Books

Exclusive: Joan Didion Writes On One Of Her Earliest Experiences With Failure

In an excerpt from her newest essay collection, Let Me Tell You What I Mean.

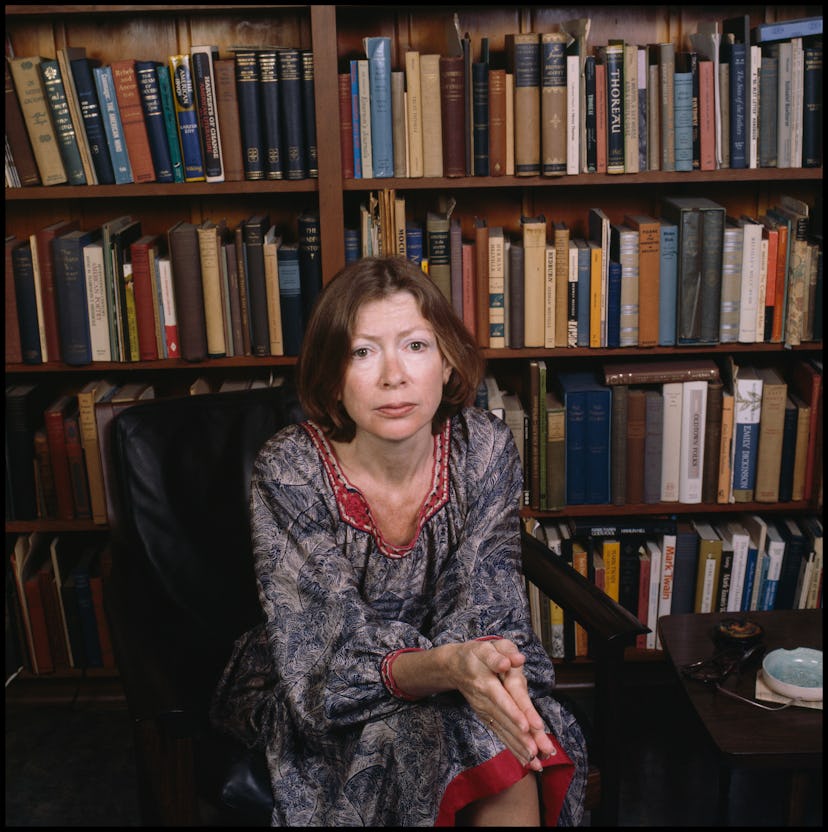

Joan Didion has long been lauded as the voice of her generation. The 86-year-old writer has won the National Book Award, been a Pulitzer Prize finalist, and was given the National Humanities Medal by President Obama. But before she became the patron saint of literary girls — or Céline's most celebrated model — Didion was just a young Sacramento native, eagerly awaiting an acceptance letter to Stanford that would never come. This experience is just one of the many Didion chronicles in her latest essay collection, Let Me Tell You What I Mean.

This new book contains 12 previously uncollected Didion essays, all written between 1968 and 2000, which touch on everything from the writing life to the meaning of Martha Stewart's success. "On Being Unchosen by the College of One's Choice," which is excerpted below, delves deep into the author's early collegiate setback. In it, Didion reflects on being denied admission to Stanford and spending a wayward summer grappling with her feelings of rejection.

The book isn't out until Jan. 26, but you can start reading this excerpt from Joan Didion's Let Me Tell You What I Mean today, exclusively on Bustle:

On Being Unchosen by the College of One's Choice

"Dear Joan," the letter begins, although the writer did not know me at all. The letter is dated April 25, 1952, and for a long time now it has been in a drawer in my mother's house, the kind of back bedroom drawer given over to class prophecies and dried butterfly orchids and newspaper photographs that show eight bridesmaids and two flower girls inspecting a sixpence in a bride's shoe. What slight emotional investment I ever had in dried butterfly orchids and pictures of myself as a bridesmaid has proved evanescent, but I still have an investment in the letter, which, except for the "Dear Joan," is mimeographed. I got the letter out as an object lesson for a seventeen-year-old cousin who is unable to eat or sleep as she waits to hear from what she keeps calling the colleges of her choice. Here is what the letter says:

The Committee on Admissions asks me to inform you that it is unable to take favorable action upon your application for admission to Stanford University. While you have met the minimum requirements, we regret that because of the severity of the competition, the Committee cannot include you in the group to be admitted. The Committee joins me in extending you every good wish for the successful continuation of your education. Sincerely yours, Rixford K. Snyder, Director of Admissions

I remember quite clearly the afternoon I opened that letter. I stood reading and rereading it, my sweater and my books fallen on the hall floor, trying to interpret the words in some less final way, the phrases "unable to take" and "favorable action" fading in and out of focus until the sentence made no sense at all. We lived then in a big dark Victorian house, and I had a sharp and dolorous image of myself growing old in it, never going to school anywhere, the spinster in Washington Square. I went upstairs to my room and locked the door and for a couple of hours I cried. For a while I sat on the floor of my closet and buried my face in an old quilted robe and later, after the situation's real humiliations (all my friends who applied to Stanford had been admitted) had faded into safe theatrics, I sat on the edge of the bathtub and thought about swallowing the contents of an old bottle of codeine-and-Empirin. I saw myself in an oxygen tent, with Rixford K. Snyder hovering outside, although how the news was to reach Rixford K. Snyder was a plot point that troubled me even as I counted out the tablets.

Of course I did not take the tablets. I spent the rest of the spring in sullen but mild rebellion, sitting around drive-ins, listening to Tulsa evangelists on the car radio, and in the summer I fell in love with someone who wanted to be a golf pro, and I spent a lot of time watching him practice putting, and in the fall I went to a junior college a couple of hours a day and made up the credits I needed to go to the University of California at Berkeley. The next year a friend at Stanford asked me to write him a paper on Conrad's Nostromo, and I did, and he got an A on it. I got a B — on the same paper at Berkeley, and the specter of Rixford K. Snyder was exorcised.

So it worked out all right, my single experience in that most conventional middle-class confrontation, the child vs. the Admissions Committee. But that was in the benign world of country California in 1952, and I think it must be more difficult for children I know now, children whose lives from the age of two or three are a series of perilously programmed steps, each of which must be successfully negotiated in order to avoid just such a letter as mine from one or another of the Rixford K. Snyders of the world. An acquaintance told me recently that there were ninety applicants for the seven openings in the kindergarten of an expensive school in which she hoped to enroll her four-year-old, and that she was frantic because none of the four-year-old's letters of recommendation had mentioned the child's "interest in art." Had I been raised under that pressure, I suspect I would have taken the codeine-and-Empirin on that April afternoon in 1952. My rejection was different, my humiliation private: no parental hopes rode on whether I was admitted to Stanford, or anywhere. Of course my mother and father wanted me to be happy, and of course they expected that happiness would necessarily entail accomplishment, but the terms of that accomplishment were my affair. Their idea of their own and of my worth remained independent of where, or even if, I went to college. Our social situation was static, and the question of "right" schools, so traditionally urgent to the upwardly mobile, did not arise. When my father was told that I had been rejected by Stanford, he shrugged and offered me a drink.

I think about that shrug with a great deal of appreciation whenever I hear parents talking about their children's "chances." What makes me uneasy is the sense that they are merging their children's chances with their own, demanding of a child that he make good not only for himself but for the greater glory of his father and mother. Of course it is harder to get into college now than it once was. Of course there are more children than "desirable" openings. But we are deluding ourselves if we pretend that desirable schools benefit the child alone. ("I wouldn't care at all about his getting into Yale if it weren't for Vietnam," a father told me not long ago, quite unconscious of his own speciousness; it would have been malicious of me to suggest that one could also get a deferment at Long Beach State.) Getting into college has become an ugly business, malignant in its consumption and diversion of time and energy and true interests, and not its least deleterious aspect is how the children themselves accept it. They talk casually and unattractively of their "first, second, and third choices," of how their "first-choice" application (to Stephens, say) does not actually reflect their first choice (their first choice was Smith, but their adviser said their chances were low, so why "waste" the application?); they are calculating about the expectation of rejections, about their "backup" possibilities, about getting the right sport and the right extracurricular activities to "balance" the application, about juggling confirmations when their third choice accepts before their first choice answers. They are wise in the white lie here, the small self-aggrandizement there, in the importance of letters from "names" their parents scarcely know. I have heard conversations among sixteen-year-olds who were exceeded in their skill at manipulative self-promotion only by applicants for large literary grants.

And of course none of it matters very much at all, none of these early successes, early failures. I wonder if we had better not find some way to let our children know this, some way to extricate our expectations from theirs, some way to let them work through their own rejections and sullen rebellions and interludes with golf pros, unassisted by anxious prompting from the wings. Finding one's role at seventeen is problem enough, without being handed somebody else's script.

1968

Excerpted from LET ME TELL YOU WHAT I MEAN by Joan Didion. Copyright © 2021 by Joan Didion. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.