28

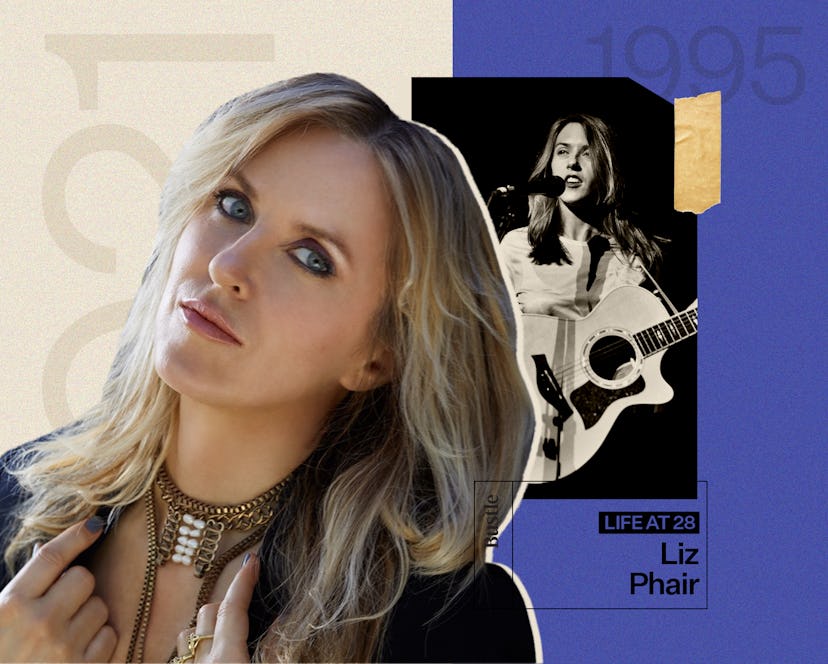

At 28, Liz Phair Traded Rock Star Life For Domestic Bliss

“I had gone from a period of succeeding in my rebelliousness to almost imitating the very thing I was rebelling against.”

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out most, and what, if anything, they would do differently. This time, Liz Phair talks about how she settled down shortly after becoming a successful musician.

In 1993, a 26-year-old Liz Phair was relishing her reign as queen of indie rock. Her album Exile in Guyville had earned praise for its not-quite-grunge melodies and landed her on the cover of Rolling Stone. She was afraid of nothing and no one, roasting pretentious Chicago music dudes and all her ex-boyfriends in one fell swoop with unapologetically frank lyrics like, “You’re going to go down on me, even if it kills you,” from her song “Fuck or Die.”

Two years later, however, a 28-year-old Phair found herself in a very different place: tucked into a new home in Chicago’s classy Lincoln Park neighborhood, cooking dinner for her husband and getting ready to have her first baby. Phair had settled into the kind of domestic life that she had once rebelled against. And mostly, she liked it.

“I was happy in a day-to-day sense, very happy. I was in love, I was going to be a mom, I could afford a house,” Phair, 54, tells Bustle. “And yet at the same time there was this sense of loss... I was aware that not everyone gets an early run at their career like I did, and [I had] that feeling, that quintessential feeling of a working woman. Like, ‘Do I give it up? Do I continue to do it while I'm trying to do all these other things?’”

The complete 180 took some getting used to. She was in the middle of recording her third album, Whitechocolatespaceegg, when she found out she was pregnant. “I had to leave my own recording session because the guys were smoking pot,” Phair says. “It was so strange to be trying to do this same career the same way.”

She still had the fame and critical acclaim, but those accomplishments didn’t necessarily matter in her new world as a wife and expectant mother. So she sat in the quiet. She made new friends. She went up to the tiny studio on the third floor of her home and tried to write about it. “I see Whitechocolatespaceegg as this bridge between childhood and adulthood. It is very evocative of that time in my life,” says Phair. “I think I rushed into changing my life into an adult life but it didn't stick. I wasn't done doing what I needed to be doing.”

In the ensuing decades, wherever she was in her life, Phair made music — and she’s not about to stop anytime soon. Her new album Soberish recalls her Girly Sound days, when Phair was still planning to become a visual artist and secretly recording demos in her childhood bedroom. In Phair’s typical style, the album bares all. Side one details the end of a long relationship and side two is about starting over — something Phair has gotten very good at. “I really can’t look back and say I knew what I was doing at any point in my life,” she says. “But all I ever did was keep trying.”

Below, Phair reflects on her transition to motherhood, and how she continues to balance freedom and stability.

Take me back to 1995, when you were 28.

I was a newlywed, I was pregnant, and I was a new homeowner. There was a huge change in my life from being a single indie rock star... I was queen of the scene in Chicago for a minute there, and then I got married and bought a house in the more conservative Lincoln Park area of Chicago, had a real wedding, and got pregnant — boom, boom, boom, all of a sudden. I had gone from a period of succeeding in my rebelliousness to almost imitating the very thing I was rebelling against in the first place. I was relishing this sort of homebody existence, cooking for my husband when he came home. There was a part of me that was escaping the escape.

Did you have whiplash?

I did. I remember 28 being a very weird year because for the first time in forever I was secure; I was stable. It was both really satisfying, but also the long hours — I just remember the quietness of being pregnant and not being able to hang out with the old gang, who were sort of nighttime club/bar people. If you think about two oceans meeting, I went to a different ocean and all of that stopped for me — all the going out, the nighttime stuff, all the touring, all the band stuff just stopped.

I can remember really loving my body, feeling really good in my body when I was pregnant. And feeling that profound sense of, I had a home, I had a husband, I had a baby on the way, and I’d accomplished something in my 20s. There was a deep satisfaction that I miss — I don't think a week goes by that I don’t raise my eyes and say, ‘God, I wish I could just go home,’ because there is a part of me that wants that security so badly. That is the whiny cry in my soul, I just want to go home.

“I had gone from a period of succeeding in my rebelliousness to almost imitating the very thing I was rebelling against in the first place.”

My mom calls it my home and hearth phase, because it’s tied into that Chicago security — that if you do XYZ this will be secure for you, and I have no security out here [in LA]... Everything is a race out here, everything is competition; unsure. For that freedom of movement you get insecurity, and in Chicago you get security but you don't get the freedom of movement. I wish there was a land that gave us both. Is it okay to want creative freedom and to want security? Is it okay to be that person? I don't know. Twenty-eight was the year of struggling with that, 28 was the year I tussled with that.

I'm still struggling. I’ve learned nothing. All I know is certain places are better for one thing and others are good for others, and I always miss one place when I am in the other place.

You released Exile in Guyville a couple years prior to stellar reviews, a Rolling Stone cover, the works. Did you feel successful and accomplished at 28?

I did not think I was going to be a figurehead. I thought I would make a record that people would be impressed with, but I didn't understand what a life-changing thing it would be. I thought I was going to be a visual artist; I didn’t even know if I was going to continue making music. I think I probably told people I wasn't. But I missed it.

At that point, did you feel respected in the Chicago rock scene?

In one sense, I felt respected by the general population — they had seen and read about me, but I also felt that people were debating my worthiness for that acclaim in the art scene. Still to this day when I go back to Chicago on tour, it’s one of the places I get my worst reviews, which is really f*cking weird. I count on it, I tell everybody it’s going to happen, and lo and behold it almost always happens. I get reviewed more harshly in my hometown than I do anywhere else in the U.S. I don’t know what that says, but I could feel that at that time. I talked to Billy Corgan about that — there is something about Chicago that’s like if you leave, it’s a weird thing.

[In] LA, nobody knows where everyone is from, or who’s here or there, it’s all just water under the bridge. In Chicago, there is a real sense of, “I’m from Chicago and I root for the Sox or the Cubs.” There’s loyalty; there’s organization in the social structure that there just isn't in other places.

What did a night on the town look like for you at 28, before you were pregnant?

It was a game of chase... I always had a crush on someone. I would find out who was in town, if there were any bands that I liked, and I’d either go with someone or I’d agree to meet someone there, or I’d go by myself and make friends with people at the show, or see people I knew. Then I’d find out where they were going next, see if I could get backstage, see if there were any drugs to do, find out where the party was going to be or if we were going to a bar. Then, I’d go to that bar or party or wherever and make friends there. I was excellent at making friends. You could literally toss me into any party anywhere anytime and I will cold do the party.

I'm still the same exact way, this is what’s so funny — it wasn't about being 27 or 28, that’s me. When [my son] Nick went to college we would do the same kind of night out only with more people, and we can connect via our phones. I don’t think when I go out here in Los Angeles that I go anywhere fewer than three places in a night at least, maybe five... I wanted to have an epic night every time I went out, and I have a pretty good ability to make that happen.

What advice you would give your 28-year-old self?

I wouldn't change anything, because I wouldn't have had my son and I wouldn't have had the life I had. But I'd like to tell myself — and I'd like to tell everyone — that society wants you to hit certain marks, certain milestones, at certain times, and that can be a double-edged sword. A lot of people think of it as a game of musical chairs: you just have to sit down, there are not that many chairs left. That part of it I don't think was helpful, and it ended up getting me in trouble because I don't think I was ready to sit down.

The most useful thing I can impart, thinking back on 28, is no matter what your circumstances are, there is a way to make art through it. I never knew what I was doing in my career. I might have had a plan for these six months and said what I wanted to do, but all I ever did was keep trying to do the thing I want to do. That's all I ever do.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on