Books

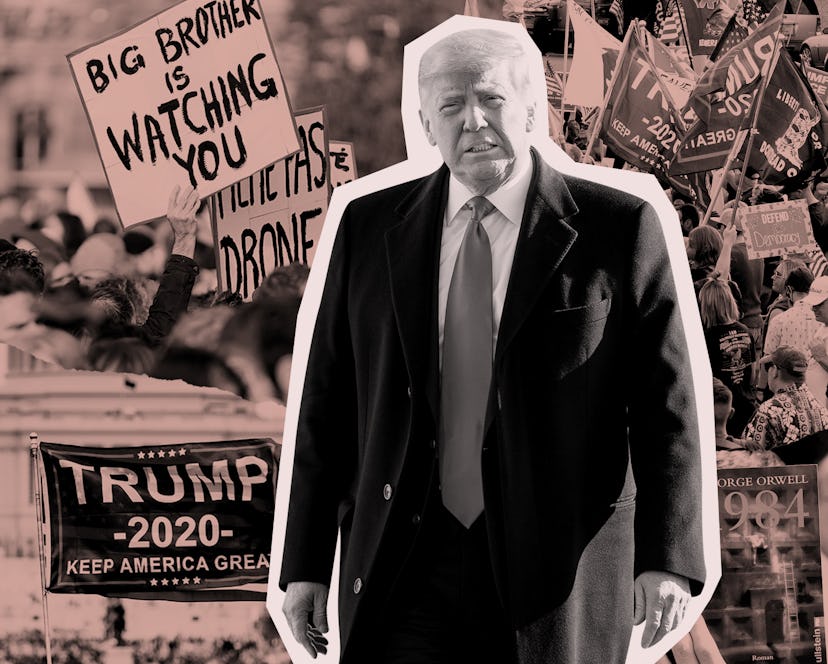

Trump’s Cronies Should Be Reading Kazuo Ishiguro, Not George Orwell

They've got the wrong literary blueprint.

If you’ve had the misfortunate of stumbling across a (nonbanned) social media account from one of Trump’s ilk this weekend, you’ve probably seen the word “Orwellian.” If you need it in a sentence, it's “Banning Trump from Twitter is Orwellian!!!” or “It is positively Orwellian for a private company to hold a person accountable for their actions!” or “I am using the word ‘Orwellian’ because I think it sounds smart so I can disguise the fact that the actual content of my point is morally and intellectually hollow!”

I have to imagine their first-rate literary analysis comes from having once partially overheard a drunk person describe the plot of Nineteen-Eighty-Four because what’s happening to Trump and his most craven supporters on social media is not “Orwellian.” Ignoring the fact that George Orwell was an explicit democratic socialist, Nineteen-Eighty-Four is about a totalitarian governmental regime that freely lies and distorts facts to serve its purpose, with a cult-of-personality around a central leader. I admit it’s been a while since I read the book in middle school, but I don’t remember the scene where the narrator has his Twitter account deleted because he tried to encourage an armed insurrection to subvert a democratic election.

As the sea change in our country slowly (slowly) begins to create an atmosphere in which the rats are jumping ship and Trump and his associates might face the tiniest consequences for their actions, it’s obvious to me that what’s happening isn’t out of Nineteen-Eighty-Four. It’s a narrative told in the brilliant 1986 novel An Artist of the Floating World by Nobel Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro.

In fantasy movies and books, sometimes when the hero defeats the Big Bad, his minions all disappear at once in a puff of smoke. Reality is never that tidy.

Ishiguro is probably better known for Never Let Me Go and The Remains of the Day, both of which were adapted into films, but both of which owe some of their DNA to An Artist of the Floating World, an earlier book in which the writer mastered the art of the melancholy first-person narrator.

The book takes place in Japan after World War II and the fall of the country’s imperialist regime. It’s narrated by a man named Masuji Ono, a once-prominent painter who has aged into obscurity verging on disgrace because — as the novel slowly reveals — Ono had turned his artistic ability toward making totalitarian propaganda. As in The Remains of the Day, the reader is forced to read between the lines, in the subtext and in the reactions of the people around and to the narrator, because the narrator is unwilling to admit certain truths, even to himself. Though early in the book it seems as though Ono might understand and feel guilty for what he enabled, by the final chapters, he’s set in his ways, content with a flimsy narrative of his own goodness and unwilling to fully reckon with the pain and damage he caused to his country.

An Artist of the Floating World denies the reader the catharsis of bad actors actually taking responsibility for their own actions.

In fantasy movies and books, sometimes when the hero defeats the Big Bad, his minions all disappear at once in a puff of smoke. Reality is never that tidy. Evil has administrators, the mid-level bureaucrats who justify their own misdeeds and vacuum-seal away any feelings that might eventually coalesce into guiltiness. An Artist of the Floating World is tragic, not only for its main character, who grows more isolated from his children and community and yet remains unwilling to reckon with why, but it also denies the reader the catharsis of bad actors actually taking responsibility for their own actions.

I fully admit: I cannot be the monk-like person I wish I was, the beacon of benevolence who takes no pleasure in Trump-supporting domestic terrorists melting down because they were put on the do-not-fly list. But those types of punishments are enjoyable in the schadenfreude they deliver in the moment — I want to know that these people, the cronies who enabled and supported Trump at every step of the way for their own selfish ends, might eventually find a reckoning within the mirror. I know that’s impossible to ask for, but that’s the punishment I so desperately want for them, and the one Ishiguro recognizes is almost impossible to come by.

And so, to the Trump supporters looking for the literary blueprint to what their future holds, I think An Artist of the Floating World is the best possible choice, a small, domestic book that articulates the big themes about the enablers who just go on to quietly live their lives, telling themselves whatever they need to to get through another day.

In Just Why, Dana Schwartz examines the strange and sublime pop culture moments being discussed on the internet this week.