Books

“When Was The Last Time You Played A Death Game?”

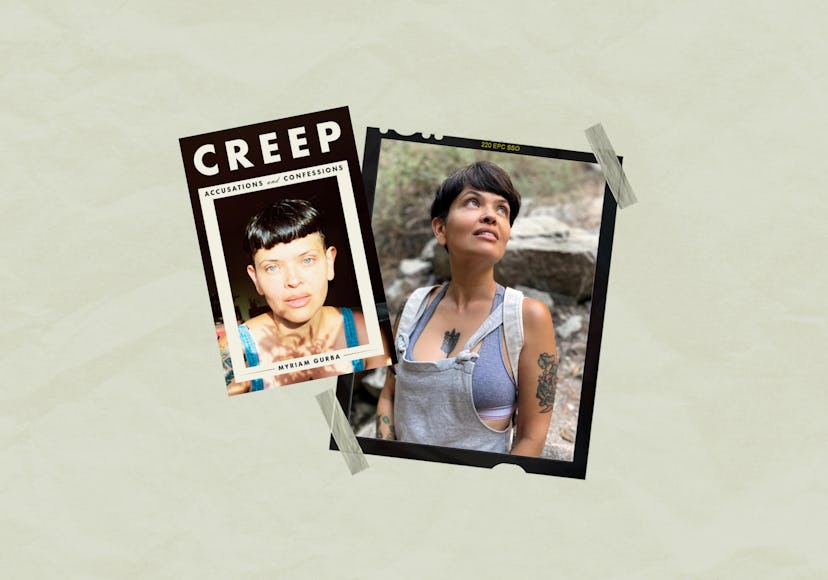

In an excerpt from her new memoir, Creep, Myriam Gurba ruminates on why her childhood playdates often took a morbid turn.

In Myriam Gurba’s new book, Creep: Accusations and Confessions, the writer interweaves personal anecdotes with searing cultural criticism. Below, read an excerpt from the memoir’s first pages, in which Gurba reflects on her childhood fascination with macabre games — some of which were played with Barbies.

It’s easy to get sucked into playing morbid games. When I was little, I happily went along with a few.

I played one with Renee Jr., the daughter of the woman who gave me my second perm. She and Renee Sr. lived in a tall apartment building across the street from the used bookstore where I some- times spent my allowance. Sycamore trees towered in a nearby park, and when their leaves turned penny-colored and crunchy, falling and carpeting the grass, they created the illusion that we lived somewhere that experienced passionate seasons. Santa Maria’s seasons could be hard to detect. The closest we came to getting snow were whispers of frost that half dusted our station wagon’s windshield, hardly enough to write your name in.

Renee Sr.’s face was as gorgeous as my mother’s. The scar above her lip accented her beauty. Above her living room TV hung a framed cross-stitch, God Bless Our Pad. I sat on a black dining room chair in the kitchen, trying to look out the window above the sink. The sky was a boring blue. Cars chugged along Main Street. A gust of wind sent sycamore leaves scattering. Renee Sr. gathered my hair in her hands, winding it around rollers. The ragged cash my mother had paid her was stacked on the kitchen counter. Beside the money, chicken thighs defrosted.

My feet rubbed the spotless linoleum floor. I liked the sensation of my tight socks gliding against it.

“Hold still,” said Renee Sr. “Quit squirming.” Renee Sr. had a perm and an odd, impatient voice. She sounded how I imagined an ant would. Dangerously high-pitched. Venomous.

Once her mother was done setting my hair, a grinning Renee Jr. waved at me, inviting me to her bedroom. I accepted. Renee Jr. had inherited her mother’s beauty, accented by long teeth instead of a knotty scar.

Renee Jr. and I knelt on her chocolate-colored carpet. The apartment, including her room, smelled of buttered flour tortillas and fabric softener. The scent made me feel held, safe, and I couldn’t wait to rinse the perm solution out of my hair so that I could sniff that fragrance again. The stuff Renee Sr. had squirted on me made my head stink and my scalp burn.

Renee Jr. dumped a pile of Barbie dolls between us. Lifting one by her asymmetrical pageboy, I asked, “You’re allowed to cut their hair?”

Renee Jr. petted a blonde and nodded.

“They’re mine,” she said. “I can do whatever I want to them.”

I tried not to act envious. I wasn’t allowed to cut my dolls’ hair or my own. My mother had put that rule in place after I tried giving myself Cleopatra bangs.

With the bedroom door closed, Renee Jr.’s dolls enacted scenes inspired by US and Latin-American soap operas. They yelled, wept, shook, and made murderous threats. They lied and broke promises. They trembled, got naked, and banged stiff pubic areas. Clack, clack, clack. They slapped and bit. They hurt one another on purpose and laughed instead of apologizing. They cheated, broke up, got back together, and cheated again.

They were lesbians. They had no choice.

Renee Jr. had no male dolls.

Renee Jr. carried a distraught lesbian to the open window. I hurried after her.

She shrieked, “I can’t take it anymore! I’m gonna jump!” Silhouetted against the boring blue, we watched the doll go up, pause, and then plummet. Face-first, she smacked the ground unceremoniously.

She’s dead, I thought.

Renee Jr. and I looked at each other. Smiled. We had discovered something fun. Throwing dolls out the window and watching them fall ten stories was something we probably weren’t supposed to be doing. Soon, all of Renee Jr.’s dolls were scattered along the sidewalk beneath her window, contorted in death poses, and we had nothing left to play with but ourselves.

My parents owned a book with glossy reproductions of paintings and drawings by Frida Kahlo. One of the paintings, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, looked like the game invented by Renee Jr.

I was growing out my perm. I liked the one Renee Sr. had given me better than the first one I’d gotten, but I didn’t plan on getting a third. Gilda’s mother and mine were downstairs drinking coffee and gossiping in Spanish. Gilda’s mother spoke Spanish Spanish. She was Spanish and had a challenging nickname. In Spanish Spanish, the nickname didn’t mean anything. It was cute gibberish. In Mexican

Spanish, it meant underwear.

Regina, Gilda’s across-the-cul-de-sac neighbor, was with us. We were gathered in Gilda’s bedroom, and I was wearing a shawl, white wig, and granny glasses. Gilda had told me to put these things on. She said it would make the ghost stories I wanted to tell more realistic.

I rocked in the corner rocking chair, reciting ghost stories until I ran out.

We shared some silence. I continued to rock.

Regina said, “We should play a game.”

I was hesitant. Regina’s games usually led to sudden humping, and I didn’t want to be humped by Regina.

“What game?” asked Gilda. “Delivery room,” answered Regina. “How do you play?” asked Gilda.

Regina said, “Well, there’s three of us, so one of us can be the doctor, one of us can be the pregnant lady, and one of us can be the husband!”

“Okay!” we said.

Regina told Gilda to get a pillow or stuffed animal and stick it under her sweater. Gilda chose a pair of lace-edged pillows and followed instructions, creating a lumpy bulge.

“Looks like twins!” said Regina. She ordered Gilda onto her bed and said, “Spread your legs.” Regina rolled up her sleeves and said, “Ma’am, you’re gonna have to push.” Looking at me, she said, “Sir, you have to support your wife. This is one of the hardest moments of her life. It could kill her.”

I composed myself and fell into my role. I was a married man. I had to support my wife. She could die. The twins could kill her. I hadn’t considered this when I’d gotten her pregnant.

After five minutes of huffing, groaning, panting, and pushing, Gilda gave birth to fat, healthy twins. We rotated roles, quickly realizing that the best role was pregnant lady. The worst was husband. All he did was cheerlead. I gave birth five times. The first two times, my babies survived. The third time, my baby died. We made the corner where the rocking chair stood the cemetery. We had funerals for babies and women who died in childbirth. I died twice.

When was the last time you played a death game?

Were you alone or did you play with others? How much did you trust them?

In Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein postulates that “‘games’ form a family.” To that I would add that players form a family.

The game I played with Renee Jr. is related to the game I played with Gilda and Regina. I mostly trusted the kids I played with, but my guard stayed up around Regina, especially when she was doctor, and I was pregnant lady. Pregnant lady is vulnerable. Doctor is powerful. Danger breathes in the space between them.

From CREEP Copyright © 2023 by Myriam Gurba. Reprinted here with permission from Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

This article was originally published on