Entertainment

This New True Crime Doc Is A Terrifying Look At A Serial Killer Who Targeted Young Black Women

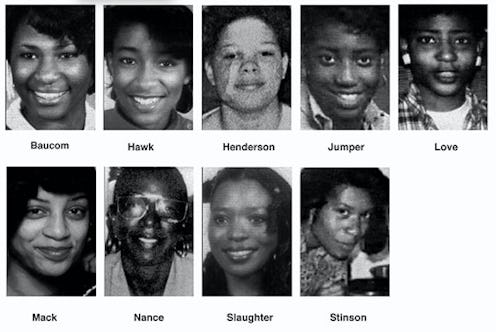

Recent shows and podcasts like NPR's Serial and Netflix's Making a Murderer may have reignited the current obsession with true crime, but one network has been on the case for over two decades. The Investigation Discovery channel has magnified some of the most interesting, terrifying, and mysterious true crime stories since 1996, and its latest true crime documentary special, Bad Henry, is no different. The doc, which airs on July 24 at 9 p.m, tackles the chilling story of Henry Louis Wallace, who murdered 10 African-American women over a two year-span in the '90s before being caught. Yet while Bad Henry questions the reasons it took law enforcement so long to capture Wallace, for one victim's mother, the answer is obvious.

"It was obvious that they took too long on purpose," says Dee Sumpter, whose daughter, Shawna Hawk, was one of Wallace's victims. Speaking over the phone in July, Sumpter asserts that because Wallace's victims were poor and black, their cases weren't handled with the same urgency that white victims often receive. In Sumpter's eyes, "had Shawna been white or of a different higher level, economically speaking, then on the night of her murder, several persons would have been locked up... as opposed to no one."

In the early '90s, Charlotte, North Carolina was still feeling the effects of America's crack epidemic of the 1980s. Murders were on the rise, and the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department's resources were spread thin. One by one, young, poor, black women were going missing or were found strangled to death with little media attention focusing on the similarities in their cases. But as Garry McFadden, CMPD's only black detective in the homicide division, eventually figured out, Wallace — unlike most serial killers — was targeting women he knew. He even brazenly attended the funerals and memorial services for his own victims.

"Henry was standing across the street from our home watching the investigation unfold," Sumpter notes. "He even saw them wheeling her body out on a gurney that night. He was bold enough to come to her funeral. He signed in at one of the wake’s that he attended. This is the level, or should I say lack of, investigation that was going on."

To Sumpter, the connection between her daughter and the other young, black women who were dying was crystal clear, even if the detectives didn't figure it out until much later. As Sumpter recalls, during a press conference, when one reporter pointed out that all of the mysterious deaths shared strikingly similar details, the detectives bristled. "When it became obvious what was going on, I began to approach the homicide folks and [said], 'Do you not see what I see here? These are African-American women, clearly blue collar women and yet you’re not bothering to make a phone call,'" Sumpter says now.

Bad Henry addresses the fact that Wallace's victims weren't getting the media attention that, in hindsight, the investigators admit they deserved. But Sumpter's commentary highlights an inherent bias when it comes to the way crimes committed against black women are investigated. As the Institute for Women's Policy Research points out, a 2015 study shows that black women are two and a half times more likely to be murdered by men than white women, yet there's often much less coverage of black women's cases than those of white women. Late PBS journalist Gwen Ifill even dubbed the phenomenon "Missing White Woman Syndrome," criticizing how the media frequently seems disinterested in covering cases involving people of color.

Sumpter is taking the issue into her own hands. The lack of support and the large number of families who've lost their daughters during those years in Charlotte — as well as her own need for an outlet to heal — inspired her to start MoM-O, Mothers of Murdered Offspring. The support group directs the families of murdered victims to resources, information, and aid. "It made sense to me that if we can have alcoholic anonymous, narcotics anonymous, overeaters anonymous, on and on and on, why don’t we have something in place that tends to murder? Because it happens everyday," Sumpter explains. "We cannot sit idly by and allow the stench of the blood of our murdered children to flow freely through the streets of Charlotte, and who better than us as their mothers to speak this for them?"

Sumpter adds that she sees the public's interest in true crime entertainment as a positive addition to her cause. She actually hopes to one day make a narrative film about Shawna and Wallace's other victims. Says Sumpter, "I’ve never tired of being able to say how much I loved Shawna and how much her love of me has affected me and fueled me. It was because of her that I want to share this love with everyone else." And so she is, in an incredibly powerful way.