Exclusive

Am I An Influencer Yet?

In both my acting career and on Instagram, I’ve felt an uncomfortable pressure to sell sex to get ahead. Could doing drag set me free?

When I was 18 and playing a “good girl” character on a network family drama, I had dinner at a swanky West Hollywood steakhouse with my favorite agent. As we discussed the future of my career, he suggested, “One day, you might want to do a sexy photo shoot to change the way people see you.” Surprised and uncomfortable, I scoffed. Undeterred, he clarified, “I’m serious.”

This was far from the first time someone decades older than me had made a veiled comment implying that sexualizing myself might help me professionally. I’d been acting since I was 10, and as I grew up, I rebelled by hiding my body and getting unflattering haircuts before it was cool. In the era of sexy shows like Gossip Girl, my please-don’t-look-at-my-body aesthetic didn’t make me a natural ingenue. Years later, though, over quarantine, I finally found an outlet for performance that didn’t rely on selling sex: I made Quaranscenes, a social media video series in which I reenact scenes from iconic movies and TV shows while wearing sloppily self-styled wigs and cheap costumes.

Making online videos meant being on social media a lot. As I navigated a sea of beautiful photos of actors, models, influencers, and the women who just look like them, I felt that old, familiar, amorphous pressure to sell sex wash over me again. I noticed one photo in particular, posted by a comedian I’d followed on Instagram for years. Her hair was longer and thicker, her lips were bigger and poutier, and her skin glowed. She looked like a Kardashian, not the stand-up who formerly graced my feed. She had the “distinctly white but ethnically ambiguous... single cyborgian face” that Jia Tolentino dubbed Instagram Face in The New Yorker. Days later, when I was borrowing a wig for a Quaranscene from my friend and hairstylist Eddie Cook, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I suggested we style me as a Kardashian-esque influencer for a photo shoot. After voicing concern that I would develop body dysmorphia, he agreed.

So I sought out inspiration, using the grids of the most famous Instagram Faces — Emily Ratajkowski, Kim Kardashian and her family — as my blueprint. But I quickly realized there was a problem, and it was my body. I didn’t have crystal ball-sized boobs, hourglass hips, or a thigh gap. To achieve that, I thought, I’d need major surgery. Then I had a better idea.

My one standing quarantine social tradition was a weekly Zoom viewing party of RuPaul’s Drag Race, watching people named Thomas, Roger, Kevin, Cade, Reggie, Jared, and Cody transform into Bimini Bon-Boulash, Tayce, Kandy Muse, Gottmik, Symone, Jaida Essence Hall, and Crystal Methyd. How many times had I watched queens give themselves instantly exaggerated hourglass shapes just by using removable rubber breast plates and butt pads? If I wanted Instagram Body, I could just do drag. I could become a whole new person, one who transcends my fears and is named after a 2000s pop star. I could be Successica.

Twelve years after that dinner with my agent, I finally did a sexy photo shoot. I just don’t think this is what he had in mind.

Step 1: Hair Done, Face Beat

Growing up in a pre-Instagram Face era, I idealized a type of no-makeup “natural” beauty, aka beauty that just existed without effort or care. Trying to be beautiful meant courting attention, which felt terrifying. Better to just be so innately beautiful that suitors and opportunities would throw themselves at me while I was reading a book on a park bench. (Think teenage Rory Gilmore, and… that’s pretty much it.) According to RuPaul, “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag,” so I was unknowingly serving Pretty But Doesn’t Know It, aka Troublingly Low Self-Esteem.

Drag Race, meanwhile, is about intentionally crafting your appearance — whether it’s gorgeous, otherworldly, or Muppet. It catalogues the queens’ extravagant transformations — covering their stubble with color-correcting red paint and drawing on eyebrows while wearing wig caps — before they Ru-veal their final looks to the judges. When they’re critiqued, even RuPaul’s and Michelle Visage’s harshest notes feel directed at the execution of a concept, a performance, a persona, an artwork. The queens’ essence, worth, and beauty as human beings is never called into question. This, sadly, felt revelatory.

Eddie told me that looking like an influencer required as much work as looking like a drag queen, so I hired makeup artist Auður Jónsdóttir to contour my face. I was going for an over-the-top, more-is-more look, so after 1.5 hours of face painting, I was shocked to look into my iPhone camera and find myself still looking like myself, only much better. I confidently fired off selfies, exhilarated and wishing I could look like this every day. I had Instagram Face and, honey, it felt good. This, Eddie told me as he snapped “Hair Peace” clip-on extensions to my scalp, was what he’d warned me about.

Step 2: Body-ody-ody

My breastplate arrived in a plastic bag. Pulling the pale, rubber suit over my neck felt claustrophobic. But once I had it on, I marveled at the reflection of my D-cups in the mirror. I looked naked but was covered up. I felt safe.

When I told my therapist about this shoot, she reminded me that years ago, I’d come to her enraged after reading the essay “Baby Woman” by Emily Ratajkowski, a self-described “archetypal multi-hyphenate celebrity.” Ratajkowski wrote about how her healthy upbringing with Atticus Finch-type parents had given her the security to feel empowered posing naked. I thought I was mad that Ratajkowski enjoyed catering to a faceless male audience. My therapist clarified that beneath my rage was grief, for a sense of safety I’d never had as a child actor with parents who were loving but not out of To Kill a Mockingbird. When I was a teenager, my dad made dating seem dangerous while my mom suggested I wear shorter, tighter outfits to auditions. The mixed messages and expectation to perform sexuality sent me into a prolonged, overwhelming state of freeze, which neither media executives nor high schoolers were super interested in. So when Ratajkowski claimed she enjoyed sexualizing herself, I reflexively took it as further confirmation that there was something wrong with me for being such a buzzkill.

Then a few years ago, I started watching Drag Race and was introduced to a whole new world of possibility. Week after week, contestants shared heart-wrenching personal stories before serving sex-art-diva-glam on the runway. Some of the queens grew up with parents who shamed them. Some didn’t identify with society’s expectations, so they struggled with feeling lonely, misunderstood, and ashamed. We didn’t go through the same circumstances, but I related to their pain and admired their courage to unpack and share their experiences. Watching them transcend trauma and express themselves via outrageous drag characters was healing and freeing.

While wearing the breastplate, butt pads, and opaque leggings, showing as much “skin” as possible in the Bratz doll-like clothes my stylist Amanda Massi pulled for me suddenly felt fun. Still, the morning of the shoot, I panicked. What if, even with all these layers of tits and ass, I wasn’t sexy? What if people who saw the photos felt embarrassed for me, or worse, got bored and looked away? Suddenly I felt like a young actor auditioning for the approval of a casting director, producer, director, agent, whoever. This, I reminded myself, wasn’t an audition. This was drag.

Step 3: BTS Secret Project

Eddie told me that celebrity influencers frequently shared “behind the scenes” shots of “secret projects,” so I did too. Before posting, I scrolled through Kylie Jenner’s feed one last time to make sure I’d gotten everything right. I’d given myself the hair, makeup, body, and clothes, so I was disappointed to feel like something was still missing. These photos, I belatedly realized, must be edited.

How could I have forgotten about editing? I knew about Celebface, the Instagram account that exposes celebrity photo retouching. I knew that Instagram Face was the result of plastic surgery and the photo editing app Facetune. Despite my fake hair, fake boobs, fake ass, and heavily painted face, my photos weren’t aspirational enough. They looked too human.

So I asked the photographer, Kelsey Hale, to edit my face. Using the Photoshop “liquify” tool, she quickly reduced the size of my forehead and subtly adjusted my jaw. I was disappointed that my lips, which I’d never felt insecure about before, didn’t look as evenly plump as Kylie’s, Emily’s, or Kim’s. So Kelsey enlarged and mirrored them to be literally symmetrical, though they still looked uneven to my stupid human eye. The Photoshop was so believable, I had to toggle back and forth between before and after photos to notice most of the changes. Before I posted the shot, Kelsey warned me I might get some blowback, but the opposite was true.

Friends of mine commented variations of “holy f*ck” and “holy sh*t,” fire emojis, and heart eyes. My mother-in-law and her best friend each commented, “GORGEOUS.” People compared me to the Kardashians, Adele, and J. Lo. A stranger reposted my photo, declaring that a teenage character I’d once played was “all grown uppppp!” One friend commented three times and texted me “obsessed.” Another texted me, “Sarah That Photo Is Incredible It’s So f*cking pretty,” before asking where my dress was from. When I texted back that I was wearing fake boobs, and wouldn’t otherwise be comfortable wearing that dress, she didn’t respond. Someone messaged me, “giving me literal divine feminine.”

As I soaked up the support, I felt conflicted. Was I catfishing everyone? Did they think those were my real boobs? Would they have reacted as enthusiastically if I hadn’t used Facetune? Why did only two people I know comment “what is happening” and “wow what is going on”? Wasn’t I “all grown uppppp!” before this? Most hauntingly, I wondered, Oh god, is this how they want me to look?

I couldn’t wait to clarify that this photo wasn’t of Hollywood Actress Sarah Ramos. It was a b*tch named Successica.

Step 4: Successica’s Endless Success

When I first started using Instagram 10 years ago, I named my account after Arrested Development’s Ann Veal, a character defined by her forgettableness. I used it to post pictures of Whole Foods milk dispensers with handwritten signs stickered onto them that warned, “Careful! Comes out like a rocket!” The first selfie I ever shared was ironic. Even though I was an actor, using a social media account to post flattering selfies felt icky, indulgent, cringe. I’d grown up inhaling glossy magazine stories about gorgeous famous women being unwittingly “discovered” in shopping malls and breezily carted off to their destined stardom. I had the same ideas about fame that I did about beauty: that it just stuck effortlessly to the people who inherently deserved it. I didn’t realize that that was exactly what PR people were paid to convince me to think.

When the Kardashians stormed the media scene, I enjoyed how obviously their success was due to shameless fame-chasing and relentless self-promotion. It forced us to culturally acknowledge that fame and influence must be actively cultivated. Kim doesn’t just get paparazzi’d — she stages her own photo shoots meant to look like she’s being paparazzi’d. It’s impossible to look at the Kardashians and not see a heavily produced image. Or at least it used to be before social media enabled everyone to follow Kim’s playbook. Now everyone can keep up with us on our own Instagram reality shows. We can airbrush our own photo shoots. We’re our own PR people now.

I wanted Successica’s photos to sell Kim’s multi-hyphenate fantasy, but halfway through the shoot, I was dehydrated because taking off my leggings and butt pads to pee without popping off a glue-on nail was more annoying than not drinking water. Underneath the breastplate, my skin was slick with sweat. I couldn’t get in and out of my clothes on my own, and my back was stiff from sitting in hair and makeup for so long. When I asked how the Kardashian-Jenners could do this all the time, Eddie told me that if this were a real Kardashian shoot, we’d all be making bank.

But then I remembered listening to a podcast in which Emily Ratajkowski offhandedly mentioned that models often don’t get paid to pose in fancy magazines because the exposure is considered compensation. If elite publications had paid Ratajkowski in exposure, it didn’t seem safe to assume any of the women whose images I consumed were making actual money.

I certainly wasn’t. After months of posting videos on Instagram that garnered exposure — millions of views, press, engagement with A-list celebs — the app’s beta advertising program had only paid me $300, which barely covered the cost of a ring light. Come to think of it, hadn’t I spent 20 years hoping that letting executives watch videos of me auditioning for free would lead to a movie-star career? Even Miz Cracker admitted she spent more money to compete on Drag Race than she had on college.

I’d thought that exposure came with riches and opportunity, not in lieu of it. But maybe there was a reason that the people (men) who profited off images of women intentionally stayed off-camera. The man who founded social media to rate women as hot or not wants so badly to protect his own image that he slathered his face in sunscreen to confuse the paparazzi. Recently, a friend told me she saw the super-rich creator of Facetune on a dating app. His photo was unedited and makeup-free.

Step 5: Billboard Mania

Every time I drive through the intersection of La Cienega and Santa Monica Boulevards, a semi-truck-sized sexy photo of Kylie Jenner looms over me. Sometimes the billboard is advertising Kylie Cosmetics, sometimes Kylie Skin. Sometimes it’s just wishing Travis Scott a happy birthday. Well, Kylie may have one seductive billboard advertising a company named after her, but Successica has two. And she posed in a bikini on top of a car in front of them, because sex sells.

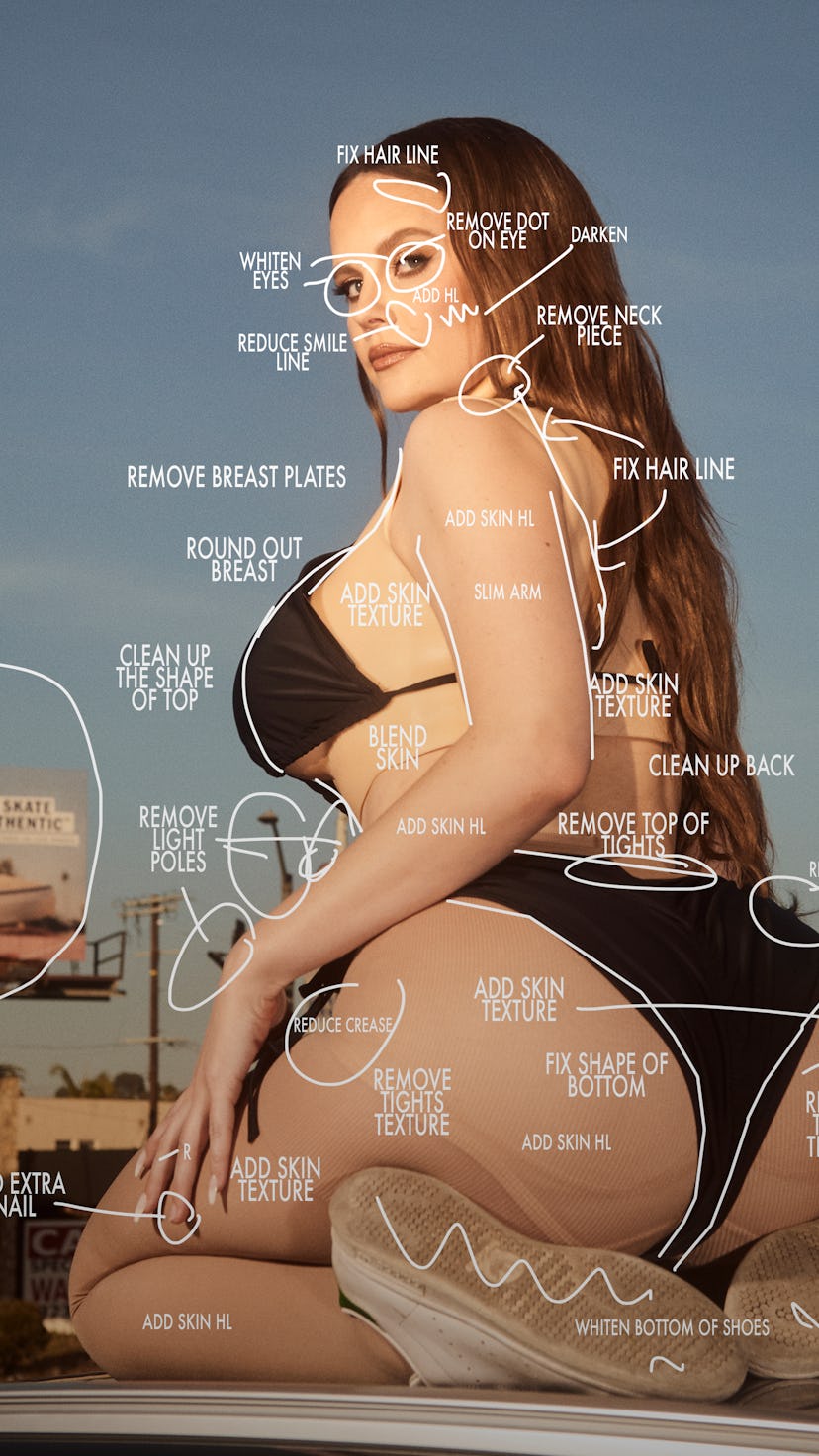

In the retouched version of this image, I look so exposed. But in reality, my legs and ass are completely covered. The only swathes of actual skin showing are my arms, mid-back, and face. You can’t see the dude with a face tattoo who stopped on the sidewalk to stare or the work Kelsey did to make my leggings look “skin texture.” To convey just how many drastic and subtle changes were made, I’m including the original, marked up with retouching notes.

At the end of the sexy photo shoot, I paused to look at a friend’s Instagram story. She’d posted a quote from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, and the screenshot I took of it is the last photo on my camera roll from that night: “My painting is what I have to give back to the world for what the world gives to me.” She had natural landscapes. I have Influencer Drag.

Hair: Eddie Cook

Stylist: Amanda Massi

Photographer: Kelsey Hale

Makeup: Auður Jónsdóttir

Photography Assistants: Belva Chan, Tutu Lee