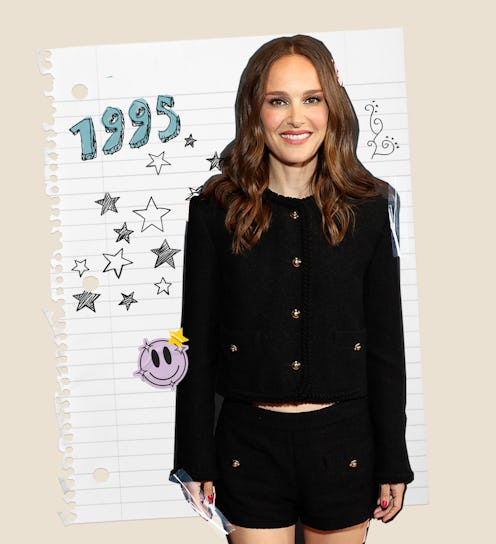

14

At 14, Natalie Portman Was Starting To Deal With “Extremely Inappropriate” Press

As co-founder of the Angel City FC soccer team, she’s in the business of championing female role models.

When Natalie Portman turned 14 in the summer of 1995, the decade of grunge fashion and uncensored TV was well underway. MTV had lightened its playlist of music videos to make room for unscripted shows like The Real World. John Grisham’s crime-and-punishment novels reigned atop bestseller lists.

In that cultural context, Portman started filming the machismo crime epic Heat, in which the two alpha males sacrifice domestic stability for their opposing obsessions: committing large-scale crimes, for Robert De Niro’s ex-con; or squashing them, for Al Pacino’s police detective. Portman played the latter’s stepdaughter, a troubled teen who serves as a type of humanizing force for Pacino’s character.

It was one of her first film roles, and she held her own amid a marquee cast, folks like Val Kilmer, Amy Brenneman, Ashley Judd, Danny Trejo, and Diane Venora, who played her mother.

Roughly three years before, at age 11, she’d been stopped at a Long Island pizza parlor by a talent scout for Revlon. She declined a modeling offer but parlayed the conversation into landing an acting agent. “I was largely very lucky,” says Portman, now 41, of being famous so young. “People treated me very normally, but it did definitely affect certain things in high school.”

At 13, she’d transferred to a large Long Island public high school, where she excelled academically and considered herself part of the “JAP-y group,” according to a Rolling Stone interview from a few years later. She would work primarily over the summer months, and by the time she headed to Harvard after graduation, she’d already landed a three-film contract in the Star Wars prequels as Queen Amidala.

“I remember a local radio station publishing when my graduation was, for people to come show up and find me, or people auctioning off my yearbook — things like that,” she says. “It [all] coincided with the early days of the internet too, so it was a wild time.”

Recently she’s been thinking back to the ’90s, particularly to the summer of 1999 when the U.S.A. women’s soccer team won its second World Cup. “We knew them by name in a way that it was part of the larger culture,” Portman says of the 99ers, as they’re often called. Their win, from Brandi Chastain’s penalty kick, was viewed by a record-breaking 40 million Americans, and the 99ers introduced a new type of female role model into the popular consciousness. Many of those players, including Mia Hamm and Julie Foudy, are investors in Angel City FC, an expansion soccer team that Portman co-founded in 2020.

The Los Angeles club, now playing its second season, is the subject of the new three-part HBO Max documentary, Angel City, which Portman executive produced. It’s a great sports film, following the team’s creation and inaugural year, perfect for both National Women’s Soccer League diehards and Ted Lasso fans mourning the series finale.

Below, Portman reflects on the pitfalls of teenage stardom and the part that got away.

Congrats on the documentary. Since we’re looking back on your teenage years, I thought we could start with the 1999 Women’s World Cup, even though you were a bit older than 14. What do you remember about that championship game between the U.S. and China?

I think it was my first time seeing women playing team sports [for] a mass audience, where even people who are not really into sports, like myself, knew who Mia Hamm, Julie Foudy, Chastain, and all of these players [were].

What was it like when you then met them as part of Angel City, especially since many of them are partial owners of the team?

It was so exciting and inspiring to get to meet them, and to be part of this together.

So you turned 14 in 1995, which is when you filmed Heat. Do you have any favorite memories from that set?

Al Pacino had rehearsals at his home with me and Diane Venora, and that was just such an extraordinary experience, to get to work together. He was so kind and generous.

How did you balance being a working actor and also a good student?

My parents didn’t really let me miss school, so it would always be around a school vacation. Then sometimes I would miss a few days or something, but then I would have an on-set tutor to help me keep up with my schoolwork.

When did you schedule the auditions?

We lived in the suburbs, and my mom would drive me into Manhattan a few times a week to have my meetings or auditions. Often I’d finish school, and she’d pick me up, and we’d go straight to the city.

Did you have any dream roles from that time period that you had your heart set on that you didn't get?

Oh, I was dying to be in Les Misérables [on Broadway]. They were auditioning young Cosette, and there were kids I knew from dance school who got the part. That was always a dream for me at that age.

When you didn’t get a part, how did you handle that disappointment?

[I’d] just move on and not dwell on it, to always treat it as the way it was meant to be, that it was meant to be somebody else and I’m meant to do something else.

Sounds like a healthy approach. One of the things that we inevitably end up talking about in this column is puberty. What was your experience of puberty, since you were already in the public eye?

I mean, it was definitely intense to be in the public eye for that part of life, because I’d have people mentioning changes in my body [in] articles they’d write about the movies I was doing. I don’t think I understood at the time how wrong it is to feel like any person has the license to comment on anyone else’s body, but particularly not an adult commenting on a developing child’s body. [It’s] extremely inappropriate, to say the least.

When do you think you started realizing that it was wrong?

It took me being an adult, I think even a mother, to realize how wrong that was.

When you read a review and felt some way about it, who did you talk to?

I kind of kept it to myself. I don’t know that I talked about that a lot. If I did ever come across it, to try not to take it to heart. But I learned quickly not to read it.

I was just listening to your 2020 interview on Dax Shepard’s podcast, where you talked about how you cultivated an image of being serious and prudish as a teenager, as a type of safety mechanism. Did that apply to both your public and private lives, or were you able to separate them?

I’m sure there’s some crossover between public and private, but in my private life I was able to be more silly and let my guard down.

And last question: What advice would you give to your 14-year-old self today?

To not take everything too seriously and just be silly.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.