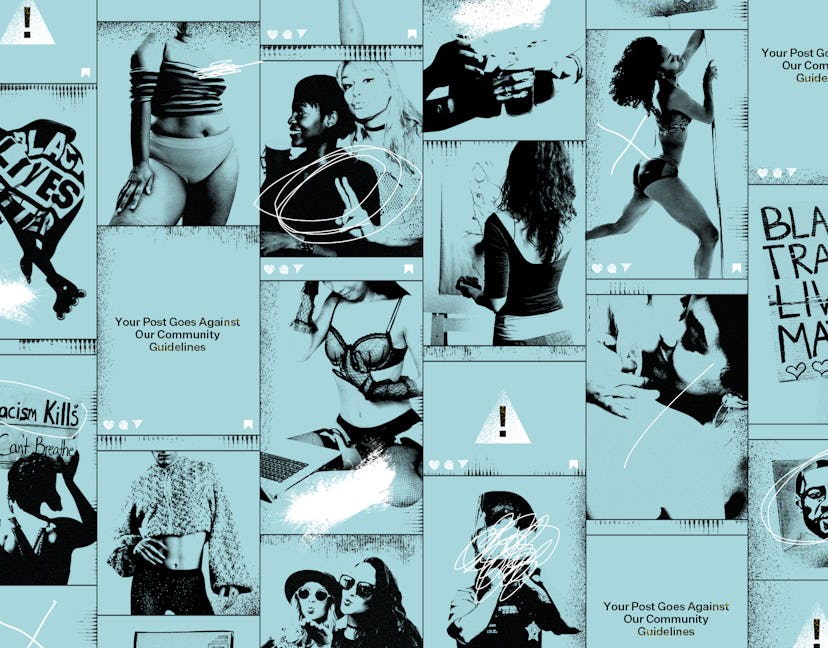

How Shadow Banning Affects People From Different Communities

What would you do if your work, your body, or your life choices were deemed to “go against community guidelines”?

This piece is the second in a two-part exploration into shadow banning and its effects. For more in-depth information about what exactly shadow banning is and how it works, please click here.

Social media platforms allow us to form communities, build businesses, and even offer a space to teach and educate others. However, as we’ve seen, the algorithms operating on these sites have the potential to perpetuate and reproduce harmful biases that their creators may possess, which some say plays a significant role in a phenomenon known as shadow banning.

Shadow banning occurs when a social media user has their content removed or obscured or their profile suspended because what they're posting is deemed to go against the platform’s community guidelines. We’ve already explored shadow banning as a concept (with a specific focus on Instagram), but what are the stories behind facts and figures? What is the real-life fall out for the people who find themselves at the mercy of the Instagram algorithm?

Many of us witnessed the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign which arose this summer when Nyome Nicholas-Williams, a Black plus-size model and influencer, spoke out about the repeated removal of semi-nude photos of her from Instagram. The incident sparked wide-spread outcry, a campaign under the hashtag #IWantToSeeNyome, and a petition that was signed by more than 21k people.

Speaking to the Guardian in August, Nicholas-Williams pointed out: “Millions of pictures of very naked, skinny white women can be found on Instagram every day. But a fat Black woman celebrating her body is banned? It was shocking to me. I feel like I’m being silenced.”

Nicholas-Williams is not the person to raise the alarm about Instagram’s alleged fatphobic algorithms. In October last year, writer Jessica Richman reported that a member of Instagram team had confirmed its algorithm detects and flags photos featuring over 60% skin. She pointed out that clothing, particularly bathing suits, worn by thin people will look different on fat people.

“Let’s say a smaller-bodied woman decides to wear a bathing suit that covers up 40% of her skin,” wrote Richman. “Now let’s imagine a fat woman decides to wear the same bathing suit. That bathing suit may have slightly more fabric due to the larger size, but that individual’s body could have significantly more skin, causing Instagram’s algorithm to flag the image even though there is nothing inappropriate about it.”

Although a Facebook Company spokesperson disputed Richman’s findings at the time, stating “We do not use an algorithm identifying a percentage of skin,” Instagram responded to Nicholas-Williams campaign saying that its semi-nudity policies needed to be reviewed. As well as apologising and reinstating Nicholas-Williams' images, Instagram also shared a statement saying it was “committed to addressing any inequity on [its] platforms.”

Since the campaign, Instagram has made changes to its semi-nudity policy, outlining the difference between "breast holding"/"cupping" and "breast grabbing," with the latter still being flagged as pornographic while the former is seen as a celebration of the body. "It may take some time to ensure we’re correctly enforcing these new updates, but we’re committed to getting this right and will continue to work with experts and community members on how we can do better," Instagram said in a statement sent to me. I was also pointed towards the broader equity work that the organisation.

Nicholas-Williams’ story is undoubtedly a victory in the fight against shadow banning, but it's also a reminder of how far we have to go. As she herself has said, “it shouldn’t have taken all of this to get a response,” and the truth is that users from marginalised backgrounds are still experiencing shadow banning on a regular basis. Algorithms contribute to our livelihoods, our personal relationships, and more, so what happens when we’re no longer seen?

The Artist

New York-based artist James Falciano remembers clearly the first time they found themself being shadow banned back in December 2018.

“I had posted a drawing of a queer couple embracing, and they were nude,” they tell me. Despite Instagram’s community guidelines stipulating that nudity in artwork is allowed, Falciano says that “all of a sudden,” they couldn’t post any new content for 24 hours. “Anything I shared would instantly [be] deleted,” they explain.

Falciano guesses that their drawings were reported by the “multitude of haters” who were filling their comment section with homophobic comments and that Instagram may have taken this as a cue to hide and remove their content.

Although their restriction around posting photos lifted after 24 hours, Falciano found that, for two weeks, their work stopped showing up under the hashtags they were using, cutting off their content from new viewers. When the visibility of content is reduced on Instagram, it will still show up on followers' feeds, but it can be restricted from being surfaced to the wider Instagram community.

For Falciano, this is a major problem. They are a full-time freelance illustrator, meaning they need to be able to be discovered on Instagram to secure commissions and earn a living through their art.

The Queer Model

Model and activist Radam Ridwan’s experiences with shadow banning have been similar. For them, Instagram has been one of their main channels to reach followers and build their personal brand, but shadow banning has made it more and more difficult.

Ridwan says that after they began openly expressing themself as queer and non-binary around February 2019, they were "increasingly shadow banned." They tell me: "I noticed that engagement on my photos had decreased significantly despite organically gaining a larger following."

They found their handle couldn’t be found when typed into the search bar: “The shadow ban for me meant that hashtags on my posts would not work and effectively exclude my pictures from appearing on the Explore page.”

Like Nicholas-Williams, semi-nudity was also a problem for Ridwan. “Posts where I appeared partially clothed started to be deleted frequently as they were automatically picked up by Instagram and reported more often.”

When asked what they think can be done to help support those who are shadow banned on the platform, Ridwan says: “Individually, we can work harder to promote minoritised populations on the app. There are still ways for us to discover these people and support their work, but we must actively search for them to ensure not only the privileged are seen.

The Queer Collective

Queer Collective Pxssy Palace has also repeatedly come up against issues with shadow banning, with posts being hidden and deleted, as member Bernice Mulenga told Chante Joseph at the Guardian last year.

Speaking about the impact of this, A.I.D., another member of the collective, explains to me: “Pxssy Palace and other collectives that centre the lives and experiences of queer and trans people of colour are a life resource. Our online presence introduces and platforms creatives, organisers and businesses that feed our community so when our content is restricted, it means that people are not seeing and getting the chance to interact with things that may help them navigate life.”

A.I.D adds: “Our collective primarily makes money from the [now virtual] club nights … So when people do not know about our events, ticket sales plummet and we barely break even, and people are depending on those funds.”

The Black Woman Social Commentator

Kelechi Okafor is another user who understands the potential financial implications of being shadow banned on Instagram.

In November 2019, Okafor experienced shadow banning after she voiced her support for mummy blogger Candice Braithwaite, who had been subjected to trolling from an account named AliceInWaderlust. The account – which was later discovered to be run by another mummy blogger, Clemmie Hooper – referred to Braithwaite as "aggressive" and said she was using her "race as a weapon."

Okafor took to her Twitter and Instagram to highlight the fact that Hooper is a midwife, working in a field where we know that Black women are five times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Okafor therefore questioned whether Hooper was fit for the role considering the targeted abuse she had directed towards a Black blogger.

After voicing her concern, Okafor’s Instagram page was suspended. Some supporters of Okafor have suggested that this was a coordinated effort from fans of Hooper. When asked who she thinks was responsible, Kelechi says: “Well, that’s something we can speculate on but we know that my page was reported enough for Instagram’s algorithm to deem it necessary to pull my entire page down and I think that’s violent in itself.”

She continues: “My page is still a source of income for me and because I questioned her legitimacy as a medical professional, that meant that my page could get taken down and my livelihood could be impacted for calling out something that is a danger to me.”

Luckily, Okafor’s followers helped her get her page back up and running, but the incident left her feeling unsettled. “I can get my page reinstated because of the people who are aware of me and able to help me with that,” she says, “but what about the people who are even more marginalised than I am?”

The Sex Worker

The sex worker community is one of the most marginalised in our society – including when it comes to online spaces. In her essay “Social Media Will Be the Death of Me: A Black Sex Worker’s Lament”, written for Wear Your Voice magazine, Adria Rose highlights how vulnerable sex workers are in digital spaces alongside (along with women, Black and brown people, and trans people): “These sites have always pitted marginal groups against the ideologically opposed masses ... Sex workers, people of colour, women, and LGBTQ+ people attract the worst kinds of trolls and all the misapplied first amendment related screeching that follows them.”

Rose also speaks about the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act and the Senate (FOSTA) bill and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) bill. Although it’s easy to assume that a bill package intended to help victims of sex traffick is a clear-cut moral win, the reality is far more complicated. Rose explains that SESTA/FOSTA has actually been “a state-sponsored, bulletproof excuse for their whorephobic and misogynist policies” and has ramped up hatred towards sex workers online.

Although Instagram did not change any policies in the wake of SESTA/FOSTA, many sex workers have come forward with experiences of shadow banning on the platform since its passing. The fact of the matter is that SESTA/FOSTA bills mean that social media companies are now liable for what their users say and do on their platforms, putting even more emphasis on the need to monitor content.

Samantha Sun, a professional aerialist, performer and member of the East London Stripper Collective, tells me "I used to get a lot more engagement, [but] whenever I hashtag anything with #stripper, #yesastripper, #sexworkiswork etc, I always notice a drop in engagement."

The Pole Dancer

The pole dancing community continues to face barriers to posting content on social media. This issue came to light recently when, in the summer of 2019, a number of pole dancers realised that some of the hashtags they frequently used were being blocked.

Pole dancer and instructor Lori Glaza tells me that there she observed mass-blocking of "pole-related hashtags including #poleinstructor, #poleathlete, #exoticpoledancer, most tricks that were labelled #pd, and even our protest hashtag #shadowpolers." She also tells me that #femalefitness was affected because it was being used by pole dancers, but #malefitness was not.

In August 2019, the pole dancing hashtags were restored and Instagram apologised after a campaign was started among the pole community and its allies. However, the incident proved how easily their work could vanish and their community could be left silenced and disconnected from one another.

For PhD researcher and pole dance performer and instructor Carolina Are, who goes by Blogger On Pole, the opportunities Instagram has offered have been crucial. “Through it, I was able to market my self-published novel, to grow my audience for my blog and to make a name for myself as a pole dancer and become an instructor,” she says. “Essentially it’s the biggest platform I use to make my voice heard.”

Are began using the platform to document how pole dancing had helped her come to terms with abuse she had survived. She also used it to connect with a supportive community of pole dancers and sex body-positive people. To lose this network would be devastating for Glaza and others like her.

Are points out that, worst of all, this kind of online suppression can threaten the community’s well being. When people’s profiles are suspended, she says, it deprives them of “the possibility to vet their clients for safety.”

Speaking about what can be done, she says: “People need to get behind this, and not just minorities, it’s not just about pole dancers: it’s about how a handful of companies with a huge monopoly over content, over information, over our data, over what’s published are getting to decide what’s appropriate to be shared.”

When I reached out to Instagram about the experiences mentioned above, a spokesperson told me that their team is "committed to addressing inequity on our platform" and have "created a dedicated team to better understand and address bias in our products." They added: "This work will take time, but our goal is to help ensure Instagram is a place where people feel supported and able to express themselves."

Despite this, users are still concerned about their future presence on the site. As Are put it: “What’s scary is that algorithms are replicating real-life inequalities – if we thought the internet was going to be an equalising force, that dream is over now.”