Books

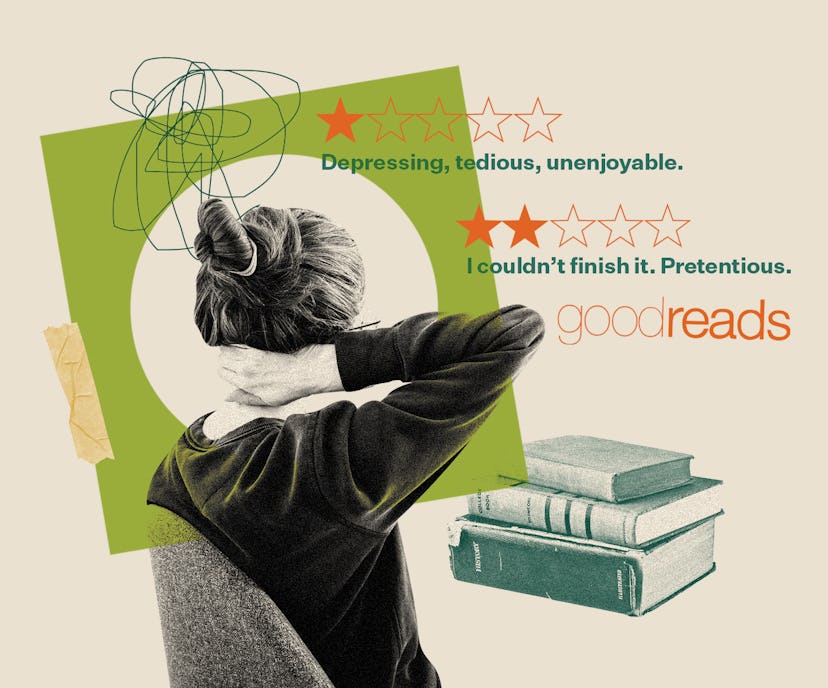

Goodbye To Goodreads

After negative Goodreads reviews started to affect author Jessica Goodman's editing process, she decided to stop reading the site. Other authors have come to the same conclusion.

I still remember a one-star review my first novel got on Goodreads. It simply said, “The problem with this book is that it’s bad.”

At least I think that’s what it said. I haven’t looked at it since I saw it, slammed my laptop shut, and yelped out a laugh. I mean, it was objectively funny — a staccato declaration that couldn’t help but incite admiration even though the person on the other end of the keyboard did not like my work.

But finding that comment was also the moment that made me decide it was time to stop reading online reviews on sites like Goodreads and Amazon, where anyone with internet access can leave critiques and numerical ratings of books. Social media would be harder to avoid, of course, but maybe I’d try to stop reading reviews on those platforms, too. It was a good idea. Fruitless, but good. Because authors now exist in a world where book coverage has shriveled at almost every major news outlet, professional reviews are few and far between, and in-person events rarely if ever take place these days thanks to the pandemic. As a result, most of the feedback we get these days comes from open-access online platforms where armchair critics abound. This ecosystem has caused so many authors to ask themselves the question: Should I read all my reviews?

“It took a lot of me being burned to decide that [reading most non-professional criticism] was not good for me,” says Andrea Bartz, author of psychological thrillers including We Were Never Here, which was selected as a Reese Witherspoon book club pick this summer. “It was preventing me from being able to focus on promoting my work and creating the next book, which is one of the most important things.”

Bartz is right. There was a time when I read every single review, positive or negative, of my young adult thrillers. But after a while, I couldn’t let go of specific comments from people I didn’t know telling me things like my stories were “slow in the beginning.” That feedback made me obsessed with picking up the pace in a novel I was editing. But instead of making the story better, my editor, whose opinion I worship, told me I was rushing the character development. It dawned on me then that perhaps maybe I shouldn’t listen to every single piece of commentary.

“I really only take the feedback of people I trust and value,” says Chloe Gong, author of the YA fantasy duology These Violent Delights. “My agent, my editor, my friends. I've forced myself to internalize the fact that their opinions are what I will let affect my creative process. The other opinions, I try to make them white noise as much as possible.” Her solution has been to avoid seeking out online reviews — “out of my own sanity and mental protection.” She says, “I usually only read the things that people tag me in.”

“I'm always surprised when I'm tagged in a mean review because I'm like, ‘You know that I'm a real person on the other end of this Instagram, right?’”

But when tagged reviews get nasty or critical, which, yes, definitely does happen, they can feel oddly personal, especially since most authors manage their own social media accounts and don’t meet the level of celebrity of, say, a film or pop star. “I'm always surprised when I'm tagged in a mean review because I'm like, ‘You know that I'm a real person on the other end of this Instagram, right?’” says Bartz.

Receiving a barrage of online responses has caused Zakiya Dalila Harris, author of The Other Black Girl, a Good Morning America book club pick in June, to “linger less on things I’m tagged in.” She says, “I may read a little but generally I don't read the full thing. I might still share it though, because this person engaged with [my book]. I do want to acknowledge that.”

And yes, a lot of times, online dialog with readers can be good — even great. When my debut novel, They Wish They Were Us, came out in August 2020, I was hungry to connect with readers, especially since I felt so isolated during the pandemic. Seeing positive posts about my work gave me great pride and motivated me to finish my second book, They’ll Never Catch Us.

“If readers love my books, and they just want to chat a few sentences on Twitter, I love providing that,” says Gong. “It outweighs the negatives of being accessible for people who want to tag me in opinions I don't necessarily need to hear. It's a constant battle.”

Harris agrees: “Even though I've read things that were not great, I also will sometimes take screenshots of the really sweet notes I get from strangers, especially Black women who just say thank you, or that they felt seen in my book. That feels so good and reminds me who I was writing for.”

“I also will sometimes take screenshots of the really sweet notes I get from strangers, especially Black women who just say thank you, or that they felt seen in my book. That feels so good and reminds me who I was writing for.”

Yet this kind of consistent accessibility can harm authors, who can easily become burnt out on the expectation that they should constantly be engaging with readers and other authors in order to promote their books. “It’s not like most of us get huge marketing budgets,” says Leah Johnson, author of YA romances Rise to the Sun and You Should See Me in a Crown, the latter of which was Reese Witherspoon's first YA book club pick in 2020. That causes authors to spin their wheels, planning giveaways, Instagram Lives, Reddit AMAs, and other social media moments that authors hope will spread the word about their books. After releasing two books during the pandemic, Johnsons advises, “You don't have to be online 24/7 in order to sell your books. If it begins to feel like it's too much, log out.”

That pressure to be online also opens authors, specifically authors of marginalized identities, to receive hate speech. “The internet ideally acts as the great equalizer,” says Johnson. “It gives people who have never had a chance to have their voices and opinions heard, elevated and uplifted.” But as a Black, queer, female author, Johnson has also faced vitriol couched as reviews of her work, which star Black, queer, young women. “I made a decision to have a public facing career. And so, that means people have public opinions about how I behave. But I'm also hyper-aware of the fact that if I weren't me, if I did the same things I do, but lived in a different body, then I would not face the types of criticisms about my work that I face.”

Since becoming a published author in June 2020, Johnson has mostly avoided reading reviews and has changed her relationship to social media, picking and choosing where to spend her time and energy in order to protect her mental health. “I had to figure out what belongs to everybody and what just belongs to me.” She also turns to a network of peers for support. “I'm really fortunate that I have found a strong, vibrant community of Black women in kid lit who rally behind one another.”

Aside from blocking or calling out hateful reply guys on social media, authors tend to avoid confronting negative reviewers, even if it takes all the willpower in the world. “I'm very cognizant of author-reader boundaries, or power dynamics,” says Gong. Though she will clarify factually incorrect reviews with screenshots that block out the writers’ names. “I don't want anyone being attacked. The internet is messy.”

How messy the internet can be was put on display in April when Leaving Isn't The Hardest Thing author Lauren Hough tweeted screenshots from two four-star Goodreads reviews of her book and called the reviewers, "f*cking nerds on a power trip." (Lauren Hough's publicist did not respond to our request for comment.) Her tweets became part of a news cycle, which caused authors and reviewers to debate the power imbalances between authors and reviewers. Readers bombarded the book's Goodreads page with bad reviews, tanking the rating average, but still, the book became a New York Times bestseller.

The stress and confusion of navigating how and when to engage with online reviews may be why so many authors are itching to experience IRL connection with readers at book events, conferences, or festivals. For those of us who have never published a book outside the pandemic, face-to-face events seem like relics from another era — one where Amazon reviews weren’t the only kinds of interactions we had with readers.

In my wildest dreams, these events feature meaningful conversations with people who are interested in your work, where you can have nuanced interactions that don’t necessarily end in a starred rating system. They’re places where online trolls would never dare show their faces. Is that totally naive? Probably. And those moments would, of course, never make the online critiques authors face ever go away.

But Harris has had a few IRL events in recent months, and they’ve gone well. “Having in-person interactions with five people outweighs a lot of the negative stuff,” she says. “It’s a really big thing I didn't even realize I was missing until I had a couple in-person events. Having people look me in the eye and respond to my work, it was like, ‘Wow, this feels exactly what I thought it would feel like.’”