Bustle Book Club

Patrick Radden Keefe’s Hollywood Homecoming

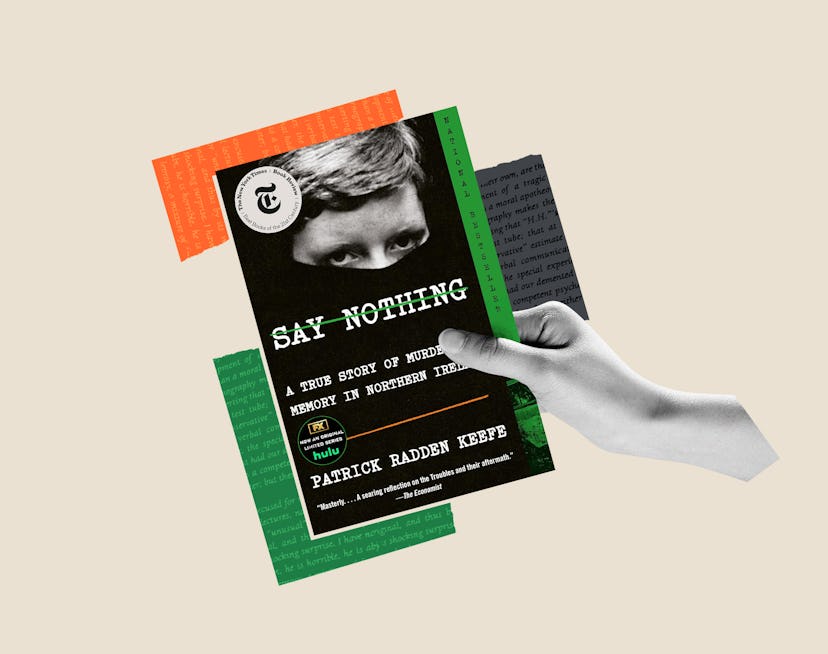

The Say Nothing author had abandoned his screenwriting dreams — until producers expressed interest in adapting his books.

Before Patrick Radden Keefe began his tenure as a New Yorker staff writer, he spent years trying to hack it as a screenwriter. “I wrote a movie for [famed producer] Jerry Bruckheimer. I wrote a pilot for HBO about the role of guns in American life. I adapted a Jo Nesbo novel for Warner Bros.,” Keefe says.

While none of these projects ever made it to the big screen, the experience proved invaluable. “The structure of a screenplay really did influence my writing. Like, ‘When do you get into a scene and when do you get out of it? How do you intercut between different stories?’” the journalist, who has reported on everyone from Anthony Bourdain to El Chapo, tells Bustle. “Those kinds of things were really helpful for me in thinking about how to structure a nonfiction story.”

In addition to the highly cinematic, exhaustively reported features Keefe writes for the New Yorker, he’s also managed to publish a variety of bestselling nonfiction books. And last week, the TV adaptation of Say Nothing, Keefe’s opus set during the The Troubles in Northern Ireland, debuted on FX to rapturous reviews. The series, which follows the young radicals at the heart of the Irish Republican Army, is at once a deeply researched historical portrait and a timeless story about oppressed people lead to political violence — a narrative that feels particularly relevant to the ongoing war in Gaza.

Keefe didn’t write the series himself — he imposes a “church and state divide” with his adaptations — but he was still heavily involved in the process, speaking frequently with lead writer Josh Zetumer. “A drama is not a documentary. A drama is not a nonfiction book. The rules are different. I am entirely fine with the notion of having to invent dialogue or having to create scenes to compress the story,” Keefe says. “But it was a constant conversation among the producers, writers [and I] of ‘Does this seem like a permissible extrapolation from the book?’”

As Keefe’s books go Hollywood — an earlier work of his, Snakehead, is now in the works at A24 — he’s finding his interest piqued by screenwriting once more. He has an original script he’s working on with some of Say Nothing’s producers now, the premise of which has nothing to do with any of his prior works. But for Keefe, it’s all of a piece. “When my agents were pitching me for screenwriting jobs, they’d say that I was the journalist, too,” he says. “It took me years to realize that actually there was more influence going in the opposite direction — that the economy of a screenplay was really helpful for me in thinking about how to structure a nonfiction story.”

Below Keefe reflects on sweat equity, Hollywood memoirs, and toggling between projects.

On the Old Hollywood books that inspire him:

I grew up on Peter Biskind’s books. The best of them is about Hollywood in the ’70s, and it’s called Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. I also loved Hello, He Lied by Lynda Obst, The Man Who Heard Voices about M. Night Shyamalan, and Mark Harris’ book on Mike Nichols.

On his “stop-start” work approach:

I always have multiple projects, which I find really helpful because so much of the investigative work that I do is stop-start. I once heard my colleague Lawrence Wright refer to this as “crop rotation,” which I think is a great way of thinking about it. Basically, when I get very frustrated with one project, it’s really helpful to have another project that I can turn to. Then, usually by the time I get frustrated on that other one, something might’ve shaken loose on the first and I can turn back to it.

On killing his darlings:

I can spend eight or nine months working on a piece, and there could be somebody I interview for two hours, and what they get is a line. ... There’s a danger in thinking that just because you did the research, it belongs in whatever you’re writing. The sense that your own “sweat equity” is some basis for including something. In Hollywood they would say “kill your darlings,” but you just need to be ruthless about what merits inclusion.

On his go-to revision technique:

If I write a paragraph, I will then read the paragraph aloud to myself. I’ve found that it’s like an X-ray that can pick up the infirmities in whatever you’ve just composed.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.