Books

How My Chemical Romance Inspired Dana Schwartz’s Latest Novel

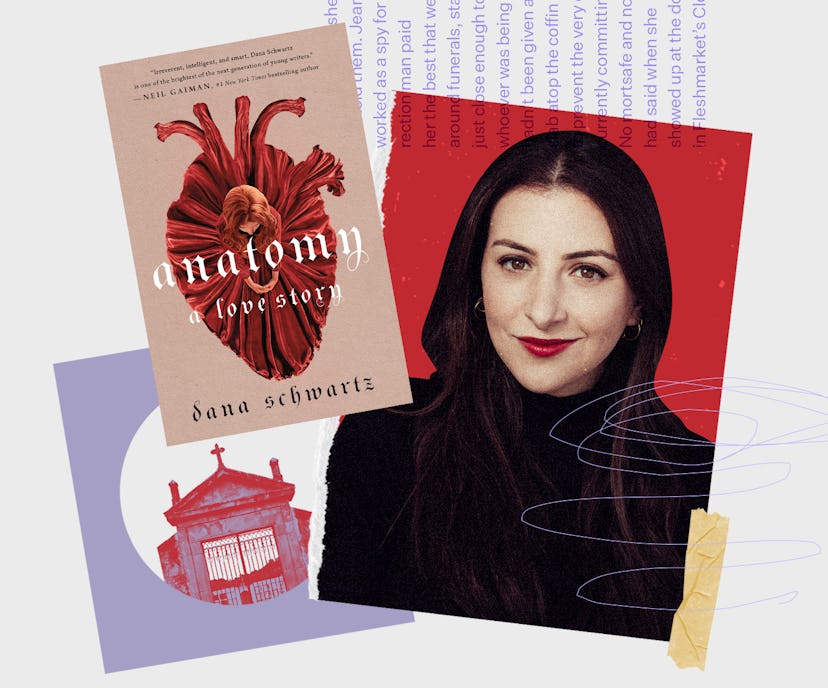

Anatomy: A Love Story follows two teens who strike up an alliance in the unlikeliest of places: the graveyards of 19th century Scotland.

The Martian Chronicles. Ender's Game. Oryx and Crake. These were the genre-leaning, heavy-on-the-adventure types of books that shaped novelist (and Bustle columnist) Dana Schwartz in her youth. “I grew up loving authors who are able to tell very grounded human stories in fantastical worlds,” she tells Bustle. “I also loved The Handmaid's Tale. Margaret Atwood is really good at spanning that chasm between literary fiction and genre.”

Schwartz first cut her teeth with a series of humorous books. The comedic memoir, Choose Your Own Disaster; the satirical White Man's Guide to White Male Writers of the Western Canon. But now she’s publishing her first entry into the canon of genre fiction, an homage to the mysterious and macabre tales that enchanted Schwartz throughout her adolescence. “My impulse as a writer is just to do what I'm most excited about,” she says. “Because the thing about writing a book is you have to spend a very long time in this world with every character.”

The result is Anatomy: A Love Story, which centers on two teenagers in 19th century Scotland: Hazel (a would-be surgeon) and Jack (a body snatcher). Together they solve mysteries, exhume corpses, and, of course, dabble in romance. And the novel, which was released this week, has already been selected to be part of Reese Witherspoon’s book club. Explaining her choice Witherspoon wrote, “I think you’ll really enjoy the secrets that begin to unravel, and spooky adventures riddled throughout this historical fiction.” The exact kind of pitch that would’ve enticed a young Schwartz to pick up a book, all those years ago.

You’ve said being a Tumblr-loving, My Chemical Romance-listening teen partially inspired this book. How did your emo girl origins manifest into Anatomy: A Love Story?

I was a very good suburban girl. I was a straight-A student, president of the debate team, math team — everything parents would want in a suburban child. But I did have that element of myself where I thought liking My Chemical Romance was rebellious. I always gravitated towards theatrical emo music. I like things with context and story. I love concept albums. Now, in retrospect, there's sort of an earnestness that I was attracted to. Even loving something as a teenager, there's an earnestness to that. So [in this book] I was trying to capture that feeling of being 16, 17 and everything feeling like the weight of the world.

It was kind of scary for me to write this book because so much of my writing online and my online persona has an element of detachment to it. I’m usually a little snarky or sarcastic. But you can't be sarcastic while writing a love story about teenagers solving mysteries in 19th century Scotland.

The internet isn’t exactly a breeding ground for earnestness. What intimidated you most about allowing yourself to go there?

Writing a Gothic, medical love story set in the graveyards around Scotland was an idea that I really loved. So the scariest part was hoping that I would be able to do justice to the idea in my head. It was like, “Am I a good enough writer? Am I disciplined enough?” I feel like such a fraud for even saying this but it’s like, “I'm very insecure and I tried really hard on this!” So that’s scary.

Your work is so chameleonic. You write pop culture commentary for Bustle, have a podcast about nobility, and are now putting out this YA historical fiction novel. Have you ever been pressured to stay in your lane?

I probably could have had a more successful career quicker if I could find a niche for myself and really commit to that niche. But the problem is I'm genuinely interested in all these things. I really love historical fiction. I remember when I was telling people about my podcast Noble Blood — which is scripted and not particularly funny — people were like, “Are you making fun of it?” I'm like, “No, I just like history.” So I think my guiding principle has been following my genuine interest.

There’s also a lot of societal pressure on writers to pursue literary fiction. To be “the next Sally Rooney.” But you have such a passion for genre writing. How did you cultivate that?

I started the Twitter account [@guyinyourmfa] my senior in college because I was really intimidated by the pretensions of the 22-year-old fiction writers [in my classes]. I didn't think I was well-read enough, smart enough, or good enough to be swirling Chardonnay and talking about Jonathan Franzen with them. So I feel like I sort of channeled that insecurity into jokes. I also had a fiction professor in college tell me that he could see me one day being a very successful commercial [fiction] writer, which he meant as an insult, but it’s not.

It also goes back to wanting to write the things that I love. I started Noble Blood because I love spooky, macabre history. That's just like a thing that I could talk about for hours, so now I do it into a microphone.

Between Noble Blood and Anatomy: A Love Story, you’re doing a ton of research. How do you toggle between the two projects and, in turn, how have they informed one another?

Thanks to Noble Blood, I have spent a lot of time in the 1800s. And my lead character [in Anatomy], Hazel, isn’t titled herself, but she's still very connected to that world. Even though the book is heavily fictionalized — like the titles that her cousin has aren't real because they're characters — I tried to give it the veneer of truth. It's all based in fact.

For Anatomy, I also had to learn a lot about early surgery. I have a bookshelf of history of surgery books — and several books with very disgusting illustrations that I would never have out when company comes over.

What’s the strangest rabbit hole you went down in your research process?

I learned a lot about a man named Ignaz Semmelweis, who was a doctor who delivered babies. He realized that women who were having children delivered were dying of what they called “childbed fever.” He said, “Hey, what if we wash our hands when we reach up into women to pull the baby out. I think that'll help?” He was so knocked and rejected by the medical community that he had a mental breakdown and died in an insane asylum.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.