Books

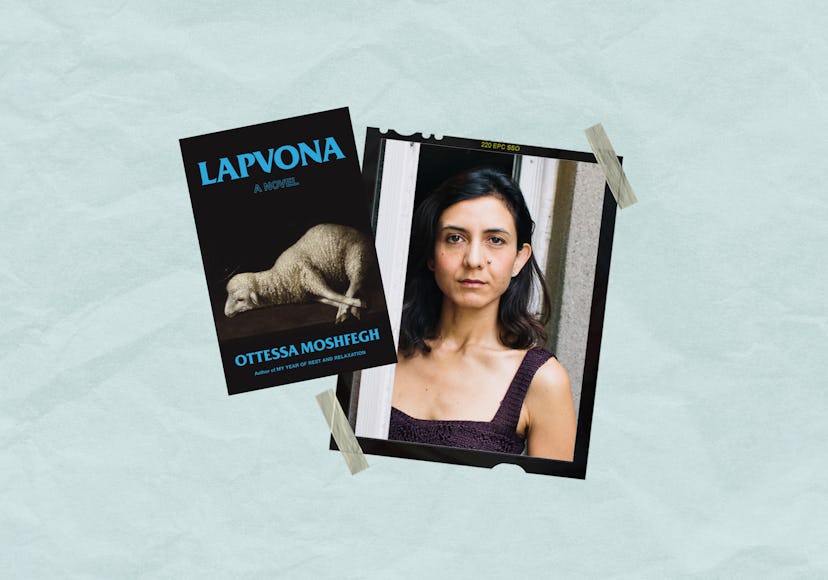

Ottessa Moshfegh Is Happy To Be Your “It” Girl

Despite steering clear of Instagram and Twitter, the author has amassed a wealth of cultural currency.

When I pull up to Ottessa Moshfegh’s driveway, the first thing I see is the bumper sticker on the car in front of me: “Honk if you don’t exist.” I resist the urge to lay on the horn.

The author herself is standing on the terrace, dressed all in white and finishing a cigarette. Her East Pasadena home, a historic Pueblo-style property enveloped by palms and pines, serves as an attractive backdrop. It would be catnip for influencers — the same ones who have taken to conspicuously carrying Moshfegh’s novels in one hand and a pastel Telfar bag in the other. Not that she minds. “I love books as objects,” Moshfegh tells me over another cigarette. “I love books as experiences as well.”

Moshfegh has made a name for herself writing fiction about “unlikeable or even repulsive” people, and been hailed as “a pioneer of a new genre of slacker fiction” and “the most interesting contemporary American writer on the subject of being alive when being alive feels terrible.” Her 2018 novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which chronicles a beautiful yet disaffected Upper East Sider who spends a year trying to snooze away her emotional baggage, became a sleeper hit — readers living in a sociopolitical hellscape, it seems, understand the impulse to nap through life — and solidified Moshfegh’s reputation as a literary “it” girl. Suddenly, she was everywhere: on a Vogue Italia cover, in a print ad for Proenza Schouler, walking the runway at New York Fashion Week. People no longer just want to pose with her books; they want to align themselves with Moshfegh herself. (They’re out of luck, though, if they try to tag her: She doesn’t have a presence online, aside from a Depop store where she sells secondhand clothes; once her fans learned about it, the shop’s handful of followers ballooned into over a thousand.)

In person, Moshfegh plays down the Rest and Relaxation hype. “It’s a good book,” she says. “But I don’t think it’s the best book I’ll ever write.” In fact, she’s much more excited by the medieval-set Lapvona, her fifth novel, out now via Penguin Press. She began writing the story about an oppressed fiefdom during lockdown with the goal of exploring multiple characters’ perspectives for the first time, rather than limiting herself to one “judgmental, anti-social” antihero. “I had personally been resisting thinking of myself as being part of society, and I think there was something that broke during the pandemic. The bubble that I thought I was living in smashed,” she says. “I wanted to write about the world, partly because I missed it and was reflecting on it, and it was so interesting all of a sudden.” In other words, she woke up from her nap.

Below, Moshfegh discusses her literary stardom, her ventures in the fashion industry, and the wildest thing she did during the pandemic.

In a 2016 interview with The Guardian, you said that you wrote Eileen as a way to achieve commercial success. Looking back, how do you feel about the decision to write something with the goal of achieving fame?

I think what people may not understand if they’re not writers is that you can spend your whole life struggling in the dark writing short stories, and nobody will give a sh*t. You will have to have another career. No one can build a career writing short stories, except for maybe … I don’t know, Edgar Allan Poe? But I’m not Edgar Allan Poe. Maybe what didn’t come across in that Guardian interview is that I didn’t have anything to do with mainstream taste ... My career was nothing. I had had jobs in New York in publishing, and then worked as an assistant for an oral historian. I would’ve ended up working in an office, and I really wanted to try to make a living as a writer.

I got $100,000 for Eileen, and that was mind-boggling at the time. But now let’s break it down: I had to pay my agent. I had to pay taxes. I had to pay rent. It’s not like I walked away and said, “I’m rich!” I had been living off almost nothing, so it barely took me above the poverty line. Well, I shouldn’t say “poverty line.” I’m very lucky to have had a safety net, like my parents who would’ve let me live with them. And I had an education … I mean, Christ, I have a master’s degree, and I could not find a job [in LA]. I think that was my fault. [Laughs.] I did not know how to operate in Los Angeles.

You’ve been exploring opportunities outside of the literary world for some time, like when you walked for Maryam Nassir Zadeh at New York Fashion Week earlier this year. How did you feel about being asked?

Flattered, scared, and grateful for the opportunity. I am someone who has not had a well-tuned opinion of my exterior. I felt that contributing and participating in that way at a public event that was about a presentation of what things look like, and what it means to look that way, would be healing. I grew up with so much dysfunction in terms of my body image and food issues, and self-loathing. I just thought it was like the universe telling me, “Okay, get over it.”

Also, do you mind if I smoke?

No, please go ahead. When you’re asked to work with people in fashion and other similar industries, how do you feel about them leveraging your cultural capital?

I was offering it. Proenza Schouler asked me to be in a campaign — it was just, like, one photo — a couple years ago, and through that experience I met this woman who is now my agent for fashion-related bookings. And last year my friend Jordan Wolfson, who’s an artist here in Los Angeles, asked Emma Cline and I to be in a photograph for a special issue of Vogue Italia with multiple covers. And while I was doing it, I thought, “This is actually really interesting to be part of a creative process as a physical being.”

I’ve always been a fashion nerd. When I’m procrastinating, I’m usually watching disgusting YouTube videos about whatever garbage… Actually, I started watching a lot of footage of police interrogations. Just the raw footage is fascinating, seeing these people who are inevitably guilty lying for hours, and then finally getting so confused by their own lies … it’s just the way the detectives use all these techniques for getting people to tell the truth. But if I’m not doing that, then I’m watching old runway shows.

Were you one of those kids who was runway-walking up and down the hallways of your childhood home?

No. I was always short. I’ve been this height since I was 11. So I knew I wasn’t going to be a model … my runway walk is nothing. It was just me walking. In fact, when I got on the runway at Mariam’s show, I completely freaked out and forgot how to walk. I thought I was going to fall over in my shoes. And then I went the wrong way. I was very stressed.

Have you heard or read about the phenomenon of “book styling”? Apparently, celebrities are hiring book stylists to give them books to carry in public, or to curate the books in their homes. Essentially, it’s about the aesthetic value of literature as objects.

I mean, okay. Whatever floats your boat.

It’s like a branding thing. Do you think of yourself as having a brand?

Yes, because that comes up in conversations with the people who I work with. I would never worry that something that was my idea would be “off-brand,” because that’s impossible. But there are things that are not in line with my values that are sh*tty, that I wouldn’t want to associate with. So I stay away from certain things.

Like what?

Like, I wouldn’t want to write on a TV show that I didn’t like, you know? I tend to just take the assignments that excite me, or that feel like interesting opportunities that the universe is delivering. I’m really happy with what I get to do. I’m writing films, novels, and short stories … and some journalism too. Right now, I’m working on a profile for GQ, and that’s been such a fun assignment. The stuff that I’m doing in fashion is really interesting and fun. I really don’t mind thinking about the usefulness of writing in a commercial way — if it’s interesting to me.

You don’t have an Instagram or Twitter, but years ago I went to one of your readings and you said that you do lurk these sites through an anonymous account. Do you still lurk?

It comes in waves, where I’ll put my name into Twitter to see what people are saying on a random day. And usually, it’s a lot of things in other languages, and then there is usually one or two people who have their name in their Twitter name, so I just end up scrolling through their tweets. There’s never anything really good, so I kind of don’t care. I think it’s a little self-destructive to do that, so I try not to.

What’s the worst thing you’ve read about yourself while lurking?

I don’t know. I can’t think of anything. I think the thing that would hurt my feelings the most is someone calling me ugly.

Yeah, that’s personal. It’s not even about your work at that point.

Yeah. I’m sure there have been times where I’ve been like “bleh,” because I was raised to revert to insane arrogance whenever I feel threatened. Like when someone says something sh*tty about me, I generally just hate them in response. And then I forget about it. Like, “She’s a f*cking moron.” And then walk about grumbling or whatever, and then I forget.

What would you say is the most unhinged thing you did during lockdown?

Oh my God. I was walking my dog Walter on a back road near my house, and a neighbor who I’ve never seen before came out of his house. He had headphones and a mask on, and was coming out of this gate that I didn’t even know was there. And I just happened to be passing by, and there was this very awkward negotiation of space, and I wasn’t wearing a mask. This was before we knew how COVID worked, so he was probably really scared, and he went on this tangent about how I was putting the entire neighborhood in danger and started shaking his finger at me. And I apologized, but he went off on me one more time, and it was like a switch flipped. In my head, I was like, “I’m about to go totally insane.” And I fell down on my knees, and I prayed to God for him to forgive me for, you know, “disrespecting” my neighbor. And my prayers were so intense, and I was praying out loud, that I moved myself and I started crying.

Wow.

I was still angry at him for shaking his stupid f*cking finger at me. Anyway, he said, “If you’re really a spiritual person, you would’ve been wearing a mask.” And that’s when I kind of flipped. Obviously we were both being crazy, but I really lost it, and didn’t get up off my knees until he was far, far away, and kept looking back. And I’m sure he thought I was really mentally ill … But that was probably the most unhinged moment for me.

That reminds me a lot about Lapvona, especially the epigraph, which is from a Demi Lovato song: “I feel stupid when I pray.” Is there any connection between your unhinged neighbor and that quote?

I’m a God thinker. I think about God all the time, so it wasn’t a freak accident. I encountered that Demi Lovato song — “Anyone” — on YouTube, years after she performed it at the Grammys [in 2020], which was not long after her overdose. So she starts to sing, and she’s crying and has to start over, which is a really hard thing to do. I thought it was a really intense performance about crying out to God, for anyone to come help her. And I couldn’t let go of that line, “I feel stupid when I pray,” because it felt so honest, and then I realized it could be interpreted in so many ways. Like, do I feel stupid when I pray because I am stupid, and this is my true stupidity? Or do I feel stupid when I pray because praying is pointless, and it’s a stupid thing to do?

This interview has been edited and condensed.