TV & Movies

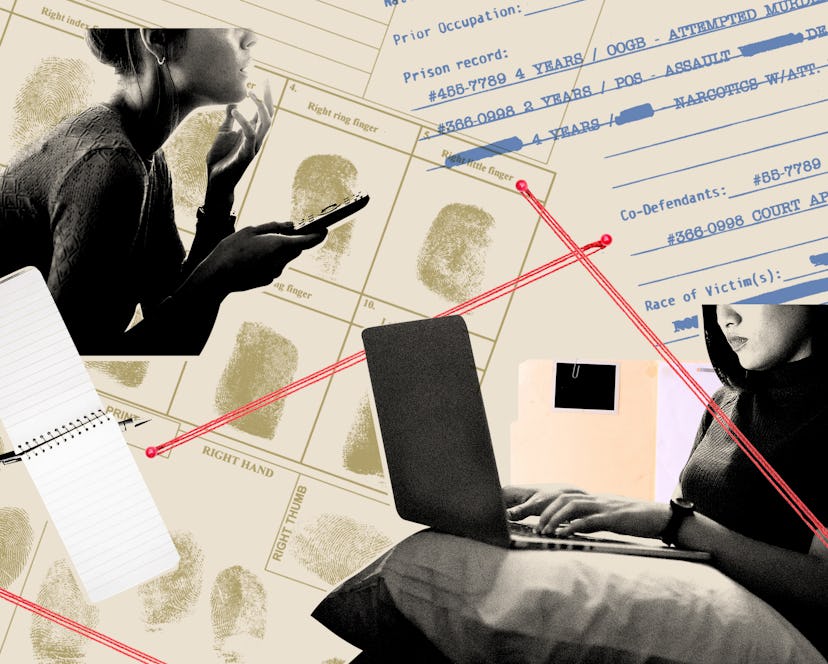

What It’s Like To Spend A Decade Hunting A Serial Killer On The Internet

How two internet sleuths ended up at the center of the hunt for the Golden State Killer.

Paul Haynes was 28 when he first found himself on A&E’s Cold Case Files message boards, scanning through other viewers’ theories about the show’s unsolved crimes. He’d been a film major in college but ended up unemployed and living back at home in South Florida, feeling defeated. “I was spending most of my time in my room, so I kind of was that loner in the veritable basement,” says Haynes, who, with a detective's insistence on detail, points out that South Florida homes don’t actually have basements. Eventually, he started chasing down leads and posting himself. “I found myself drifting into doing it 10 to 15 hours a day. There was a clear end goal, you know? To identify [the] offender.”

As a child, Haynes watched Unsolved Mysteries and read locked-room mystery novels voraciously. He’d dipped a toe — “never anything more than a toe” — into a handful of cold cases before discovering the EAR/ONS forums, named for the Sacramento serial rapist known as the East Area Rapist, who turned out to be the same perpetrator behind the Southern California murders credited to the Original Night Stalker. After helping a friend track down an eBay scammer, Haynes realized he had a knack for digital sleuthing. He agreed to build a reverse city directory for the webmaster of Ear-ons.com, zooming in on the neighborhood where a single attack had occurred decades earlier. It only took him 20 hours to figure out. After months of feeling depressed, Haynes had a sense of purpose. “I felt like what I'm doing could actually lead to the offender’s identity.”

Through the A&E forums, Haynes met his future collaborators: school community worker Melanie Barbeau and the late author Michelle McNamara. It was McNamara who re-christened the East Area Rapist the Golden State Killer, and whose years-long hunt for the criminal now serves as the subject of HBO’s docuseries I’ll Be Gone in the Dark. Haynes knows true crime forums are an odd way to make friends. Citizen detectives, armchair sleuths, websleuths — he’s uncomfortable with all the shorthands that describe the dark hobby that introduced them.

It’s understandable that Haynes wants to distance himself from the predominant images of true crime enthusiasts as bored housewives or fervent conspiracy theorists. In recent years, citizen detectives have made some high-profile blunders: after the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, eager Redditors misidentified several innocent people as suspects, including missing person Sunil Tripathi, whose body was found a week later. And in 2017, web detectives misidentified the man who drove his van into a crowd outside British Parliament — an accusation retweeted (and later deleted) by Donald Trump, Jr. Amateur detectives operating with diffuse responsibility can be quick to go public with unsubstantiated theories; to see connections where none exist.

Haynes and Barbeau aren’t oblivious to the problems inside the online crime-solving community; in fact, they point out new ones. There’s a tendency on the forums to prefer fanciful explanations to straightforward ones. For example, to read burnt matches lying beside a victim’s body as symbolically significant. “The offender may have just been trying to see his way in the dark,” Haynes says. Barbeau, who grew up in Sacramento at the same time the Golden State Killer was active, saw herself as a rigorous fact-checker on the forums. She and Haynes weren’t there to wildly speculate or pass some time — they really, really wanted to catch the guy.

For Barbeau, a sexual assault survivor whose attackers were never arrested, it was a form of healing. “People don't recognize... how our own trauma pulled us into this,” she says. She’d stay up until all hours of the night hunting the GSK after putting in full days at work. “I felt like I was doing a service for my community."

And she was. In I’ll Be Gone In the Dark, based on McNamara’s 2018 book of the same name, the evidence the three dug up doesn’t solve the case, but it does keep the police from letting the trail go cold. Barbeau, who is featured in the series, thinks of herself as a “slight thorn” in the side of the official investigation, urging it on; Haynes, an executive producer on the project, calls citizen detectives “ankle biters.”

"There’s a tension between the gravity of the project — to solve crimes that happened to real people — and how distracted the conversation can become by petty squabbles."

Of course, not all websleuths are as single-minded. Upon signing up for the popular site Websleuths.com, which has nearly 9,000 registered accounts, users receive a message reminding them of the rules of decorum: no name calling, no foul language. Still, violations are common and banned members frequently take to other sites to complain about their dismissals. Like all subcultures, websleuths have evolved their own mores and hierarchies. There are verified users and trophy points for attracting "likes." But reading the screeds of people who feel wronged by the moderators is troubling. There’s a tension between the gravity of the project — to solve crimes that happened to real people — and how distracted the conversation can become by petty squabbles. Even Barbeau, who is adamant that the GSK’s victims were always at the forefront of her mind, has regrets about her conduct on the A&E boards. “I wish I might've been kinder or I might've considered other people's feelings more than just trying to advance with my information.”

Nowhere is this kind of insolence more apparent than on Etsy, where true crime occupies a pretty glib corner of the slogan tee market. Popular offerings include “The Husband Did It” and “True Crime, Glass of Wine, In Bed By Nine.” “I’m Only Here To Establish My Alibi” has already been turned into a face mask. There’s something undeniably unsavory about the monetization and the gamification of unsolved murders.

There’s also an upside. In 2018, Haynes was a panelist at CrimeCon, a three-day convention hosted by the Oxygen network, which airs Killer Couples and Accident, Suicide, Or Murder and the podcast Murder & Martinis. “It’s a double-edged sword. You're bringing these cases into a much broader level of public awareness and that's doing a service to the cases,” he says. And despite some of the dissidence among members, the Websleuths.com community has been particularly effective at identifying missing persons.

The more popular true crime gets, the more interest grows in moonlighting as a citizen detective. It’s no longer the narrow community Barbeau remembers from the early 2000s. When Netflix rebooted Unsolved Mysteries, the same series that hooked Haynes as a kid, it went even further than the A&E message boards did to create community around the show, sharing the case files, interviews, and evidence uncovered during production on Reddit for citizen detectives to analyze. That subreddit alone has a quarter of a million followers. In 2021, Oxygen, which rebranded itself as a true crime TV network in 2017, will host its first-ever CrimeCruise, a true-crime themed vacation to the Bahamas.

Despite how mainstream true crime has become, it’s hard for Haynes and Barbeau to imagine investing in another case now that the GSK has finally been caught. Haynes, now 38, says he’s grown disconnected from the community. Barbeau remains a little more involved. She talks regularly with her sleuthing “teammates,” who she calls Port and Arch to safeguard their anonymity. “I got off the phone with Port about an hour ago. We talk every day. We're like sisters, and we've never met,” she says. And maybe it’s a force of habit, but she checks the GSK message boards from time to time. “I don't know why. There's nothing for me really there because this is solved.” As it is, Barbeau can’t believe how involved she became with the GSK case over the last dozen years. “I don't think I'm interested in any other cases,” she says. Still, she can’t bring herself to shut the door entirely. “It would have to be something that really called me.”

This article was originally published on