28

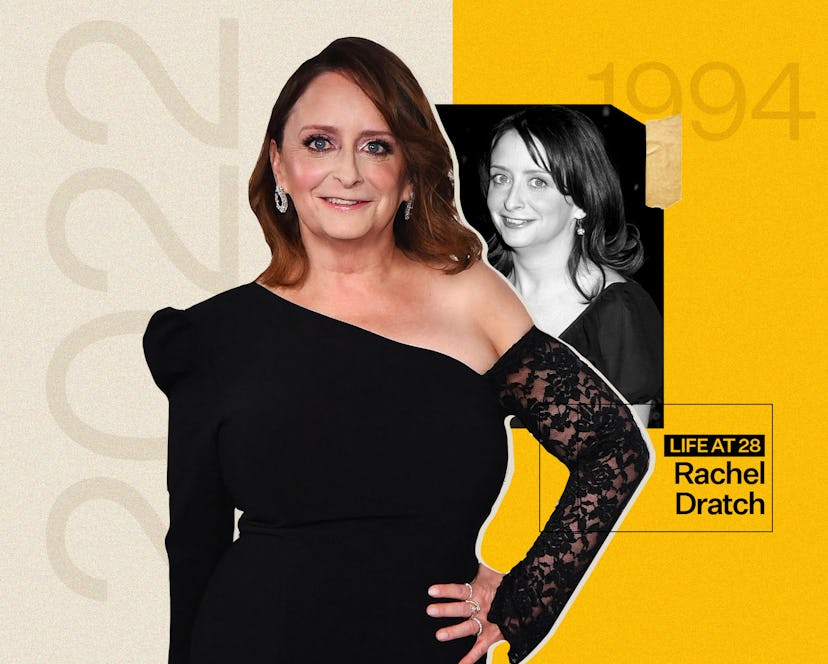

At 28, Rachel Dratch Was Mingling With Steve Carell & Inhaling Secondhand Smoke

As part of the storied Second City improv troupe in Chicago, Dratch got a crash course in comedy from the likes of the future Office star.

To a 28-year-old Rachel Dratch, improv was everything. The Chicago improv scene was her teacher, muse, and place of worship. “You know the whole 10,000 hours thing? I really believe the more improv you do, the better and better you get,” the former Saturday Night Live star tells Bustle, referencing Malcolm Gladwell’s timeline for mastering a skill. “People are like, ‘How can you learn improv? You're making it all up on the spot.’ But you just get more comfortable being in front of audiences, stepping out, and not knowing what you're going to say. That’s sort of how I imagine being 28 — [practicing] improvising.”

Five years after moving to Chicago with her sights set on the storied Second City improv troupe in Chicago, 28-year-old Dratch was working tirelessly on perfecting her skills. “Everyone had come from all over the country because that was like the Mecca for comedy,” says Dratch, now 56. The program known for producing a murderers row of talent already had formidable stars during Dratch’s tenure, including Stephen Colbert, Amy Sedaris, Steve Carell, and Nia Vardalos, and Dratch initially struggled to make her mark. “Your very first classes are kind of scary for anybody,” she recalls. “Even when I improvise now, and I haven't done it in a long time, there's a fear around improvising.”

So she put in the work — and the time — and stayed at Second City for ten years, honing her craft before joining SNL in 1999. There, she quickly became known in her seven-year run for her wry, sardonic characters, from Boston teenager Denise and Hollywood producer Abe Scheinwald to Debbie Downer, a pessimistic weirdo who’s now so ubiquitous in culture that her name has become a catch-all for people who give off bad vibes. Dratch believes that these characters wouldn’t have been possible without her time at Second City, putting in those 10,000 hours. “Everyone has their own thing,” says Dratch, who’s now starring in POTUS on Broadway. “You pick up on everyone’s talents and you can’t fake it. You can just be like, ‘What's my vibe? What's my style?’ Then it all seeps in and somehow you get better.”

Below, Dratch talks about secondhand smoke in the bar scene, meeting Lorne Michaels, and getting over her fear of failure.

Take me back to 1994, when you were 28.

I was living in Chicago and I was in the Second City touring company. The way the touring company worked is you lived in Chicago and then you'd go off for a weekend here and there. Back then you got paid $65 per show, but the cost of living was so low you could actually live off of that. I was just around a lot of really talented people and we lived for improv. It was this community where everyone kind of rose up together. It was my artistic life and social life all rolled into one.

What did a typical Friday night out look like for you?

If I had a show or something, everyone would go out afterwards from their various shows. There were two bars right near Second City. There was a bar called The Last Act across the street. It was totally filled with smokers, you'd come home and the next day you would smell of smoke in your clothes and your hair. I'm sure it was highly unhealthy. That bar closed at two. Then there was another bar on the other side of the street called The Old Town Ale House and that one was open until four. Then this one lady everyone called Yoyo would be like, "Last call!" Then we'd even go to a diner after that. It was really late nights.

Were you developing any characters at the time?

Jon Glaser and I wrote this scene together where I played this child star who was now grown up and still acting like a child star. I would sing about puppies and rainbows and stuff like that, even though I was trying to get a job in a real office.

Was Saturday Night Live your dream in those days?

A lot of people that live in Chicago are like, "Maybe SNL," because SNL would scout at Second City. Then you see, "Oh wait, there's a hundred people. We're not all getting on SNL." You kind of let it go because when you’re in the touring company, you just want to get on one of those stages [at Second City]. When I first got on the main stage, I was 29. SNL came and they flew out so many people [to audition], but I wasn’t picked. I was like, "I'm not going to ever make it on that. Maybe I'm not good enough to do this." All that stuff that can go through your head. I had a disappointed walk around the park with a friend, but then you let that go because you’re trying to come up with stuff for your next show.

Then, eventually, I had been on the main stage for almost four years and SNL came back to scout. By then I had a lot more experience and I had all these characters. So that's when I got seen.

Has there been a moment in your career where you felt like you made it?

Getting SNL. I didn't get it the first year I auditioned. The first year I felt really good about the audition because I didn't get out of there like, "I should have done this. If only I'd done that." Then the next year I felt kind of okay with the audition. Then they said, "Okay, we'll tell you by a certain date," and then the date came and went and they didn't tell me. I thought it wasn’t going to happen. But then I got a call two weeks later, “Lorne [Michaels] wants to meet with you.” So you go meet with Lorne and it's just kind of a quick meeting. You're chit-chatting. Then they told me, "We'll let you know within a week."

I was walking around with my rudimentary cell phone and at the very end of the day I get this call and it’s Lorne and he’s like, “They'll call you to set up the deal." I was like, "Does this mean I have the job?" And he's like, "Yes." Then I called my parents. It's just this crazy dream call.

Looking back, do you have any regrets?

When you're starting out, if you have a “failure,” I would take that and be like, "Okay, I'm not good at this." But the graph [of life] isn't a straight line. It's a zigzaggy kind of line. The graph might dip, but it'll go back up again.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on