28

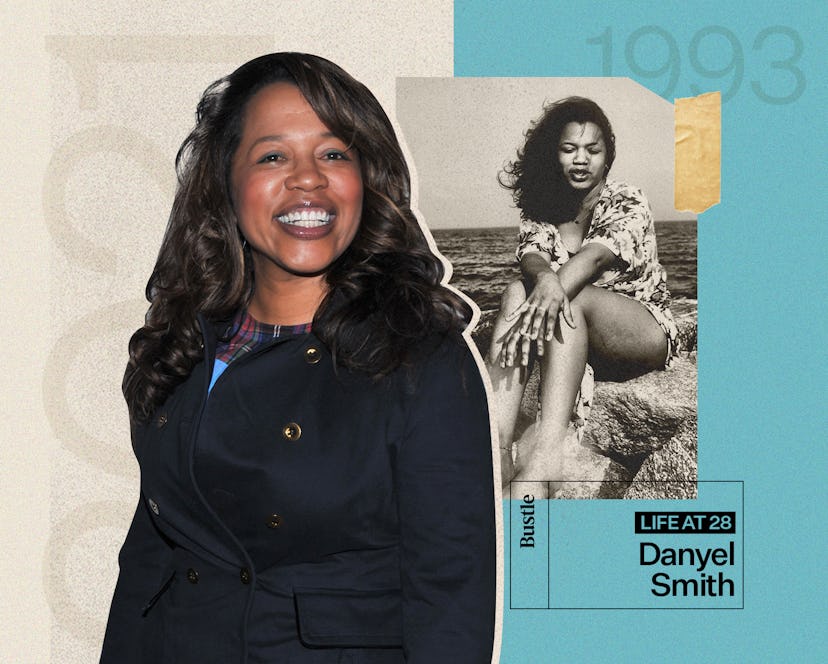

At 28, Legendary Music Writer Danyel Smith Learned From Leaving

“I had no problem telling Whitney Houston that I was recently divorced.”

Since her early days as a journalist, Danyel Smith has made it her career mission to put Black music front-and-center in mainstream media. She made her mark with intimate interviews with the world’s biggest stars — Beyoncé, Wesley Snipes, and Simone Biles — the secret to which is Smith candor.

“I had no problem telling Whitney Houston that I was recently divorced and that, at that time, I was still harboring some desire to get back together with my husband,” Smith says. “I talked to her about that. And that allowed her to speak to me frankly about her relationship with Bobby Brown.” A conversation with Danyel Smith is like this. When it comes to the conversations she’s had with many of her A-list interviewees, she says, “[The publicist] told me I had an hour. Please — you know I got four.”

After stints writing and editing for Spin, The New York Times, and Billboard, Smith became the editor-in-chief of Vibe — the first woman and first African American to do so. She then went on to write two novels while continuing her crusade to tell underrepresented stories everywhere from Time to ELLE to ESPN. Her new Spotify radio show, Black Girl Songbook, brings her three decades on the scene to pivotal moments in music history that have defined generations, like Whitney Houston’s iconic rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Smith's forthcoming book of memoirs and music criticism, Shine Bright: A Personal History of Black Women in Pop (September 2021, Roc Lit 101), blends her critical and literary talents.

But at 28, Smith was just getting started. She’d just gotten married, landed her dream job, and was seeing the world anew. Gangsta rap was blowing up across the country. The industry wasn’t welcoming to the new sound, but she wasn’t hearing that. “All I wanted to do was dance to Snoop and everybody else.” She estimates she’s seen about 2,000 music shows in her lifetime, and at the height of her time as a music writer attended at least two a week for fun, plus three on assignment.

If we go back to when you were 28, what do you see?

1992 was a real transitional year for me. I'm from Oakland and moved to New York to be the R&B editor of Billboard, which was just the literal dream of my life. I had been working hard in Oakland to make a name for myself as a music critic and cultural reporter. I received a call from a guy named Bill Adler, the then-publicist for Run DMC whom I'd worked with on some stuff. He had recommended me for the R&B editor position, and Billboard flew me out for the interview — again, one of those things that I could not have dreamed of back then. However, I thought that I did an absolutely terrible job at the interview — I had on an ill-fitting suit that I'm sure cost me like $19.99 at MacArthur/Broadway mall in Oakland — but I got the job.

Was it smooth sailing from there?

Well, I was a newlywed. I'm a writer, and I married a photographer. I thought I had this amazing marriage, and it was for the first year or two. We would cover shows together, I felt in this amazing creative space. But sometimes you get into situations where one person starts moving at a different speed than another, and if you don't have the tools to navigate those differences it can lead down a bad path.

"It was a crazy year, but I got some of the best work of my lifetime done — work that set me up for the rest of my career."

I ended up staying in my job only for I think, seven or eight months. I remember thinking it would help my marriage if I went back to freelancing. But also, hip-hop was blowing up so big at the time, and the culture wasn't as it is now. The music industry wasn't welcoming to rap, especially not gangsta rap. Gangsta rap was so divisive at the time. I’m not saying it doesn’t have its problems — it’s probably one of the more problematic parts of hip-hop. But you couldn’t tell me that at 28. I wanted to help my marriage, and I also wanted more freedom to write the things I wanted to write about. So, right after those eight months at Billboard, I started freelancing “like a bat out of hell,” to steal a phrase from my grandmother. I was writing for whomever or whatever called. It was fantastic. I went on the road with Cypress Hill for Rolling Stone, but I reviewed Neil Diamond, Harry Belafonte, Johnny Mathis, and Tina Turner albums and concerts for the New York Times. It was wild too because, at 28, I’d sit there and think, How am I doing this?

But sometimes doing incredible things on your own doesn’t make for [a] very jamming home life. I signed the [divorce] papers at 30, but I was separated by the start of 29. That’s why I say 28 was a transitional year. It was a crazy year, but I got some of the best work of my lifetime done — work that set me up for the rest of my career.

At the time, people were like, “Your career is going to be messed up. You left Billboard after only eight months; it’s going to be bad for your record,” but all the things that I did in ’92 got me the music editor position at Vibe magazine, which led to me becoming the EIC.

I love Billboard, and they ended up having me back as editor many years later.

What do you think your 28-year-old self would think of the woman you’ve become?

She would say, “Cool. What's next?” That girl has things to do, places to go, and people to see. And whatever I'm doing right now she would think is fantastic. But she would wonder, “So what's the plan? You wrote the book?” “Finally,” she would say, “I see you got your little podcast going. Super cute. But where's your documentary? Where's your second book? What girls are you helping right now become who they want to be?” So, she would be like, “You're kicking it right now, but you need to get back to work.” I don't know why I'm like that. Looking at my future, I see peace and relaxation, but I will always push myself to make more stuff.

This article was originally published on