Case Study

The Suburbs Can Be Radical. One L.A. Neighborhood’s Restaurants Prove It.

Boyle Heights has been defying assumptions since 1876.

Los Angeles’ second suburb, first subdivided in 1876, defies commonly held assumptions about what it means to be a suburb. Boyle Heights was shaped by the waves of immigrants — including Armenian, Russian, Italian, Mexican, Black, Jewish, and Japanese Americans — who swept through the district when discriminatory lending practices, restrictive covenants, and racist homeowners associations kept them out of whiter parts of L.A.

Today, the highlands neighborhood east of the L.A. river is 95% Latinx, and home to one of the region’s most organized fights against gentrification. Remnants of Boyle Heights’ multicultural history — and the grassroots movements borne out of it — still stand today, not least of which are its restaurants and food stands.

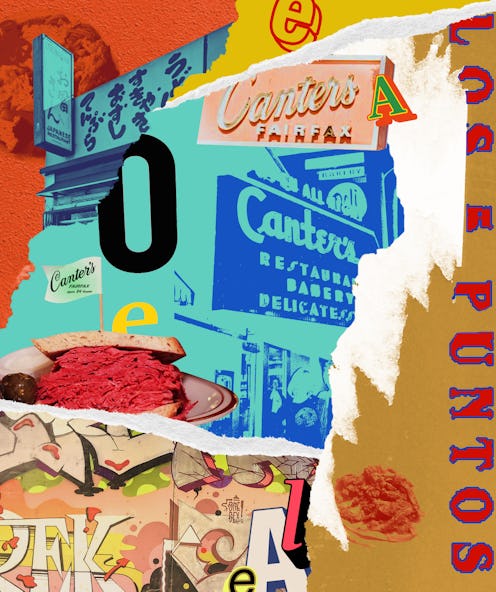

Canter’s Delicatessen

Any connoisseur of pastrami is familiar with Canter’s on Fairfax Avenue, but few know that L.A.’s most famous deli first opened on Brooklyn Avenue (a continuation of Sunset Boulevard, since renamed Cesar Chavez Avenue) in 1931. Indicative of the Jewish migration to the area from the Midwest and New York, Boyle Heights was once known as “the Lower Eastside of Los Angeles,” and was home to the largest Jewish community west of Chicago.

Paving the way for the arrival of Canter’s was a group of radical, unionized Jewish bakers, many of them refugees of Czarist pogroms, committed to preserving Yiddish culture, advocating for workers’ rights, and anti-racist organizing. A large part of the Jewish community threw their support behind the successful 1949 election of Boyle Heights native Edward Roybal, who became the first Latino to serve on the L.A. city council in the 20th century and, later, California’s first Latino member of Congress since 1879.

Otomisan

As the last Japanese restaurant in the area and the oldest remaining Japanese restaurant in all of Los Angeles, Otomisan is a neighborhood landmark and a citywide one. Opened in 1956 as Otomi Café by Mr. and Mrs. Seto, the pale yellow storefront still stands at its original location on East First Street. Now under its third ownership, the quaint shop is run by Yayoi Watanabe and her daughter, Judy Hayashi, with only three booths and a few stools at the bar. Regulars come for the katsu fried cutlet, which packs a perfect crunch, supplemented with a sushi roll or sashimi.

Japanese migration to California dates back to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited Chinese immigration and increased demand for cheap labor. Eventually, Little Tokyo extended eastward along First Street into the area, making Boyle Heights the site of the city’s second largest Japanese community before World War II. When President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942, forcing Japanese Americans to be interned in camps, a third of all students at the neighborhood’s Roosevelt High School were missing from its halls and classrooms.

As the camps closed in 1945, many Japanese Americans moved back to Boyle Heights as there was very little housing in Little Tokyo, again creating a large ethnic community in the area through the 1950s, when Otomisan would provide bento lunches for prefectorial meetings held in local parks.

Los Cinco Puntos

Opened in 1967 by Vincent and Connie Sotelo, Los Cinco Puntos is named after the five-point intersection that it overlooks. In the rear of the kitchen, women can be seen pounding, grinding and shaping masa by hand before grilling their famous corn tortillas on the plancha. In the front, a plethora of meats are arranged in trays, ready to be chopped up and piled onto tacos and into burritos beneath nopales, salsa, and guacamole. Stephen and Michael Sotelo, the family’s second and third generation, now run the joint, where succulent carnitas are a favorite, as are their charred carne asada, tender suadero, and, during the holidays especially, tamales.

By the time the carniceria and tortilleria opened, Boyle Heights was majority Latinx, and the civil rights movement was well underway. Students staged walkouts in 1968 throughout Eastside high schools, and, starting in 1969, marches for the anti-Vietnam War Chicano Moratorium protested the disproportionate mortality rate shared among Mexican American servicemen. A march in 1970 ended in tragedy when three demonstrators, one of them L.A. Times columnist Ruben Salazar, were killed as the LAPD dispersed the crowd. Every year for the past 73 years, a 24-hour vigil leading up to a Memorial Day service has been held at the Cinco Puntos intersection in Morin Square, named for decorated veteran and author Raúl Morín.

This article was originally published on