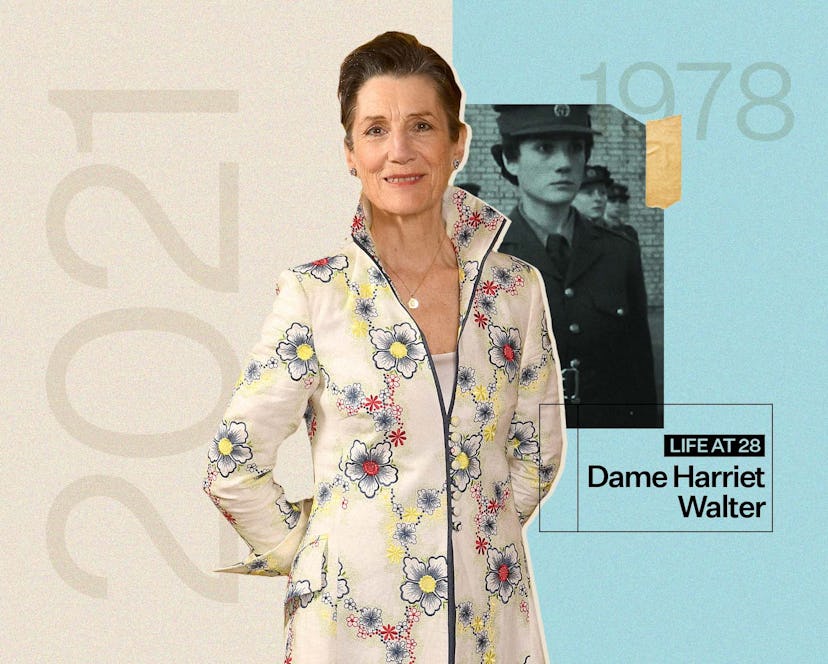

28

At 28, Dame Harriet Walter Was The Only Woman On Stage

Succession’s Lady Caroline talks beating anorexia, declining marriage proposals, and envying Meryl Streep.

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out, and what, if anything, they would do differently.

“It’s so deeply in my DNA that people who are judging me are male,” says British actor Dame Harriet Walter, who turned turned 28 in 1978. In her early career, she faced make-or-break reviews from theatre giants Frank Rich, Michael Billington, and Benedict Nightingale. Was that tough? “It was the norm,” she says over Zoom from New York, where she’s travelled for a wedding. “Authority was male. Judgment was male. If there were women, they were filtering male judgment. I accepted their criteria as the criteria, and now of course, Frank Rich is a cuddly producer on Succession. I can’t believe he was the Butcher of Broadway, but there you are.”

Her reviews were outstanding then — “galvanizing” (Rich), “impressive” (Nightingale), “remarkable” (Rich, again) — and still are, though she doesn’t read them with as much weight. “It’s very different [now],” she says. “There’s a diaspora, into social media, into blogs. Anybody can say anything, and it’s almost too exhausting to get the feedback.” At 71 years old, Walter has earned the right to ignore them. Her theatre work is legend — she’s won an Olivier and been nominated for a Tony — but those of a younger generation will probably recognise her as Dasha from Killing Eve, or Rebecca’s mother in Ted Lasso, or Lady Caroline from Succession, even if these roles were the easy ones. “I’d love to do something very complex on screen,” she says. “I’m still ambitious to do certain things that I still haven’t done.”

At 28, Walter’s life was plenty complex offscreen. Her sister was pregnant, which was when she realised her own periods had stopped. She was subsequently diagnosed with anorexia, though she credits a voracious commitment to work with pulling her through.

What do you remember of your life at 28?

Well, it was actually a turning point. [I was] a really late starter; I was turned down [by] five out of five drama schools the first time I tried when I was 18. And then I went back a year later and I was obviously a bit more mature and a bit more confident, and I got in. And then I spent the first five or even six years of my career doing what I really wanted to do at the time, which was political and community theatre, which meant poor theatre out the back of a van. You did all the props, you did all the costumes, and you earned the box office takings divided by however many there were of you.

What kind of plays were you in at the time?

There weren’t many parts for women [then]. They were plucky little housewives and sentimental dying women. But around 28, I did this wonderful show, which was called The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, about the beginnings of the trade union movement. They decided I should play the apprentice boy. I’d watched boys all my life because I wanted to be a boy when I was a kid. There’s no film record of it, so I can say it was one of my better performances in life. I got an agent out of it and I got my next job, which was doing a film for television written by Ian McEwan about Alan Turing called The Imitation Game. I remember having my 28th birthday [on set] in the canteen with Richard Eyre.

In your book, Other People’s Shoes, you talk about not wanting to be cast as the posh girl, but in Succession, you’re playing a pretty posh English lady. What interested you in that role?

Well, I was right to avoid that early on because I could have easily played posh little girls on the West End stage and I wouldn't have had nearly such an interesting career. And second of all, I did a lot of Shakespeare, [and] it’s not a defining point within Shakespeare. When I finally did get cast as a posh girl in a TV series, I couldn’t remember how posh people spoke. I had to go to my sister and my mother and get my accent back because I’d been all over the place. I also don’t subscribe to the stereotyping of posh people. I have recently played some horrible posh people, but I’ve also played some nice posh people.

What camp do you think Lady Caroline falls into?

She’s damaged, rather than cold and horrible. To me, she grew up as a lonely child in a very frosty, aristocratic country cold house where nobody knew how to show affection. And she was mostly brought up by her nanny, and life was pretty dull. So when she got the chance to run off and get into the drug scene, which she did, and then go to America, I made her a party organizer in New York, and then she meets Logan Roy and she thinks, “Wow, on that kind of money, I can live the way I want to live.” She also has a very, very, very small boredom threshold. She’s not horrible nasty; she’s enjoyable nasty.

And as to the way she treats her children, there was a scene that was cut from the first season where Kendall says to Caroline, “I’ve been seeing a shrink and he says I should say, ‘I forgive you.’ So I want you to know I forgive you.” So that scene [in Season 2] where she doesn’t deal with Kendall’s problems and disappears at breakfast the next day, she’s got a feeling that if Kendall’s going to talk to her, he’s going to be psychoanalyzing their relationship and giving her a hard time about what a bad mother she’s been.

You mention briefly in your book that you were diagnosed with anorexia in your late 20s. If you were to speak to 28-year-old Harriet now, would you recommend therapy to her?

I probably would, though I don’t think anorexia is very easy to understand. I mean, even now I don’t because people say to me, “Can you help my daughter or my granddaughter?” and I can’t really, even now. There are so many things going on. And obviously the person I saw was not a psychologist. The person I saw was a GP who, in those days, there wasn’t [much] knowledge; there wasn’t even a phrase called “eating disorders” as far as I knew. And so his theory was “buck up and eat something.” But I think I was on the brink of wanting to get out of it myself. I’ll tell you what got me out of it is work.

It was the same for me. I remember my dad just being like, “You’re going to have to get on with this.”

I mean, it’s probably unfashionable to say it because I do believe we ought to know ourselves and analyze. We really ought to be honest with ourselves. But at the same time, I’ve found what little counselling I’ve ever done got me rather too obsessed with myself, when actually what I needed to do was to get out and look at the world and get concerned with other people. What stopped me being obsessed was work and the difficulty of keeping up the lie because you have to do a lot of lying, like, “Oh, I’ve eaten already. Thank you.” To do that over several years with a theatre company is quite hard stuff. And in the end, you’re longing for someone to say, “Look, give yourself a break. Have a meal.”

Did you want to be married at 28?

Oh, that’s a good one. I think I’d only been asked to be married once in those times when I was about 20. And I was very in love with him, but I said, “Marriage is a dirty word to me.” I remember saying it just because everyone in my family kept getting divorced, and I just didn’t really believe in the institution. And those words have come back to haunt me because I think... not that particular person, but it is an area of my life that I’m not sure, like, did I want children? Those are all questions that I can’t sit here and absolutely tell you I know the answer to. It was always a bit more problematic than that. And I know they say you’ve got to be honest with yourself. I don’t know how honest I was with myself.

When I was 28, I was in a happy relationship that I’d been in for about four years, and we carried on for another four years, and we are still friends to this day. But I knew I didn’t want to marry and have his children. And that in the end, I ended it. I just wasn’t ready. And then I think what happens to a lot of women is right about the end of my 30s and early 40s, that was if ever [the moment] I was thinking, “Oh God, I really ought to have kids.” Certainly in my late 20s, I was deferring, deferring, deferring.

And my older sister, she got pregnant when I was 28. And it was around then that I went to see the doctor because I wasn’t having periods. And that’s how the whole anorexic thing came out. But it was very much a trigger, “Oh, my sister’s gotten pregnant, and I’m not having periods. Well, how am I ever going to get pregnant?” So that must have been in my brain. But I also think that it worked out the right way for me, that the journey I needed to take was to do a lot of work through acting, work on myself through acting, grow up through acting, and meet all my relationships I’ve had through acting.

That's oddly reassuring to hear as a 33-year-old who is terrified of marriage.

Really? I love young people and I work with them all the time, and I’ve got nephews and nieces, and I get a lot of feed from them. But I’d probably be a terrible mother. I don’t know.

What do you think your 28-year-old self would think of yourself today?

She would not believe what’s happened to my life. I think I would think, “Thank God you’re still doing it. How amazing that you’ve done what you want to do for 45, 50 years.” What else would I think? I would just think I’d still be ambitious to do certain things that I still haven’t done.

What are those ambitions that are still bothering you?

Well, I think I’d love to do something very complex on screen. Obviously if you’re doing a cameo role, you’ve got to be recognizably consistent because in the storytelling: “Oh yes, that’s her.” If you’re playing the central role or one of the more central roles, from scene to scene, you can show the complexity of a human being. And I’m determined to show that we don’t get less complex as we get older.

Was there anyone you knew in your late 20s who’s gone on to have a career that you wanted?

You’re going to laugh, but I came to attention about the same time as Meryl Streep. And so I watch her, not with any rivalry obviously, but just an awareness that circumstances can make things happen. Obviously, she’s a genius, and I’m not going to compare myself to her, but she was a late [bloomer]. She was 30 or something when she hit the news. She’d been doing fantastic theatre work up till then.

And I suppose there’s a bit of jealousy that I thought, [in the U.K.] we didn’t have a film industry in those days. We had a very strong TV culture, and very good writers and technicians and film directors and lighting people were all in TV. And we still have [a film industry] that is very much hanging on the coattails of the American industry. But I think exposing some of the work I’d done on TV, if that had been the size of The Deer Hunter, I could have been Meryl Streep and I could have had three children and been able to afford a nanny. But no two careers are the same, and I’m very lucky to have had the one I've had.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on