Books

Religious Romances Come Out Of The Confessional

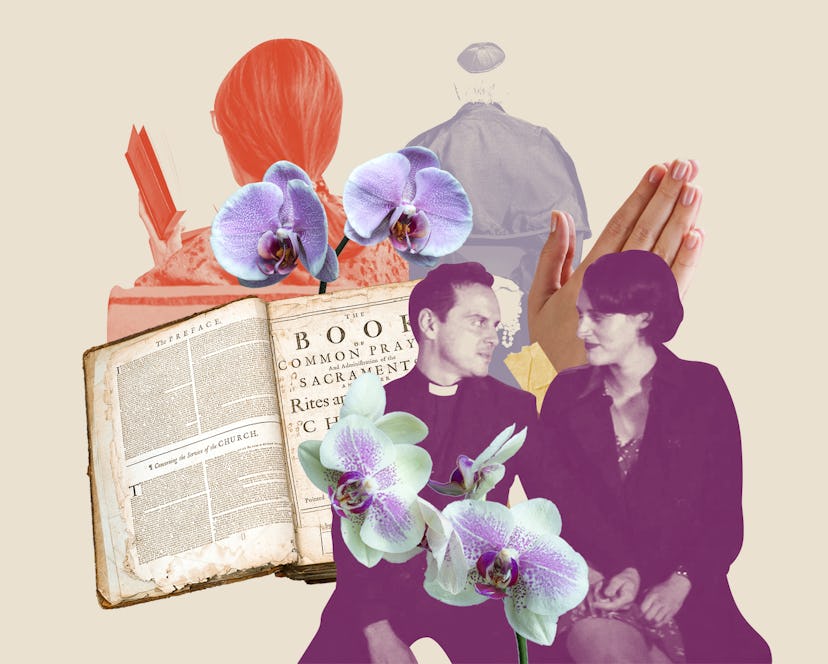

Fleabag’s Hot Priest isn’t the only one mixing love and worship — the romance novel industry is experiencing something of a religious renaissance.

Nearly every line in Fleabag is quotable, but one in particular has proved unforgettable: the Hot Priest’s command to “kneel.” Fresh out of the confessional, the Priest, played by Andrew Scott, issues his edict, and he and Fleabag (Phoebe Waller-Bridge) finally act on their long-simmering attraction.

Fleabag’s critically acclaimed (and quite unholy) second season is far from the only contemporary work mixing religion and romance. Now more than ever, romance publishers are snatching up novels about characters with deeply held religious beliefs.

One of these buzzy releases is Andie J. Christopher’s Hot Under His Collar, which veers into territory that some romance readers, especially more religious ones, might see as sacrilege: Christopher’s protagonist is a priest named Father Patrick Dooley who is, to put it simply, Not Like Other Priests. He’s cool, he’s critical of the Church, and like many millennials, he hates the bureaucratic runaround he gets from his bosses. But that doesn’t make it easier when he falls for a woman who is very much not grounded in faith.

Christopher’s novel is only the start. There are more romances than ever that unpack religion generally — Alisha Rai’s First Comes Like, and Uzma Jalaluddin’s Ayesha at Last, and Hana Khan Carries On, for example, all feature Muslim leads grappling with their identities as they find love — but so far, it seems that only Judeo-Christian novels will go as far as to feature characters seducing religious leaders.

Sierra Simone, the author of the aptly titled romance novel Priest, thinks conversations around identity and diversity are to thank for the sub-genre’s expansion. Questions about the lack of protagonists with non-Christian religious affiliations and religious leaders as potential love interests are have made their rounds in the romance community for years, and publishers are finally starting to take notice. “Religion can be influential on a person’s identity, and so it’s important to showcase it in romances for more inclusive representation,” adds Kristine Swartz, a Senior Editor at the Penguin imprint Berkley who acquired Christopher’s book. “We want readers to see all parts of themselves in the characters they read about.”

Prior to this religious renaissance in mainstream romance publishing, a niche market for explicitly Christian, values-driven love stories (known as “Inspirational” romances) has existed for decades. But books like Hot Under His Collar are a very different beast, written with a very different audience in mind — and Christopher doesn’t think it’s a coincidence that as these romances proliferate, religious affiliation in America falls.

Christopher notes that millennial and Gen Z readers, who constitute a large portion of the romance genre’s audience, are two of the least-religious generations. “I think the fact that people are questioning their own faith and their own spirituality leaves room to talk about, ‘What does religion mean? What does it do in our lives?’” she says. Romances often mirror the big questions that readers are grappling with, from stories in the 1970s that dealt with marital rape — which some consider a response to the threat of sexual assault in women’s lives — to the rise of #MeToo-aware romances of the past two to three years. It follows that religion, another hot-button issue, would make its way into the genre.

Simone argues that in addition to a steamy romance, Priest explores the sensual nature of Catholic rituals, which can feel at odds with the faith’s strict, abstinence-heavy moral code. “There's a lot of cognitive dissonance in being a Catholic, because it's so deeply sensual in a sensory [way],” she explains, citing her own childhood experiences in church (she’s since stopped attending services). “You're asked to kneel while incense curls around you. You're asked to pray in rays of light that are stained with stained glass. You're asked to come up and taste the flesh of God.” Sensuality and worship do often go together. In religious ecstasy — an experience famously captured by Bernini in The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa — this overlap reaches its apotheosis.

Another selling point for religious romances, Simone notes, is the element of escapism. “Most of us are not falling in love with rabbis and priests,” she says. “We're a lot more likely to fall in love with, I don't know, an insurance adjuster.”

Rosie Danan, whose book The Intimacy Experiment (also acquired by Swartz at Berkley) features a romance with an attractive young rabbi named Ethan, says she decided to make her love interest a religious leader because her protagonist Naomi needed “someone [who] can meet her on her level and really engage her.” Of course, getting entangled with a priest or rabbi also poses challenges, which she worked through with her Jewish family and friends. “There were some specific conversations that I had around, ‘Okay, what are the attitudes that specifically a rabbi would hold around sex? What feels realistic?” Danan says. She settled on making Ethan a rabbi of the Reform denomination, who wouldn’t have to abide by rules about abstaining from sex entirely or before marriage, which gave her more narrative leeway.

Romance is a genre rooted in fantasy, and fantasizing about such a meaningful part of life has its drawbacks. While some atheist or agnostic readers may see these romances as tools for interrogating their faith (or lack thereof), more devout readers may not be able to look past the often sacrilegious implications.

Caroline, a romance reader and Methodist who studied religion in college, feels that authors have a responsibility to contextualize their stories with the issues that religious communities are facing, the #ChurchToo movement within the Evangelical community being one of them. “It's important to understand the context in which [these books are] written and the experiences that certain people have had,” she explains. “And I can see how some folks who may have experienced sexual abuse or other kinds of trauma within the Church might find these books very difficult to even acknowledge, and might find it difficult to understand how some people could be entertained by a relationship like that.”

Morgan, a fan of romances and a practicing Catholic, doesn’t read love stories that center her faith because they hit too close to home. “Anytime there's a priest, even in a movie, it’s [a question of], how does that priest compare to priests that I've interacted with?” It’s easy to understand why some people might not want to read a lusty novel that reminds them of the guy who regularly hands them communion wafers. Some of the intrigue is lost.

Not for everyone, maybe, but certainly for some. Sacrilege aside, romance and religion do seem to fit together. As Simone says, readers crave “a love that makes you make hard decisions, a love that forces you to clarify who you are and what you're supposed to be doing on this planet Earth.” Who better for that than a priest?

This article was originally published on