Books

How Horses Helped My Ancestors Evade Colonizers, & Helped Me Find Myself

Writer Braudie Blais-Billie grew up between two worlds. Horses allowed her to bridge the gap.

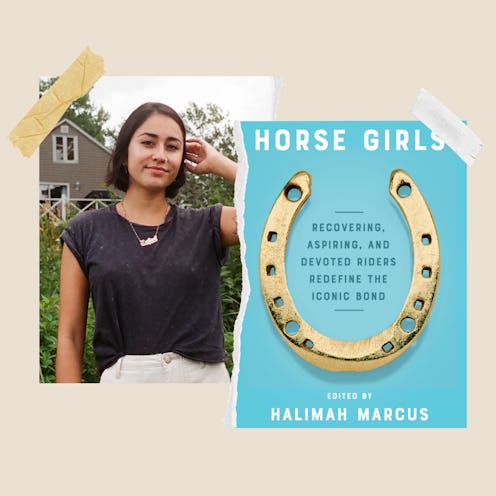

In this essay excerpted from Horse Girls, edited by Halimah Marcus, writer Braudie Blais-Billie reflects on how horses shaped her family history — and her understanding of herself.

Growing up on the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Hollywood Reservation, everyone called us “the Frenchies.” This was because, since I was around eight years old, my mother — a French-Canadian woman conspicuously named France — raised me and my two younger siblings as a single parent on the Rez. Blond-haired and blue-eyed, she stood out at every basketball game and community holiday dinner. “That’s your mom?” my neighbor asked when she picked me up from an after-school playdate down the street. “I look more like my dad,” I offered. It was true. My father and I had the same almond-shaped eyes and sleek brunette ponytail hanging down our backs. Reserved yet mischievous, he oscillated between cracking jokes and reading World War II books in his room; from him, I inherited my quiet, curious nature.

Most times, “the Frenchies” felt like a warm recognition. Our ekòoshes cooed the nickname with love when we walked through their doors for birthday cakes or sleepovers with the cousins. Other times, it hung in the air like something rotten. When used by certain people on the Rez, “the Frenchies” was a sharp-edged epithet that meant “not like us.” It also complemented the less creative nickname we heard in Canada whenever we visited my mother’s Québécois family: “les Indiens.” As I got older, each label became more uneasy for different reasons.

My siblings, Tia and Dante, and I were born without a Clan. A traditional extended family unit, Clans are matrilineal, meaning that because our mom is white, we’ll never have one. It meant that “the Frenchies” were not invited to partake in ceremonial medicine like the Green Corn Dance, that we were always considered “half,” that we were not wholly welcomed in the place we call home. Because our Seminole father, July, was absent from our childhoods, his mother — our empóshe, Grandma Hannah — would visit on weekends to feed us candy and teach us the culture that France couldn’t and July didn’t. “We’re unconquered people,” Grandma Hannah said.

Like my mom, she stood around five feet tall, and she was commanding despite her soft-spokenness and salt-and-pepper hair. On the days Grandma Hannah picked me up from my Head Start preschool program, she told the legend of our ancestor, Chief Osceola. Osceola was a warrior who led Seminole resistance forces against the US military in the nineteenth century. He famously drove a dagger through the 1832 Treaty of Payne’s Landing, refusing to concede the Tribe’s Florida lands in exchange for “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi. It was a heroic, radical act that quite literally made it possible for us to be here today, thriving in Florida. Through her eyes, I saw our little neighborhood of brown relatives and cookie-cutter homes built by the government’s Department of Housing and Urban Development as a blessing.

It was Grandma Hannah who brought me to my first rodeo. From an early age, I passively absorbed rodeo culture as an integral part of Rez culture; it was evident in the rusty horse trailers parked in neighbors’ driveways and the Tribal Councilmen who donned cowboy hats and Western boots at every public event.

As an adult, years after Grandma Hannah’s introduction, I learned that the connection between my people and horses comes from a long line of cattle keeping. Before moving into gaming in the 1970s — both my dad and Grandma Hannah worked stints at the Seminole Classic Casino — the Seminole Tribe of Florida provided for our people through enterprises including citrus groves, tourism, tobacco shops, and, most prominently, cattle. Over the past century, the Tribe has risen as a major player in the cattle industry. Seminole Pride, the Tribe’s beef brand, is a sizable contributor to Florida’s beef cattle herd — the tenth largest in the nation, according to a 2016 report by the US Department of Agriculture. When I drive through any of the more rural Seminole reservations — like the winding fourteen-mile Snake Road that cuts through the Everglades to the Big Cypress Rez — I see horses and cattle dot the swampy pastures.

As a child, I wandered the rodeo grounds sweating through the South Floridian heat in my traditional patchwork skirt. I watched in awe as Tribal members competed in events like barrel racing, bronc riding, and “stray gathering,” in which a team on horseback captured runaway calves with lassos. “One day you’ll be down there,” Grandma Hannah declared as we sat in the bleachers chewing warm frybread and sipping cold ponche, the Mikasuki word for “soda” that I thought was universal until I started going to my white friends’ houses. She noticed my ease around horses, that counterintuitive confidence required to handle a potentially lethal animal. My mom had been taking me to riding lessons since I was six, where I was encouraged to lead the ponies myself and stay attuned to their body language. Up in the bleachers, I held my breath as steeds swiveled around barrels, running against the clock, exhilarated by the possibility that it could be me whipping through the loose dirt of that arena. At the rodeo, I wasn’t just a “Frenchie”; I could be another rider.

My parents separated when I was in third grade. My dad’s alcohol abuse — an illness that cycled, destructive and dormant, throughout my parents’ marriage — had reached the point of unmanageable. “Daddy’s going to live somewhere else from now on,” my mom told me as I stood by the front door. She crouched down to meet my eyes and rubbed my back as Tia and Dante wailed on the couch. When the school year ended, my mom packed us up and we spent the entire summer at my grandparent’s house in Québec, Canada. My dad didn’t come.

That was the year I started riding at a new show jumping barn called Fox Run Ranch in Davie, a few towns over from the Hollywood Rez. My mom rode English, so I wanted to ride English, and once I discovered you could jump a horse, I wanted to do that more than anything; it seemed unreal, like the closest thing to flying. Though the Rez had its own stables, they didn’t give English-style lessons, and there were no English categories like hunting or dressage at the Seminole rodeos. As Grandma Hannah realized I wouldn’t be barrel racing, our rodeo outings became less regular until she eventually stopped bringing me at all.

Though he was never consistently in my life, my dad’s absence from our home was a palpable sore made raw over and over again by Grandma Hannah’s dwindling visits and the prying questions from neighbors and classmates. The specifics of this period are a painful blur, an amnesia that, when revisited, allows only feelings of loneliness, immense anxiety, and sadness. A hardening resentment toward my dad took root; I was too young to understand the complexities of his illness and instead interpreted his drinking as a betrayal. How could he do this to me? Soon enough, I realized that when I was on a horse, synced to its gait in the arena, my grief became so distant I barely recognized it.

Summers in rural Québec, far away from the humid stench of Hollywood and the fighting between my parents, were an escape into a simpler world. My mom’s parents, Grandmaman Jeanine and Grandpapa Gabriel, lived in a trailer-turned-house on 2.5 acres that seemed to extend infinitely into the woods and dirt roads of the surrounding farmland. It was located in a small town called Saint-Isidore, a cool forty-minute drive outside of Québec City. We called it the Canada house.

I can close my eyes and still see every inch of the Canada house and its property. The front porch overlooked a small, man-made pond and waterfall that Grandmaman decorated with flowers and stones collected from the Chaudière River a few miles west. The yard was a cluster of evergreens and birch trees, some with branches swollen around the rope of multiple swings that Grandpapa fastened with sturdy chunks of wood as seats. Behind the house, a stretch of wooden fence contained a pasture of rolling grass and dirt. To the right side of the house, there was a small barn painted white and green. Throughout its days, that barn housed chickens, rabbits, mini goats, and horses.

Despite their years of owning and managing motels in South Florida, neither Grandmaman nor Grandpapa spoke fluent English. This was due in part to the nature of their business, which consisted entirely of Québécois snowbirds, who escaped the harsh winters of Canada en masse to the beaches of Hollywood, Dania Beach, and Fort Lauderdale. Though French was my first language, my mother spoke to me exclusively in English once I started pre-K, and my proficiency never really evolved past that of a child. Simple phrases like “je voudrais” and “est-ce que je peaux” carried my siblings and me through most interactions with our grandparents, which revolved around daily activities like family meals, watching TV, and, most importantly, Grandpapa’s horses.

He owned three. There were two retired racing Quarter Horses, the well-behaved Storm and the sweet but sometimes mischievous La Fille Fille. Their sleek, brown coats and elongated features distinguished them as the twin beauties of the barn. But it was Petit Prince, a stocky, temperamental pony with an unruly black mane, who was the star of the show. He was almost half the size of Storm and La Fille Fille, but he was staunchly the alpha. One of Petit Prince’s favorite power moves was pushing the poor Quarter Horses aside with bites and kicks to the rear whenever sugary treats were within reach.

Storm, La Fille Fille, and Petit Prince were always Grandpapa’s favorite pets, always his most prized. He grew up poor in a small Québécois village where he worked odd jobs and rode local unbroken horses for fun. Horses were a luxury, unobtainable despite his love for them. After years of manual labor and driving semitrucks, he was able to start his own business and move to the States. In his retirement, decades after he first fell in love with horses, he was finally able to possess his own.

The annual summer Blais family reunion was highly anticipated, yet complicated. Much like at gatherings on my Seminole side, I was constantly being introduced to a handful of new cousins I’d somehow never met before. But even more so than on the Rez, my siblings and I were undoubtedly the outsiders. Well-meaning family members would compliment our thick, dark “indien” hair, our “chinois” eyes, how brown our shoulders and cheeks turned in the sun. Once, I overheard an aunt explain to another that the reason I was able to run through the birches barefooted was because of my Seminole blood. Laughing about it was my best defense against the discomfort. The second-best defense was trying not to think about my Nativeness, drawing as little attention to that part of myself as possible. I knew that these people cared for and loved me deeply — that’s what made it so hard to identify the wound that their casual othering left behind. But the unpleasantness dissolved when the evening wound down and my favorite part began: the Petit Prince–drawn carriage. After dinner, Grandpapa would disappear into the barn and, around fifteen minutes later, Petit Prince emerged from its garage door, clacking his hooves on the gravel and towing outstretched palms and incessant clucking. Every juicy handful of grass and wildflowers, and every apple yanked from the yard’s apple tree, became an offering to our four-legged best friends.

When I was seven, my mom sent me to horse camp in Breakeyville, a small town fifteen minutes north of the Canada house. There, I was the only English speaker and the only nonwhite person amongst the ten or so campers. It was similar to my experience at the barn I rode at in South Florida, where most of my peers were also white. But in Québec, I grew as a rider. As a kid who was painfully self-conscious of my shitty French accent and what I learned were my obvious “indien” features, the only person I really interacted with was my favorite instructor, Marie.

One morning, Marie and I spent hours in a one-on-one lesson because I was the only advanced camper who showed up that day. Determined to impress her, I repeated her show jumping exercises over and over again, sweating into my helmet as she raised the poles, my horse flying higher and higher at my command. When I inevitably had my first major fall and ripped a hole in the crotch of my jeans, we just laughed. “It happen to all of us,” she assured me with her thick French Canadian accent and toothy smile. Later, eating limp ham-and-cheese sandwiches with everyone in the tack-turned-lunchroom, I wasn’t even embarrassed by my visible underwear; I was proud to have something to show for my dedication.

Marie made me a better rider, but Davie’s Fox Run Ranch back in Florida was where I was introduced to a wider equestrian world. Sprawling and slightly run-down, the land sprouted with green overgrowth while white, chalky sand paved the trails and pens. My siblings and I spent most of our time in the covered, rodeo-size arena where we took group lessons and, during horse camp, painted our ponies’ hides with horse-safe glitter and bobbed for apples. Inside jokes were formed with other eager campers and dream ponies were discussed as we groomed our assigned steers from the stable. In Davie, the Blais-Billies weren’t unintelligible foreigners — like at school, we were once again those Seminole kids from Hollywood, familiar but still other.

At shows, there was occasionally another rider of color from another barn. Still, I couldn’t ignore the chronic suspicion that I didn’t belong or deserve to be there. I was competing against girls with purebreds, shiny new saddles, and pristine uniforms — their wealth rolled off their shoulders in the form of innate self-assurance. Even at our barn, I found myself dodging questions from white riders like, “Which neighborhood do you live in?” or, “What does your dad do?” I was never in the mood to explain what a reservation was or that my dad was an alcoholic who disappeared on benders for weeks at a time. We shared a bond over horses, but we never became close. Distance was my friend when it came to protecting myself from shame or rejection.

My priorities shifted at the Canada house as I got older. The year I turned ten, I was expected to help Grandpapa mornings and evenings in the barn, raking the horses’ stalls clean and refilling their buckets with cold, metallic well water from the hose. Well into the last year of his life, Grandpapa was as strong and active as someone in his thirties — he single-handedly cared for the animals, chopped firewood for the furnace, and fixed things constantly around the house. On top of our language barrier, he was a man of few words who was hard of hearing, so our barn chores were completed mostly in silence. But talking wasn’t necessary; we were doing what needed to be done, hoisting forklifts of hay to hungry muzzles, helping one another take care of the beloved creatures that occupied our days.

It was around this time that my mom allowed me to ride La Fille Fille, who became stubborn and uninterested with a saddle on her back. We took turns warming her up on the lead and then willed her into canter drills around the pasture while Storm and Petit Prince munched on carrots in their stalls. With the increasing chaos of our family life back on the Rez — my parents’ separation only seemed to exacerbate my dad’s drinking as the years went on — I cherished the semblance of structure and responsibility dictated by the parameters of my quiet, Québécois farm life.

Grandma Hannah likes to joke that my Mikasuki name, Lokaeechete — which roughly translates to “something passing by in the distance” — is a self-fulfilling prophecy. When I graduated from college in Manhattan, I stayed in New York City, opting for the less hectic borough of Brooklyn. Today, I’m still in the same sleepy Brooklyn neighborhood, piecing together my own life far away from the Hollywood Rez. I fly back for holidays, but extended stays are a confusing mixture of triggering and healing. This became especially true when my dad lost his battle with addiction in 2013.

Recently, Dante moved back to the Rez after their college graduation. We talk on the phone often; they’ve become my closest connection to the place that, for better or for worse, will always be my home. So it’s on an unremarkable spring afternoon when Dante calls to tell me about our paternal great-grandfather, Harjo Osceola.

Though we grew up on the Rez, my siblings and I had never heard of Harjo Osceola. We knew about his son, Genesis Osceola, our father’s father, but even that knowledge was severely limited. Genesis was absent from my dad’s life completely; we never got to meet him before he died.

Since our own dad passed, we’ve begun the project of reanimating the life he never really shared with us. We cling to every shred of information gleaned through family stories, social media, or Rez gossip. We compare notes, carefully weaving facts and feelings together to fill in the blanks left behind by generational trauma and decades of communication breakdowns. Dante’s phone call is energized with the air of potential, a chance to understand who our dad was as a Seminole man, who we are as Seminole people.

“Apparently, he was a prominent Seminole cattleman,” Dante says. They text me a black-and-white photo from what looks like a history book and explain that their colleague, another Tribal member, sent it to them when she found out who our father was. I zoom in on the photo, a group portrait of seven Seminole men from the 1950s. They sport baggy button-up shirts tucked into heavy denim and lean against a tall wooden fence surrounded by the twisted branches of Florida’s live oak trees. They all wear cowboy hats and grip cattle-branding irons. My Harjo’s eyes are cast down, his cheekbones small but sharp, his iron spelling “HO.”

I wonder if my dad knew his grandfather was a Seminole cattleman, if that would have made things different between us. Would he, instead of Grandma Hannah, have taken me to the rodeo? Would he have found pride in who he was, giving him the bravery to fight a little harder to stay around? From what I’ve heard, all it took was one scary fall as a kid in Big Cypress for him to write off horseback riding forever. It strikes me that most of my friends in Brooklyn have no idea that I ever rode. I consult the group Instagram DM I have with my siblings: “You guys ever contend with the fact that we were horse girls?”

Tia — a classic middle child keeping the peace with something witty at hand — answers immediately: “I talk about it nonstop.” I laugh, because it’s kind of true. When the three of us are together, we’re always bringing up our memories of horse camp, of Petit Prince. It astonishes me that I never associated these facts with the broader consciousness of the pervasive “horse girl” memes and stereotypes. “I buried it so deeply in my subconscious,” I type, “but I’m finally excavating.”

Sure, I was the weird girl in middle school who kept to herself, read horse-themed YA, and sketched wild stallions on ruled paper. But I wasn’t a horse girl — I couldn’t be. I wasn’t a white, rich femme like the Clique’s Massie Block or the girls I competed against from places like West Palm Beach and Boca Raton. I couldn’t relate to the privilege or sheltered existence that people around me projected onto the young women who openly loved horses.

Even within the barely-there mainstream representation of Native Americans in movies and TV shows, I wasn’t the type of Native that non-Natives associated with riding. At my elementary school, where I was the only Indigenous student in my grade, classmates would come up to me during recess and ask me if I lived in a teepee, if I had electricity, if I rode a horse to school. “Um, we have a car,” I would scoff back to hide the water rimming my eyes. I vividly remember the burn of my face when a kid told me my dad was stupid because he was an Indian who “danced around a fire.”

I saw that for my peers, “Native American” evoked only imagery they were familiar with: Plains Indians, like the Lakota and Blackfoot, frozen in the nineteenth century. To them, I was buckskin, headdresses, and Appaloosas with war paint. That’s just not what my family looked like. Our history classes also taught them that Natives were dangerous “savages” who were vanquished by our forefathers because they were intellectually inferior. We learned that the first “American Dream” was “Manifest Destiny,” the delusion, veiled as divine purpose, that Christian settlers were destined by God to expand across the New World. I’ve lost count of how many times children and adults alike have said, “I didn’t know you still existed” to my face. Off the Rez, I was either invisible or an uncivilized relic on horseback.

By the time I started high school, my parents had been separated for around seven years, and my dad’s drinking was at its worst. He became a ghost of the person I loved, so I rejected him and the parts of myself that were him, alchemizing my broken heart into anger and self-hate. I wanted to be all Frenchie and no Indien. I wanted so desperately to be like everyone else at the small, predominantly white private school I transferred to and attended on a scholarship. I wanted to be thought of as “normal,” and maybe, one day, even cool.

I quickly surmised that horseback riding would not help my case — not as the only Native American in the class, and most definitely not as a socially awkward newcomer who still shared a bedroom with their sibling because our HUD house was so small. I went from daily lessons to biweekly to none at all; competitions became a thing of the past. I felt guilt when Grandpapa asked me about riding once I’d stopped. But who could blame me for abandoning a world that never fully welcomed me to begin with?

What I’ve been taught since I can remember and what I know is true: the Seminole Tribe of Florida never signed a peace treaty, never surrendered our land or our people to the United States. In college, studying the nuanced Indigenous history I wasn’t exposed to in the Florida education system changed my life. It gifted me with the vocabulary to unpack my experiences as an Indigenous woman and a space for me to contextualize the pain my dad experienced as an Indigenous man, how he coped with what was available to him. In his death, I forgave him, accepted him, and began to accept myself, too.

But when I follow the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s history with cattle and horses, our unconquered resilience goes back even further than I imagined. According to leading Seminole historian and anthropologist Patricia Riles Wickman, the mastery of cattle herding and horseback riding defines the Tribe’s relationship with colonization. It was the ancestors of the Seminole people — the precontact tribes of what is now known as Florida — that were some of the first Indigenous nations to husband these animals.

In the late 1500s, Spaniards established the first permanent European settlements in what they called “La Florida.” The land was occupied by many different societies, including the Maskókî, Hitchiti, Calusa, Yamásî, Chicása, Apalachi, and Timucua tribes. As foreign invaders, the Spaniards’ dealings with the original peoples were an ever-evolving hybrid of violence and diplomacy, depending on what they needed.

Much like the rest of colonial history, the Spanish established mission villages to “save” the Indigenous peoples’ souls and assimilate them to Western ideals of civilization through the vehicle of religion. (Because of this, my dad instilled in us a healthy dosage of skepticism when it came to Christianity; I still reflexively cringe at the mention of Jesus.)

The Spanish also incentivized the Natives to work cattle “ranchos” with land grants, which, of course, consisted of land the settlers had previously stolen from said Natives. With a plot of land and some livestock, the Natives worked raising and selling animals back to the Spaniards at whatever price they were willing to pay. This is how they exploited Indigenous labor for profit. By the late 1600s, the Maskókî people established high-profiting cattle herds in what’s become today’s Alachua savannah in Micanopy, Florida; this prairie is where the group that became known as the Seminole people began.

Throughout the five hundred years of violent colonization and systematic genocide, the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (North America) always rebelled. In La Florida, many were subjugated, but many also fought and escaped, finding refuge around the Alachua savannah cattle rancho. There, peoples from various tribes across the occupied land were able to find work and thrive outside of Spanish, then British, and then US control. Natives from territories neighboring Florida, as well as escaped African slaves, were also moving south in search of freedom.

Using the term their countrymen coined to describe escaped slaves in the Caribbean, the Spaniards called this growing, diverse community of rebels “cimarrones,” which meant “wild ones” or “runaways.” After decades of playing telephone through multiple Indigenous and European languages alike, “cimarrones” became “Siminolie” and then eventually, “Seminole.”

It’s satisfying to see how poorly the Spaniards’ master plan played out; I smile to myself knowing that my ancestors one-upped their oppressors. When the Maskókî and Apalachi and Timucua and Calusa and Hitchiti and Yamásî and Chicása people were forced into labor, they adapted. They learned the ins and outs of ranching, applying thousands of years’ worth of knowledge about the land to the craft of keeping herds alive as the runaway Seminole peoples. They studied the economic customs of the settlers, becoming acute businessmen for the survival of their communities in an ongoing war.

Even hundreds of years later, during the bloodiest years of Seminole resistance against the US, the skillful husbandry of scrub cattle and horses kept the remaining few hundred rebels fed and alive. The Seminole Wars, three in total, spanned from 1817 to 1858 in a concentrated effort to eradicate the “Indian problem” of Florida. Initiated by the notoriously belligerent Andrew Jackson, the series of concentrated military efforts failed to completely remove the Seminole people every single time. During the Second Seminole War alone, the US spent almost $40 million to try to capture and relocate around 3,000 men, women, and children to Oklahoma, or “Indian Territory.” It was also the only Indian war in American history that employed the army, navy, and marine corps — unsuccessfully, I might add.

I find Harjo Osceola listed in the United States Federal Census for Hendry County, Florida, on Ancestry.com. The document states he was born in 1913 and died in 1978 at age sixty-five. He lived twenty-six years longer than my dad.

In a 1972 interview with the University of Florida’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, Harjo’s younger brother, Reverend Billy Osceola, detailed the family’s life in the early days of the Seminole Brighton Reservation near Lake Okeechobee. “That time, we [didn’t] have any reservation,” he stated. Harjo, Billy, and their siblings harvested their father’s vegetables down in Big Cypress to feed themselves. They hunted alligators, raccoons, and otters, selling their hides and meats to white traders in Indiantown. Their mother, Nancy Osceola, passed away when they were just teenagers.

They spoke English and Muskogee, or Creek, which is one of the main languages Seminole Indians still speak today. My dad spoke Mikasuki because for a good portion of his childhood he was raised by his maternal grandmother, who didn’t speak a word of English. Grandma Hannah attempted to teach me some words; sadly, I can count the amount of things I know how to say on one hand.

Googling “Seminole cowboys” in my Brooklyn apartment, I try to envision Harjo in the tanned faces of Tribal men staring indifferently toward the camera on their steeds. By 1957, when Harjo wrangled the fields, the Seminole Tribe of Florida became a federally recognized tribe. That meant the Brighton Reservation was officially an agricultural and livestock enterprise independent of the US government. The Tribe was able to appoint their own land trustees internally, eventually using that legal foundation for future land claims and reparations. I write this down, feverishly, in anticipation of telling Dante that our relative’s work was crucial to the political advancement of our Tribe. Our great-grandpa!

Researching Harjo reminds me of one sticky night on the Rez. I had just moved to Brooklyn and I was home decompressing for a week. It had been three years since my dad died, and Grandma Hannah made a habit of coming over with her tóhche, who we called Uncle Paul, to tell us stories in the backyard while the sun sunk behind the freeway. Mosquitos pricked our backs and cicadas whirred, but Tia, Dante, and I listened attentively. Uncle Paul spoke about the way-back-when times of the Seminole Wars, detailing the lore and lessons our people bore in hopes of one day telling their great-grandchildren. I eyed the darkening skyline, my heart swelling tight at the image of my ancestors slithering into empty alligator burrows to evade US troops. “They knew the land like no white man did,” he said.

Tia and I have settled on the loose term “Seminole horse girl.” It seems simple, but the specificity allows just enough space for the intricacies of our biracial identity. Like the Seminole peoples, “Seminole horse girls” originates from a conglomeration of cultures adapting to their environment; sometimes not belonging to one group exclusively can be empowering. I’ve found that, in our family, horseback riding is more than show titles and prestigious stables — horses are how we survive.

For so long, horses were the love language that kept me tethered to the peace and stability my grandparents offered by way of sharing their home every summer. The Canada house was a place where I was safe to explore, process, and build the confidence I wasn’t able to in the noise and identity politics of South Florida. All those years of horseback-riding lessons, horse camp seasons, new riding boots and tack — those were reassurances from my mom that we were just as good as the snooty kids at competitions, that we’d have fun and meaningful lives, no matter how unstable our household.

A few months after my dad died, Grandpapa passed away from cancer. The year before, in 2012, he had to put down Petit Prince due to an incurable abscess in his mouth that caused him to stop eating; Storm had already succumbed to lung disease a couple years before that. Seeing Petit Prince’s death as a sign, Grandpapa sold his remaining horse, La Fille Fille, to “une gentille vieille dame” who lived not too far from Saint-Isidore. It was a hard decision, but he visited her a couple of times in her new home. She seemed happy. Less than eight months after Grandpapa’s passing, we said goodbye to Grandmaman, too.

I think about my Seminole ancestors every day, like I think about my dad and my grandpapa and my grandmaman. So much was lost, and yet, I am here now. I give thanks for what they’ve done and who they were. I want to stop strangers on the street, grab their shoulders and shake them and scream, “Do you know what they meant to me and to my understanding of myself?!” Though my Seminole and French-Canadian sides feel like worlds apart, they each gifted me with a reverence for horses that bridges the distance that once overwhelmed me. I follow the bloodline down and I see who I am: July, Genesis and Grandma Hannah, Harjo; France, Grandmaman, Grandpapa. I ride bareback in a sunny Canadian field and wonder, if Harjo could see forward, would he see me? Certainly this equestrian dynasty, this way of living that connects me to all my loved ones, could warrant such foresight.

“Unconquered” Copyright © 2021 by Braudie Blais-Billie. Excerpted from HORSE GIRLS. Copyright © 2021 by Halimah Marcus. Reprinted here with permission from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This article was originally published on