A Front-Row Seat At The Red-Sauce Ballet

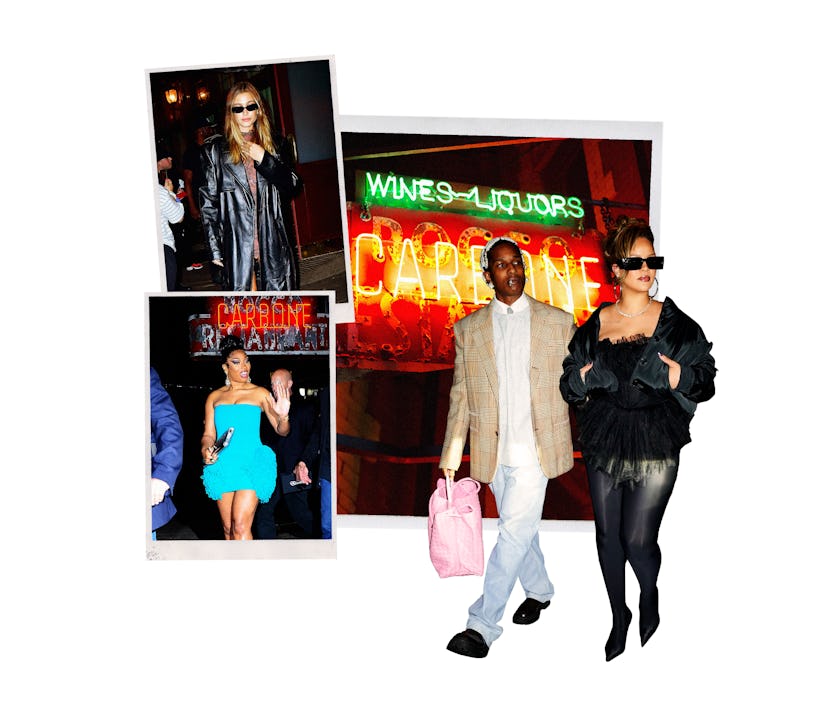

With celeb magnet Carbone and its glittering sister hot spots, the Major Food Group empire has transformed restaurant culture as we know it. Could this possibly be a good thing?

Everyone keeps calling them The Boys. These rascals. You can’t keep them down. The Boys are blamed and credited for the Vegasification of New York, the Disneyfication of dining out, the normalization of $89 veal parm. The Boys are sellouts, money men, clout chasers. They are also, the same people will tell you, brilliant. Masters of theater, dizzyingly charming, a well-oiled machine. You have to hand it to The Boys. They deliver.

The Boys are chefs Mario Carbone and Rich Torrisi, along with business guy Jeff Zalaznick, and the trio’s government name is Major Food Group. A graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, Mario studied under who we might call The Men — Daniel Boulud, Mario Batali, Wylie Dufresne — in Anthony Bourdain’s Manhattan, where big dicks ruled the kitchen and balsamic was artfully splattered across too-large plates. In 2009, Mario Carbone and Rich Torrisi opened their first restaurant, Torrisi Italian Specialties, in Little Italy. On a block known for its tourist traps, it was a surprisingly good neighborhood spot, with a seven-course tasting menu for only $50, which is about as punk as a tasting menu can be. Then came Carbone.

A glittery tribute to the red sauce joint, Carbone opened in 2013 to rave reviews, and quickly, a Michelin Star (which it later lost). Still today, it is ranked the No. 6 most desirable table in New York on AppointmentTrader.com, a ghoulish black marketplace for reservations where a four-top next week is going for $350. If Wolfgang Puck and Gordon Ramsay created the template for global culinary dominance (placeless cuisine anchored by an absentee owner-personality), then The Boys have perfected a hyperreal New York sensibility — slutty-savory dishes, photogenic preparations, nostalgia for a version of the city few of their customers have experienced — and planted it all over.

Their kingdom now spans 46 restaurants worldwide, including Contessa Boston (also Italian), Sadelle’s inside Kith locations in Toronto, Seoul, and Paris (all-day brunch inside a streetwear store), and Chateau ZZ’s in Miami (Mexican, inside a Period Revival manor). There are also the Carbone copies, in Las Vegas, Dallas, Doha, Hong Kong, and Riyadh. Just this month, they will launch a glossy coffee table book, with entire pages devoted to pull quotes like “The meatballs aren’t listed on the menu. Of course, they could be. But they aren’t. We’re prompting a conversation, and it creates this exchange. There’s texture there.”

“I always feel depressed when people aren’t trying to charm the server,” Kate Berlant says. “It’s sacrilege.”

And mamma mia, is all that texture lucrative. According to Bloomberg, The Boys earn $500 million a year serving rigatoni to celebrities in Instagrammable spaces that in turn attract tech bros, finance bros (and their halfway point, the fintech bro), plus the requisite sheiks, marketing girlies, and Amex Platinum-toting tourists. Major Food Group has become the fracking industry for Italian-American cuisine, zeroing in on any market that’s hungry for a slice of New York City cool, then pumping it full of marinara until it spews cash.

When I get an email from my editor asking if I want to spend a week in the Major Food Group Universe — Torrisi, Carbone, The Grill, and ZZ’s Club — I am surprised. That I could be paid to write about eating at opulent restaurants recalled the town car days of print media, Tina Brown putting lunch on the Condé tab. When men wrote essays! (As a job, not a hobby.)

The Boys’ restaurants aren’t exactly the coolest spots in town, nor the most refined. But their rise tracks everything that’s so fevered about dining in 2024. Thanks to social media, every asshole is a foodie now. In New York City, everyone, it seems, is at every restaurant, every night of the week. TikTok in particular has shifted the knowledge base for status seekers, adding hot restaurants to a list of cultural touch points for the clued-in alongside It Bags and rare sneaker collabs. Resy has paradoxically democratized exclusivity, turning every evening into a humiliating standoff between diner, host, reservation bots, and automated texts. And Major Food Group is at the center of the swirl: shiny, celebrity-laden — Tables to Get, legibly so — for the broadest possible audience of People Who Want Tables and Can Afford Them.

“You could argue what’s happening right now is because of Major Food Group,” New Yorker food critic Hannah Goldfield tells me. “They’ve created an archetype — so sexy, so theatrical, so hard to get into, so expensive.” The exclusivity compounds the appeal: “Carbone is like Rao’s now,” she continues. “It’s really f*cking hard to get a table, if not impossible. Unless you know someone.”

I. Torrisi: Soul Search

I know someone. MFG’s Miami-based PR maven, Lauren, has secured me a table at Torrisi at the somewhat unglamorous time slot of Monday at 9:45 p.m. I arrive in an Eckhaus Latta T-shirt and vintage Versace pants, hoping to blend in as a youthful influencer, but also to assert my role as critic. An outlier among the crypto bros, an epicure the kitchen will strive to impress.

Torrisi has the clean aesthetic of a boutique hotel: exposed brick, brass fixtures, warm neutrals and moody greens, specials spelled out on a 1940s sandwich board — details that suggest frictionless luxury for optimizers. Cocktails are sweet, servers are aggressively cheerful. “Isn’t it incredible?” one grins after we devour the salty Italian and American hams with zeppole. “Isn’t it the most delicious dish?” he sings after the clam boule (it’s quite good). Yet I get the feeling we’re being rushed. Maybe my outfit isn’t translating, my non-influencer skin and dry hair outing me as bereft of disposable income.

I’m on a heterosexual safari. Within 15 minutes, one of the marketing girlies next to us is showing me dick pics from Tinder suitors on her phone.

Or maybe it’s the crowd. Nate Freeman, who wrote a profile of The Boys for Vanity Fair, told me the room at Torrisi is “spectacular… whenever I go, it’s movie stars and art collectors and billionaires.” Tonight I see none of the telltale horn-rimmed glasses of the art collector, nor the billionaire’s Rolex. I do see Apple Watches. Men in crossbody bags, girls in white sneakers, everyone bored by their money. “We’re not talking about your recent college grad foodie who’s saving up their coin to go to a meal they’re dreaming of,” Amiel Stanek, an editor at Bon Appétit, tells me. “These are people who are trading experiences like they’re commodities.” Alison Roman, cookbook author and leader of the shallot revolution, has only been to Torrisi once. Its vibes, she found, were off. “The pasta was fine,” she tells me. “But it has no soul, and the clientele is enough to keep me away until I die.”

The soul of an empire is tricky to locate, especially when the mozzarella is stretched from Doha to Dallas. The Boys insist it’s still there. “We’re storytellers,” Carbone tells me over Zoom (camera off). “Regardless of where in the world you are, [if] you’re consuming a Major Food Group product, you’re going to leave with a better understanding of what that place was than when you came.” This seems like a low bar for narrative comprehension, and from where I sit, there is one story being told: clout.

There is no shortage of Torrisi content on TikTok, especially from former reality stars: Real Housewife Bethenny Frankel saying she wants to “live in a bed of Torrisi tortellini”; Bachelor alum Matt James in a teal windbreaker and beanie filming his entire meal (“The Jamaican beef ragu had kick like Kung Fu Panda!”). Commodities traders, if you will.

“We see ring lights all the time,” Torrisi laments, speaking to me from his wood-paneled office. “Some of these people aren’t even influencers, or people that even get paid to do this. It’s shocking how noxious that is.” I ask if he’d rather return to a time before phones and can see him mentally calculating the revenue that endless TikTok buzz has won them. “I don’t really see a lot of upside in the restaurant during the experience. [But] there’s definitely upside for restaurants in general… like the amount of eyeballs that you’re gonna get if you do something well, whereas, in the past, you’d have to get access to press, you know?”

Kate Berlant, the actor and comedian who frequently rhapsodized about restaurants on her podcast, POOG, is more dogmatic about clout-seekers: “You take yourself out of the theater when you do that, and then you’re no longer a diner.” Dining is a ballet. The choreography is sacred, and everyone on the floor is both dancer and audience. “I always feel depressed when people aren’t trying to charm the server,” she tells me. “It’s sacrilege.” And how about the rush of being seated at the impossible-to-get table? Aren’t we all guilty of wanting status? “I feel pure of heart,” she says. “I mean, yes, there’s a part of me where I wish it were the ’90s or whatever,” referring to the go-go era of American Psycho power lunches. Still, she insists, “I’m in it for the right reasons. I’m a fan.”

II. The Grill: The Price of Nostalgia

If you wanted to clink glasses with power-suited diners in the ’80s, you would have gone to the Four Seasons, which became The Grill after The Boys took it over in 2016. In an act of commendable restraint, The Boys didn’t pave it over for some bland hotel steakhouse, they simply restored Philip Johnson’s 1959 interior to its sumptuous former glory, with its 20-foot-high ceilings and chainmail curtains lining the windows.

Two days after my Torrisi visit, I ascend the staircase onto the main floor of The Grill with my friend Matthew, who happens to be New York magazine’s food critic. A genteel hostess leads us to the bar, where a second genteel hostess materializes with two glasses of champagne. “Our compliments.” Matthew grins coyly as she pours the bubbles. “And may I ask,” he says, “what’s the cépage?” I do not know what cépage means. I detect the faintest glimmer of panic before she narrows her gaze and gingerly pulls the bottle up. “I believe it’s an even 33% between all three grapes,” she smiles.

I begin to focus on my stomach — ballooning, churning, expanding — and think of the syringe they use on cows to release methane from their cavernous insides.

In her memoir, Tina Brown describes eating lunch at the Four Seasons early on in her career, when her boss finds her at a distant table and warns her she’s in “Siberia.” Matthew and I, on the other hand, get the best seat in the house. Corner booth. View of the entire room. I can feel Si Newhouse’s assprint beneath my cheeks, the assorted perfumes of Rupert Murdoch’s various wives wafting past.

We order gluttonously. I ask our jocular server if it will suffice. “I’ll fill in the gaps,” he responds. Have you ever heard anything more beautiful? The prime rib arrives with a fat dick of horseradish via tableside trolley. A second trolley arrives for the “pasta a la presse.” (Mario procured the enormous 100-year-old press, we’re told, on a trip to New Orleans.) The machine operator presents a glistening terrine of roasted poultry — pheasant, squab, duck — that then goes into the press, and turns the wheel with apparent effort. It emits a concentrated jus, poured nonchalantly onto tagliatelle. The meat is discarded. We leave nearly four hours after arriving and I understand why men work in finance.

“I love theatrics,” Alison Roman says of The Grill. “I love commitment to the bit, and I love when people have a budget and they do something with it. It’s such an historic New York establishment, and I do think they did it justice.” The Boys have done justice to a nebulous past, an imaginary one for people like me who were never 1980s businessmen. But good theater fills in the gaps.

III. Carbone: Almost Famous

When I spoke with Mario, I reminded him that emblazoned on MFG’s homepage is a quote from the Vanity Fair piece: “Mario Carbone built the most celebrity-studded restaurant on earth.” Is it safe to say he’s proud of the celeb clout? He demurs. “I’m proud that celebrities or anyone of prominence, athletes, whatever, choose our restaurants.” As I write this, the pop star Sabrina Carpenter and her now-ex actor boyfriend Barry Keoghan are spotted at Torrisi, Jay-Z and Beyoncé at ZZ’s, and at Carbone, pop star Halsey and her actor fiancé Avan Jogia, star of 2021’s Resident Evil: Welcome to Racoon City. Everyone I know says Carbone is washed. In October, the New York Times wrote the franchise was overextended. Would I survive what it had become?

I arrive at Carbone on Thursday at 7 p.m. (enviable). My date (a Reuters journalist with zero power in the food industry) and I are once again treated like masters of the universe, whisked past the poors in the front room, through the velvet curtain and into a booth in the interior salon. Dean Martin is blasting. The room is rigidly gendered. I’m on a heterosexual safari. Packs of men occupy one table, Equinox pecs bursting from their button-downs, while the next booth is all bandage dresses and thin, stacked gold jewelry. It makes sense: if you’re going to spend $500 on a reservation, you don’t want to impress a date, or worse, your wife. You want to impress your boys.

The room is electric. Our server looks like the son of Antonio Banderas and Paul Mescal with a hint of the Dos Equis guy, and grins throughout our tableside Caesar-salad tap dance. I ask for a light and tannic red, a little sweaty, Northern Italian maybe? “I’ll bring you something beautiful,” says the Most Interesting Man in the World. We make friends with the marketing girlies next to us and within 15 minutes, one is showing me dick pics from Tinder suitors on her phone. As far as I’m concerned, this is the pinnacle of dining out — conspiratorial, communal. Ballet.

I can feel Si Newhouse’s assprint beneath my cheeks, the assorted perfumes of Rupert Murdoch’s various wives wafting past.

The girls rattle off the other MFG restaurants they’ve notched. By now, Frank Sinatra is roaring. The music is a little obvious, I suggest to our new companions. “I wish they’d play more Drake,” one says. This is not what I wish for this restaurant, but it is a telling demand for placelessness. Did they ever see celebs at Torrisi? “We were there a lot and never saw anyone but Woody Allen.”

The sommelier splits our next bottle between us and the girls, as generous and convivial a gesture I’ve ever experienced in a restaurant. Focaccia. The famous spicy rigatoni vodka. The famous $89 veal parm. More pastas. The famous meatballs. Dover piccata. Ribeye Diana. I don’t remember what we ordered and what was bestowed upon us. I begin to focus on my stomach — ballooning, churning, expanding — and think of the syringe they use on cows to release methane from their cavernous insides. I’m being fattened like a Christmas goose, doted on and sadistically overstuffed in short order. I don’t see any stars in the room, so maybe I am the celebrity tonight. A beacon of media glamour, performing my best Craig Claiborne for people who have likely never heard of him.

IV. ZZ’s Club: You Can’t Sit With Us

A week later, I’m due at ZZ’s Club, The Boys’ member-only restaurant complex in Hudson Yards that costs $20,000 to join, plus an additional $10,000 annual fee. Plus the cost of rigatoni. I hurry past the Backyard at Hudson Yards summer stage Presented by Wells Fargo Powered by Verizon before reaching the ZZ’s lobby, where the four friends I’ve been generously permitted to invite and I are greeted by an exceedingly eager floor manager. “This is my favorite room!” he gushes as we enter a sushi restaurant.

Upstairs, Lauren, the publicity guru and sherpa of my culinary journey, is waiting for us, emitting the glamor I would expect from a Miami-based PR maven — midriff-baring professional top, wide creme pants, healthy tan. The manager and Lauren continue our tour through a warren of exclusive fabric-laden enclosures, starting with the Founders’ Room, which costs $50,000 to join. Founders enjoy the privilege of ordering anything they want from the kitchen, given 48 hours’ notice. In the Living Room, our tour guides turn our attention to a marble bar. It’s not actually marble, he explains, but is painted to resemble marble. We ooh and ah over a technique I have seen on budget home reno TikToks, singing for our supper. That the emulation of marble would be more impressive than marble itself is only true if you value performance over reality — the artisan’s sleight of hand, triumphing over nature. A scrappiness that keeps asserting itself in The Boys’ story. Everyone doubted us. Everyone (still) wants us to fail. Nevertheless, we sold $89 veal parm. Nevertheless, we made you believe wood was marble.

“I love commitment to the bit, and I love when people have a budget and they do something with it,” Alison Roman says.

The final velvet enclave is Carbone Privato. “It’s the only Carbone in the world with a modified menu,” the floor manager whispers, as if we’ve entered a UNESCO heritage site. One such modification includes a lobster risotto; Mario has bragged he refuses to put risotto on a menu because, if made to order, it takes too long. True to legend, on the menu below the lobster risotto ($150), it reads “please allow 40 minutes.” Tableside preparations shift into overdrive. The evening is a festival of trolleys, including a flambéed cherry dessert, and the “Less Than Zero” martini. Our martini-ist tells us the liquor is chilled to -40 degrees. Like a juggler at a child’s birthday party, from several feet above the glass she pours the correct amount of vermouth without the aid of a jigger, along with the gin (Monkey 47, the only option if someone else is paying). It is cold. Throughout the meal, which is fabulous, servers reveal each ingredient conspiratorially (the pink lemons? From California).

When the risotto arrives promptly at the 40-minute mark, it is presented first for photogenic appraisal, the lobster half-submerged in his shallow grave of rice, claws hanging over the lip of the gold terrine, as if he was trying to escape and gave up. Instragams captured, the platter is whisked away and the shells removed for a more frictionless eating experience. There is no easy way to say this, but the rice was undercooked. I understand Mario’s concern. Perhaps it should’ve said the 50-minute risotto.

Most of the diners here look like Ivanka Trump, that is to say, modern Palm Beach Republicans with nose jobs, who take hair gummies and have gay friends. The room feels rich, but certainly not a $20,000 bacchanal. Why is no one smoking a cigar? And where is the cocaine? Mario, my brother bound in butter, a responsible hedonist with his eye on the bottom line, just wants to sling his pasta and go. Was it always this transactional? I need to talk to someone who was there in the glory days.

Jay McInerney tells me he’ll call me back when he’s done with his trainer (he’s in Los Angeles, of course). The ’80s enfant terrible and author of Bright Lights, Big City, which features The Odeon on its cover, was a literary poster boy for a level of glammed-up debauchery ZZ’s Club can only dream of. “I had a friend from the Midwest who was one of the first waitresses at Indochine,” McInerney tells me after his lunges, “and she couldn’t understand why all the food was coming back, and why we were all crowded around this single bathroom.” And yet, no one was dropping even the 1984 equivalent of $89 on veal parm back then. “The idea of being a foodie and doing coke at a restaurant are kind of antithetical, right? It really was more social in those early years than it was culinary. The food [at the Odeon] was good enough, but the restaurant was just incredibly sexy. Fine dining was an uptown pursuit. It didn’t interest hipsters.” Now of course the hipsters are foodies. Although not quite in the Carbone empire. As Jay concedes, “veal parm is not a connoisseur’s dish.”

I think of ZZ’s lobster throwing in the towel on his escape plans, looking around at the obscene wealth, the Apple Watches. It’s like Rome, for optimizers. The empire is fading — America’s or The Boys’? Either way, we might as well party; the fintech bros are taking whatever isn’t nailed down, and really, can you blame them? We all just want to be served martinis or Caesar salads or both, at any cost, from a sliding trolley. “There was this really exemplary restaurant called Elaine’s,” Jay says, referring to the uptown 1980s mainstay. “The way Elaine managed the crowd — she would put the tourists in the back room, and up front would be Hollywood figures, literary figures, and sports figures. And, you know, I think one of the reasons I liked it was because so many writers went there, right? Elaine liked the writers.”

I’m a writer. I also love restaurants. I do not want to see them prostituted on TikTok and dehumanized via Resy. But if Elaine, or The Boys, or anyone really, can seat me at a corner booth, view of the entire room, if the choreography is ambitious, the arabesques taut, the movements coursed out with charm and wit, then I will gladly sing for my supper.