Books

Being Gay Doesn’t Have A Uniform. But RuPaul’s Drag Race Helped Me Find Mine.

John Paul Brammer explains how to dress in silks and linens.

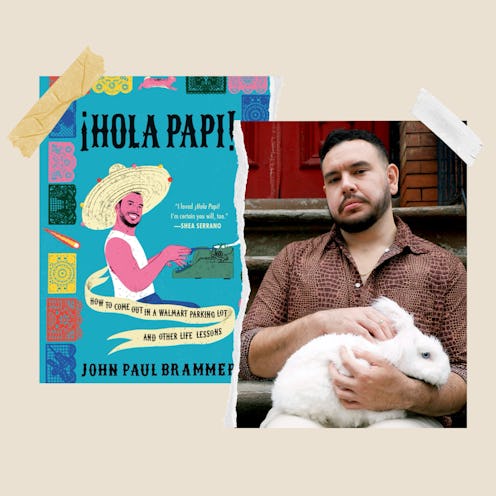

In this chapter excerpted from his new memoir, ¡Hola Papi!: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons, writer and advice columnist John Paul Brammer discusses how he learned to express himself and his sexuality through clothing.

¡Hola Papi!

I want to dress gayer, but I’m afraid. What do I do?

Signed,

Boring Closet(ed)

My mom used to take me shopping with her. We’d drive up to the mall and go to Dillard’s, the nicest department store in town, or sometimes we’d even go to Wichita Falls, Texas, for more options. My mom had a discerning eye for fashion that she’d brag about. “I was poor, but I had good taste,” she’d often said of her childhood. “It doesn’t matter how much money you have. You can have good taste.”

I’d watch her rifle through the clothing rack and make her judgments by some mysterious criteria. I’d wait for her outside the changing room, holding her purse. She’d come out, pressing the garments to her body to feel them out, checking herself in the mirror. “What do you think?” she’d ask.

I loved these trips to the mall, Boring. I loved the idea of taste, the notion that I could hold some authority over distinguishing good from bad. It was like a game, and I got hooked very early. But it was a complicated addiction knowing that I was supposed to hate these outings. On one hand, I loved judging my mom’s outfits, though my opinion wasn’t worth half as much as she let me believe. I loved looking at the mannequins, the elegant articulation of their hands, their statuesque confidence, the stories they told with their clothes — a trip to the beach, lunch with her shady friends while their wealthy husbands were at work, a cocktail party where she was to seduce a prince.

But this fantasy world was not meant for me, a boy. My clothes were not meant to tell such stories. All they would ever say is, I am a boy, and here I am. I am a boy at a wedding. I am a boy at school. I am a boy, and this is my shirt, thank you. My options were limited to the “Husky Kids” section of Walmart, where I could adorn myself in such evocative fashions as a T-shirt that said NORMAL PEOPLE SCARE ME on the front and boot-cut jeans. I was in hell, Boring. I was Tantalus, the Greek mythological figure made to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree, the water always receding before he could take a sip, the fruit ever eluding his grasp. I could look at the treasures before me, but I couldn’t partake. In fact, I was meant to pretend I hated the whole idea of clothing and accessorizing. That was “girl stuff.”

Yet there I was, the cliché closeted gay boy harboring a secret love of fashion, hiding my mom’s copies of Vogue under my bed. But it wasn’t just the clothes that drew me in, Boring. I was attracted to the idea that there was another way to go about life, one in which I was better equipped to thrive. My present criteria expected me to play sports and not cry, so I was failing.

I liked this foreign world that troubled itself with superfluous details. It was the domain of fierce women and harried men of an alternative masculinity who wore ridiculous garments and made crises out of little things like length, fit, and accessories. I imagined it as a sort of play world where everyone was acting and dressing up. They could have called off the act at any time, surely, but they were having too much fun pretending.

Glimpses into the world of high fashion came to me through my mother’s magazines and America’s Next Top Model, which we watched religiously together on the couch and where flamboyant men were always screaming at skinny women to bend their backs more. I’d privately fantasize about Tyra Banks’s coming to our tiny town to scout for new models for the junior version of her show that didn’t exist. She’d see me, ugly, but so ugly that I was in possession of a unique kind of beauty — interesting to look at — and she’d cart me off to do a photo shoot. That was definitely how reality television worked.

But my reality was utterly inhospitable to my interests. Cache wasn’t exactly a hotbed for sartorial innovation; once, a kid wore a Hollister shirt to school — a chocolate-brown knit shirt with the red Hollister seagull on it — and initiated the trial of the century. “Isn’t that for gay dudes?” he was asked. “Isn’t Hollister a gay-guy thing?” I never saw the shirt again. Another time, a kid who everyone suspected was gay dared to describe his plaid button-up shirt as “cute.” He was compelled to transfer schools the next year.

Instead, I held secret space in my brain for my passions — drawing, sewing, accessorizing, visions of tall buildings with shiny tiled floors and vicious women in oversized sunglasses and fur coats. I was an imagined citizen of that secret place. I was some magazine editor’s exhausted, overworked assistant, scrambling to put together an outfit for the big launch party the next day.

I don’t know what happened to that world, those offices in my mind. Maybe all the years in Satan’s Armpit, Oklahoma, finally wore me down. At some point, I gutted them and replaced them with things that made more sense: a subdued interest in Tarantino, a highly public appreciation for video games. In high school, I dressed like a parody of a straight Mexican kid with anger issues. I wore loose jeans and baggy shirts that reflected approximately zero of my interests: Mexican soccer teams and wrestlers and platitudes that catered to athletes, slogans like JUST DO IT or PROTECT THIS HOUSE. What house? What was this house, who lived there, and why had I been tasked with protecting it? All moot points. The point was to look like I didn’t care about clothes.

That’s the paradox of lazy masculinity, Boring. All clothing is selected with some degree of care, even the clothing I was wearing. I wanted to look apathetic and masculine, which required a concerted effort from my costuming department.

It wasn’t until years later when I was introduced to RuPaul’s Drag Race as a senior at the University of Oklahoma that I began to think of clothing as a vehicle for self-expression. I’d found two older gay guys to take me under their wing; Drag Race was part of my required viewing. Sitting on the living room floor surrounded by other gay guys in wigs, I watched with some trepidation as men transformed themselves into visions, using makeup and sewing machines. What emerged wasn’t a woman, necessarily, but an aesthetic assertion of glamour, or comedy, or anything, really. My takeaway was to consider clothing as a language, a visual vocabulary with which one could speak: “I’m giving the judges ‘Helen of Troy if she were a lesbian mall goth.’” That was something one could communicate, if one wanted to, with a curated selection of garments. It made me wonder if I had anything I wanted to say.

I began to take my interest in fashion more seriously. I openly delighted in shopping instead of pretending to dread it as I had in my youth. I read up on textiles, leather goods, and what constituted “quality.” I stepped into dressing rooms and tried everything on, appreciating the hypothetical futures each outfit illustrated. I would wear this on a nice date. I would wear this on a vacation to the beach. Each one had the capacity to make me a certain kind of person, a new person, whom I could step into and move through the world as.

I was excited and content with this masquerade for a while. Then I moved to New York.

My first roommate in New York was a circuit queen who occasionally hosted queer parties. He knew I wasn’t a big party person — it was hard for me to stay out past one a.m. without blinking to stay awake — but he wanted to show me what I was missing out on. “It will be cute,” he promised.

The party was called Holy Mountain, or HoMo. I’d watched enough Drag Race to know that the occasion called for a look, a showstopping fashion moment. But I didn’t have anything in my closet that even came close to being a look. I selected my most eccentric piece, which, at the time, was a black leather harness I’d purchased because I was filthy first and an aesthete second. I wore it over a mesh black shirt. My roommate stirred up some pre-workout (drinkable cocaine) to amp us up and we drank it out of plastic cups on the M train to Manhattan. When we arrived, I immediately realized I was just a straight-looking bro in a harness.

I saw some wild shit, Boring. I’d seen outfits like these on TV, like on Drag Race. But that was TV. Tyra was never really going to jump out of the screen and ask me to pose for a photo. But here, at HoMo, it was actually happening: capes and catsuits and acrylic nails and shoulder pads and makeup like you’d see in a fantasy movie. I’d stepped into another world, a world where the hierarchies had been turned upside down and aesthetic queerness was aspirational. Passing as heterosexual, which had once been my only goal, was considered bland in this little corner of the world. I took quick stock of myself, Boring, and realized I was dull as hell.

I admit it felt a little unfair. How was I to know that the fantasy world I’d lusted over as a kid had been real all along? If I had known, if I had only known, I would have adjusted accordingly. I would have invested in the statement jewelry and the billowy tops and the platform shoes I’d admired from a distance. This was all homework I’d neglected, because I’d been so busy pretending to be straight. Years and years denying myself the things I’d wanted, and for what? To end up as some guy who thought a pair of chinos in a “fun” color was the epitome of fashion? My God. I was downright fratty.

Who, exactly, had been stopping me? In truth, no one had ever explicitly told me not to wear the things I’d wanted to wear. My parents, overall, were accepting people. Hell, looking back, my mother had all but deliberately raised a gay son.

So who, exactly, had been holding me back from being the person I’d wanted to be, and was that person in fact myself? And did this extend beyond clothing? Was this the case with the men I liked and had dated, with the interests I held and the way I spoke? Had I been mistaking other people’s desires for my own all this time? I woke up the next day in my Brooklyn apartment with a hangover and an existential crisis. I need to get so much gayer, I thought. I went shopping as soon as my next paycheck came in.

I hit up Topman first. It wasn’t exactly the boldest direction, but in truth I had no idea where the mirages I’d seen at HoMo had sourced their duds. Was there a secret store that sold capes and mesh crop tops, and if so, where was it? Or was every gay person in New York also a designer with a sewing machine? I hadn’t a clue, but I did know I’d seen some long, flowing garments in Topman before, having averted my eyes to more moderate options. It was time to revisit and take a deliberate risk.

I took the escalator down to the bottom floor. There they were, shawls and wraps and other sorts of wispy, silky items. In the solitude of the fitting room, I slipped an oversized, draping shirt over my head. I checked myself out in the mirror and felt like the world’s biggest idiot. My body, wide shouldered and fatally masculine, felt clunky and incorrect in the delicate garment. There was no beauty, no exciting imagined future for me to step into — going to the club, going back to HoMo, sitting down for drinks; there was none of that delicious illustration in it. There was just me: a thick, hairy man with a sweaty back in a witchy slip, playing dress-up. People would look at me, and they would laugh.

I still bought it.

I hoped that the daring act of buying it would change something in me, bring me closer to the kind of person who bought these sorts of clothes and then wore them. It would take time, I told myself, to undo everything I thought I knew. I was a gay writer in New York. I knew all the rhetoric — “internalized homophobia,” “toxic masculinity” — I knew I’d supposedly been stewing in these concepts my whole life and that my thoughts had been shaped by them. I knew that looking at my bigger body as inherently masculine was a problem. I knew that the fear I felt while wearing something feminine came from the stigma of all things feminine. But knowing this didn’t help. It didn’t change the way I reacted to that stupid article of clothing, the way it felt like the shirt itself wanted nothing to do with me.

The blousy top stayed in its bag in my closet for weeks, shaming me with its disuse. Invitations for more parties came and went, and sometimes I did go, but I always fell back into my comfort zone of the harness. I admonished myself every time, telling myself that at some point, I would have to stop caring what other people thought. But walking to the parties with my roommate, who was always wearing something extravagant and had a face full of makeup, watching the way people reacted to him, I wondered if I would ever marshal the courage.

Unsafe. I discovered, Boring, that what I felt was unsafe. People’s glances made me feel unsafe. I knew the capacity for violence that lurked behind people’s eyes. I knew it from middle school, where I’d let people bully me out of my own existence. I would look at myself through their eyes sometimes, scanning for openings, a preemptive measure, no doubt. I would look at myself with their gaze, and what I saw held language, not words, really, but language — You are wrong. You are pathetic. You are deserving of judgment and violence.

I’d developed this lens as a means of protecting myself, Boring. Both as a fat kid and as a closeted young gay person, I developed a relationship with the space around me that was inherently adversarial. My job was to minimize the space I took up, as space was just real estate where violence could land — fat jokes, gay jokes, general punishment. It was better, always better, to shrink, to be small in appearance and in nature, to be as little as I could to give people fewer chances.

I’d shaped myself to accommodate this gaze, this eye that lived in my head and was constantly looking: within myself for errors and then without for potential threats. I would walk quicker if a rambunctious crowd of men was approaching. I would take off my jewelry and slip it in my backpack if I was walking home at night. I would go everywhere with my earphones in and my head held down, hoping no one would look at me, because being looked at was a vulnerable thing, an invitation. I was a walking statement, and I thought it prudent to, as best as I could manage, say as little as possible.

And yet, here in New York was a community, a whole world, where being loud was a virtue. I wanted desperately to join their conversation.

Even if I gathered up the courage to wear something gayer, Boring, my body would still be wrong. The beautiful people who wore these extravagant looks were thin, lithe gazelles. Then there were the men who wore next to nothing, who could just show up in jockstraps and eye shadow. They were muscular and impossibly fit. Why would I even bother adorning a body like mine, a body that wasn’t distinct in any laudable way?

“Fabulous,” my mother used to say when she found an outfit she particularly liked. My mom had this regal way of walking, her heels clacking from a mile away. When I think of power, that nebulous concept, I think of that sound. I would imagine what it might be like to embody it, to make a sound like that myself, to have people know when I was coming.

Fashion is a lexicon, Boring. It’s a storytelling technique. Everything holds a message. Everything has something to say about the world we live in — and I found that, in the way I was dressing, in the way I was presenting, I wasn’t speaking my mind. I was apologizing. I was tired of that. I wanted to feel powerful in the way that I defined power. I wanted to be like my mom clomping down the hall in heels. I wanted to be like the queers at HoMo, audacious but in my own way.

It wasn’t so much clothing itself I wanted, an unmet desire to “buy stuff.” It was a mode of being that I sought: a freer method of movement.

Being gay, queer, or whatever you’d like to call yourself doesn’t have a uniform. There’s no such thing, I’ve found, as “dressing gayer” or “looking gayer.” You don’t have to dye your hair or paint your nails. It’s more important to interrogate the gaze with which you behold yourself. Whose gaze is it, and what is it looking for, Boring? What might it be like to have a lens that is more your own?

It’s not about buying things or reducing queerness to commercial goods, or even down to aesthetics. It’s about the relationship between presentation and identity, recognizing that our bodies exist in conversation with the world and asserting autonomy over what we’re saying in it, even against the threat of violence. I found that in other forms of speech, in my writing, for example, I had no problem speaking up for myself and for others. I can only imagine what it might have been like if, in those glossy pages of Vogue, I had seen anything approaching the visions of myself that I held close and secret. I wish that, through visuals, someone had communicated that it was okay for me just to think about myself that way, not even necessarily to be that way, but to merely expand my horizons. I think that’s why it’s important that we express ourselves: you never know who might be listening and who needs to hear you.

Expression, be it verbal or nonverbal, is how we articulate ourselves to the world. It can bring us into closer alignment with the complexity of our interiors, which are too great and too confusing to ever be brought entirely under the sovereignty of language. But in trying, it can help us make connections. At least, thinking that way made me feel better about blowing over $100 on this beautiful linen top. It doesn’t have a collar, Boring. Isn’t that cool? It’s like a robe I can wear outside. I discover new possibilities every day.

From HOLA PAPI: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons by John Paul Brammer. Copyright © 2021 by John Paul Brammer. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.