Books

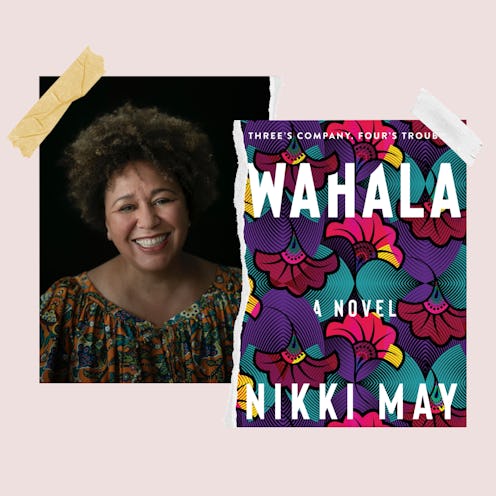

In Nikki May’s Debut Novel, “Sh*t Happens Everywhere”

Two Anglo-Nigerian women learn of a friend’s traumatic incident in an excerpt from May’s Wahala.

In this section excerpted from Nikki May’s debut novel, Wahala, two Anglo-Nigerian friends — Fifi and Boo — hear about their Aunty K’s close brush with death.

Fifi opened the door. “Akwaaba. Sister Ronke, you are welcome. Please enter.”

“Hey, Fifi.” Ronke pushed Boo through the open door.

“Hello, ma, you are welcome, ma. Please come and sit, ma.”

An hour later, Ronke was eating kelewele – soft plantains fried in palm oil with peppers, ginger and garlic, having her usual deep- conditioning hot-oil treatment. Her hair was covered in thick greasy moisturizer, piled up on her head and wrapped in a plastic cap. Rivulets of oil had escaped and dribbled down her face and neck. Ronke was supposed to stay under the steamer hood – the heat made the conditioner penetrate – but it got in the way of eating and talking.

Boo picked at a tub of jollof rice. She’d chosen it despite Ronke’s hushed warning (she didn’t want Fifi to hear) that Ghanaian jollof was not a patch on Nigerian jollof. Fifi had finished cornrowing Boo’s hair – step one in the weave process.

“Did I tell you what happened to Aunty K last weekend?” Ronke asked. She knew she hadn’t, but she wanted to start this story casually.

“No. What?” Boo turned to face Ronke.

“Keep your head straight, ma!” said Fifi. “I am holding big needle, ehn.”

“Please don’t call me ma,” said Boo for the fourth time.

“I’m sorry, ma,” said Fifi.

“It’s going to be one big ’fro,” said Ronke. Boo’s hair was now a spiral of cornrows snaking round her head. Fifi was stitching on hair extensions, wefts of frizzy brown and blond hair.

“I look like a mollusk,” said Boo.

“The braids should be tighter, ehn,” said Fifi. “This is not lasting a long time, ma.”

“It’s tight enough.” Boo peered in the mirror. “I look like I’ve had a facelift. I think it might be too long, I don’t want to be Chaka Khan.”

“I’m cutting it after, ma.” Fifi muted the sound on the TV. “Sister Ronke, you are telling us about your aunty.”

She pronounced it “anti.” It made Ronke feel homesick. In Nigeria everyone older than you was an anti or an uncoo.

“It was terrible. She’d only been home for two weeks when it happened,” said Ronke. She ate the last piece of kelewele and wiped her hands on a napkin.

She’d heard the story three times now, first from Uncle Joseph, then Aunty K herself and finally her cousin, Obi. And she’d told it three times. To Rafa, Kayode and Kayode’s sister, Yetty. It got more exaggerated with each retelling. She spun her chair round so she was more central, then decided standing would be more dramatic. This was proper Naija gist – it had to be told the right way. In a loud voice and with lavish gestures.

“It was a regular Sunday,” Ronke began. “Aunty K had been to Lagos for the weekend. After church, she set off for home – an easy two- hour drive. Aunty K is always careful, she never uses the expressway at night, doesn’t venture out after dark. She keeps the doors locked and windows wound up. And all her valuables – even her wedding ring – were stashed in her handbag, hidden in the footwell. She’d even put her dummy bag on the passenger seat.”

“What’s a dummy bag?” asked Boo.

“A cheap bag to fool the robbers, standard practice in Lagos. Aunty K has a set of keys, a broken phone and some old makeup in hers. It’s a decoy – if you get carjacked, the thieves snatch it and run. By the time they find out, fingers crossed, you’re miles away.”

“Bloody hell,” said Boo.

“Lord, in your mercy, protect us.” Fifi touched her hand to her forehead, chest and shoulders.

Ronke paused, worried Fifi would stab herself with the big needle. Once Fifi was safe from puncture wounds, she resumed.

“Now, Aunty K isn’t rich and her car isn’t flashy. We’re talking dusty five-year-old Toyota Sienna. No leather seats, no air-con, no central locking. A standard tokumbo.”

“Tokumbo?” Boo stumbled over the word.

“A used car – you know, secondhand.” Ronke had got so carried away with her story, she’d forgotten how little Boo knew about life in Nigeria. “It means from across the sea – an import.”

By this point, Fifi had stopped working on Boo’s hair, the comb and needle abandoned. She held one hand up to her face, a stricken but eager expression on it. Even Boo looked spellbound, if a little odd with a quarter of an Afro. Ronke turned her voice up a notch.

“So, Aunty K’s on the expressway, singing along to her church program, thinking about supper. She was pretty sure she had some edikaikong soup in the freezer. Then out of nowhere, a car zooms up beside her and forces her off the road onto the hard shoulder. This is Nigeria, Boo, so the hard shoulder is not a safe haven. It’s pot-holed and full of crap – old burst tires, burned-out cars. You don’t know what’s lurking there. Or who.”

“Oh, my sweet Jesus.” Fifi crossed herself again.

“Bloody hell,” whispered Boo.

“Aunty K is trembling like a leaf, cursing the idiot who ran her off the road. The church music is still blaring out on the radio, she’s taking deep breaths. CRASH!” Ronke clapped her hands together. Fifi and Boo jumped gratifyingly.

“The driver’s-side window explodes,” Ronke continued. “A shower of tiny shards of glass rains down. Aunty K thinks it’s a bomb. Rough hands yank her out of the car. Someone is shouting but she has no idea what he’s saying. She’s thrown down onto the hot filthy tarmac. Three men are leaning over her; they have machetes in their hands. Her wrapper is pulled open. She knows this is the end. She’s going to be raped and murdered.”

“Pray God, save our aunty,” breathed Fifi.

“Bloody hell,” said Boo.

“Then God speaks to Aunty K. He tells her to sing. To sing for her life.” Ronke realized she’d gone a bit RuPaul on the last line – Rafa’s influence. “So, she closes her eyes, crosses her hands around her chest and bellows at the top of her voice.”

The God-speaking hadn’t actually happened. Ronke had added that bit for Fifi’s benefit. She considered lying on the floor, doing a full arms-crossed impression, but the salon was dirty. She sang, aiming for soprano, improvising as she didn’t know the tune. “Save me, Jesus, Save me, Jesus, From this godforsaken place.” Ronke paused to ramp up the tension.

“Then what?” said Boo.

“Sweet holy Jesus,” said Fifi.

“The next thing she hears is a sweet, soft voice asking if she’s OK. Aunty K opens her eyes and there’s a beautiful woman dressed in white – an angel – kneeling beside her and telling her she’s safe. Turns out the thieves were scared of God and they scarpered. A passing car had seen it all and rushed to help. The driver of that car was the angel – a nurse in uniform. She picked Aunty K up, dusted her down, and gave her an escort all the way home to Ibadan.”

“Onyame ye! God is truly wonderful. He works in mysterious ways,” said Fifi.

“That’s it. I am never going to Nigeria,” said Boo.

“Shit happens everywhere,” said Ronke.

From the book WAHALA by Nikki May. Copyright © 2022 by T-Unit Books Ltd. To be published on January 11, 2022 by Custom House, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.