Culture

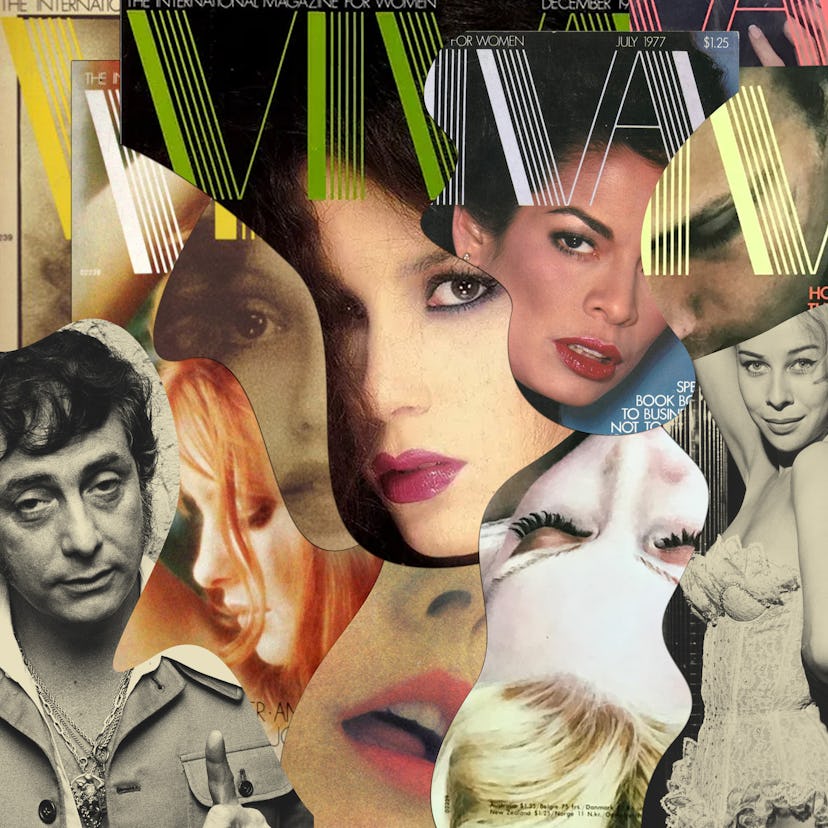

The Hot Rise & Depressing Fall Of A 1970s Feminist Porn Magazine

The inside story of the publication that Anna Wintour briefly called home.

It’s hot. Two nude hippies — their toned bodies tanned from the sun — languidly stroll on a pebbly beach. Walking away from the camera, this golden couple look like they’re on their way to have sex in the rough. Walking away from the camera, they each rest a tanned hand over the other’s bare derrière.

This is the cover of the July 1974 edition of Viva — a feminist porn magazine that ran from October 1973 to January 1979. Viva featured stories on bisexuality and sex-worker issues, models sensuously draped in sheer chiffon, and arty male nudes shot by women photographers. Simone de Beauvoir, Joyce Carol Oates, and Nikki Giovanni all wrote for it. Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison were interviewed. John Lennon and Paul Newman posed for its pages (clothed). Anna Wintour did its fashion spreads at one point.

“It was so beautiful, so high-end, and really progressive sexually,” says journalist Jennifer Romolini.

Romolini first came across it while searching for vintage prairie dresses on eBay in the early 2000s. Intrigued, she bought her first issue — the one with the naked couple on the beach. She had never seen anything like it in her years working at women’s magazines.

“It wasn't self-serious like Ms., but it also treated the readers like they were substantive,” she says. “And there was real journalism in it — and then of course, all these naked penises.”

Even more shocking: Viva was published by Bob Guccione, the flamboyant, perpetually open-shirted, gold-chain-laden porn mogul behind the men’s magazine Penthouse. What made him want to publish a magazine for women? And how did its largely female staff manage to make it so… good?

Romolini is now telling that story. Her new eight-episode podcast Stiffed, a weekly co-production of iHeartPodcasts and Crooked Media, launched on March 30. It charts the rise and fall of Viva, one of America’s first women’s porn magazines.

“There are very few times that women have been allowed to bring our lens to bear on human sexuality,” Romolini says. Stiffed looks at what happens when — or if — women are able to do so.

“I think the idea was to counter the idea that feminists were all the sort of dried-up prudes that couldn't get a date — that they could be sexy too,” says Molly Haskell, Viva’s film critic. “Bob Guccione — I mean, he was no great suffragette, but he did want to do this.”

Guccione started Penthouse in 1965 while living in London, as a more sexually explicit competitor to Playboy. (He told one interviewer that he considered the “pubis” the “most beautiful part of a woman’s body” and thought the rest of the world should agree with him.) The scrappy Brooklyn native — an aspiring artist who went to Europe to study painting — shot many of Penthouse’s early centerfolds himself, developing the magazine’s soft, dreamy aesthetic by smearing his camera lens with Vaseline.

“He was a really fascinating character,” says Romolini. “He loved women and lauded them, and [yet] he was still a product of his time, which was super misogynistic. But he was also daring and courageous and experimental and very open-minded.”

Guccione was one of the only magazine moguls who hired women and gave them good wages, too. He convinced Kathy Keeton — the highest-paid stripper in Britain — to sell ads for Penthouse. (She later became his third wife.) And he tapped another woman, the young British journalist Gay Bryant, to run the American version of Penthouse in 1969.

It was Bryant who first had the idea of creating a Penthouse for women.

“I began to think, ‘Gee, you know, why can’t women who are now part of the sexual revolution and the women’s women and so on — why can’t they have a magazine like this for them?’” Bryant told Romolini on Stiffed. She wrote a 50-page proposal in 1973 for an erotic women’s magazine. Viva debuted that October, though Guccione claimed that it was his idea.

Viva said: ‘Enjoy sex. Enjoy being a woman; enjoy your body; enjoy sensuality.’

“[Guccione] was brilliant in so many ways, but he was also cocky,” Romolini says. “He just thought, ‘Well, how different could it be to put out a magazine for women?’”

Quite different. Though Penthouse did have its share of muckraking journalism and celebrity interviews, it wasn’t like Playboy; guys did not buy Penthouse for the articles. Viva always had more writing interspersed with its porny pictorials, including cultural reporting and criticism. Yet its first issue suffered from Guccione’s excessively macho point of view. It had an interview with tough-guy Norman Mailer, a lewd cartoon called “The Little Hooker,” and a “wearable art” fashion shoot that featured a surprising amount of vulvas and bare breasts for a magazine ostensibly for straight women.

“Guccione kept barging in like a bull in a china shop, making it weird,” Viva columnist Annie Gottlieb told Romolini on Stiffed. “It was annoying — and funny.”

“We knew who we were working for, and we did not let it stifle us,” Viva senior editor Bette-Jane Raphael said on Stiffed — adding that she and her colleagues began publishing “Graffiti,” a nonglossy feminist insert within the publication. “I would just go after people I wanted to see in the magazine. We just did our stories, our articles, and then had them put together with photo layouts of softcore porn.”

Eventually, Keeton took over as editor-in-chief, and Guccione mostly let a new staff of women — including Gottlieb, Raphael, Newsweek alumnus Patricia Lynden, and writer and eventual editor Robin Wolaner — run whatever they wanted, from a report on sex workers trying to unionize to a feature on female rodeo writers.

“I don’t think he read anything,” says Haskell, who also wrote for the Village Voice and Ms. “I remember doing a piece about not having children, and that’s where I think it was really ahead of its time, even [looking at it] today.”

“It was fun,” says Judy Kuriansky, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist and professor at Columbia who wrote Viva’s sex-advice column. “Writing for a platform like that, you’re unafraid to express what people are really feeling without couching things in very politically correct terminology.” Plus, “it was the only thing like it at the time devoted to women.”

Viva shared offices with Penthouse in Manhattan, where execs had vulva-shaped ashtrays and buzzed their secretaries with a nipple-shaped button.

Wolaner — who started working as a secretary for Penthouse at 17 and later founded Parenting magazine — told Romolini, “We were going to be the intelligent women’s Cosmo.”

“Viva was unique, because it acknowledged women as sexual beings,” says fashion and cultural historian Laura McLaws Helms, author of the newsletter Sighs and Whispers. Even when Helen Gurley Brown took over Cosmopolitan in 1965 and made it more about sex, it was very much tied to getting a man, McLaws Helms points out. “Cosmo was: ‘How do you dress to get a man? What do you do in bed once you get the man? What do you cook for that man?’ Even if it was talking about being a single woman, it’s like, ‘how do you enjoy your life until you find a man?’ Viva said: ‘Enjoy sex. Enjoy being a woman; enjoy your body; enjoy sensuality.’”

Still, it was an odd place to work. Viva shared offices with Penthouse in Manhattan, where execs had vulva-shaped ashtrays and buzzed their secretaries with a nipple-shaped button. Guccione almost never went to the office but held late-night editorial meetings at his mansion, which housed a dormitory for a rotating cast of Penthouse Pets upstairs. His fleet of Rhodesian ridgebacks ran around the table barking as the staff discussed editorial strategy till 2 a.m.

Guccione may not have dictated the magazine’s text — though Romolini hints that he did fire an editor for publishing something too “feminist” (which she will explore in a future episode) — but he did have a hand in the art direction. He came up with Viva’s most notorious spread: a “pubic hairstyles” shoot styled by famed hairdresser Paul Mitchell.

“I’ll never forget the ‘pubic hairstyles’ run-through in the conference room, which took place about the time Nixon was accused of impeding the Watergate break-in investigation,” Hollywood biographer and former Viva editor Patricia Bosworth later wrote in Vanity Fair. “It was surreal watching hookers and porn stars flipping up their skirts while Bob sketched outlandish drawings of Nixon as Judas.”

“You have to remember that this is the 1970s,” Romolini says. “Deep Throat was in the Top 10 box office hits [of 1972]; porn is everywhere. It was edgy, cool, kind of avant-garde.” The outré content didn’t scare off big-name cover stars like Bianca Jagger or interviewees like Elliott Gould or James Caan. “Getting celebrities [for the magazine] was not a problem because porn was cool.”

The problem was getting advertisers. While electronics or alcohol brands didn’t mind having their products hawked in Penthouse, cosmetics companies like Maybelline or Revlon didn’t want their makeup featured alongside pictures of naked men on horseback or a couple doing it in the kitchen — no matter how beautifully or cleverly shot. By 1977, Viva stopped doing full-frontal shots. It hired Wintour, who had just been fired from Harper’s Bazaar, to class up its fashion pages. That turned off some gay men, who made up a big chunk of the magazine’s subscriber base, and it didn’t do much to lure in new readers (or advertisers) either. Guccione and Keeton kept going through different editors with drastically different visions. In the end, Viva resembled a conventional women’s magazine. Its last issue, January 1979, included a feature on how to fight cellulite.

“I think it failed because people weren't ready for it,” Romolini says. “We weren't ready to see women liberated sexually, professionally, personally.”

And maybe we still aren’t. Fifty years after Viva’s debut, American women are still fighting for autonomy over their own bodies, for equal pay and opportunities. We’re still arguing about what feminism looks like (and who it includes) and whether porn is bad or good. Viva, despite some of its cringier elements, still looks revolutionary, daring, and hopeful. It provides a glimpse of what could be possible when women work together to create something honest and beautiful, against all odds.

Rather than a tale about an X-rated mogul’s failed attempt to launch a women’s erotic magazine, Stiffed paints a different picture. “It’s a story about a group of women working together and putting their best effort into something,” Romolini says. “I just wanted to tell their stories and do right by them.”

This article was originally published on