28

At 28, Cherry Jones Read The Handmaid’s Tale. Years Later, She’d Star In It.

The novel haunted the actor, even as she was living it up with her “theater mates.”

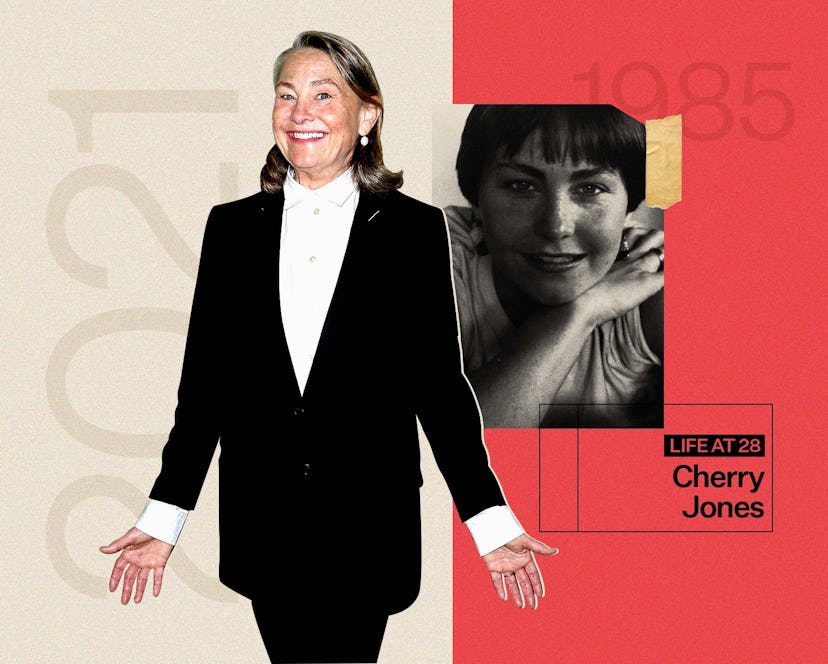

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out most, and what, if anything, they would do differently. This time, Cherry Jones talks about her new film, The Eyes of Tammy Faye, and how the theater world has evolved.

In 1985, a 28-year-old Cherry Jones was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, pondering America’s fall from grace. The up-and-coming actor had picked up a copy of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale as soon as it had been published; spending time near the campus where it was set made the cautionary tale feel all too close. “I would walk past the Harvard wall and just cringe,” Jones tells Bustle of the book’s infamous execution setting. Then she’d turn on the TV and see echoes of the novel’s theocracy in real life: in President Ronald Reagan, who was elected to his second term in office with the help of the Southern strategy and Evangelical enthusiasm. Or in televangelists Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, who were preaching the prosperity gospel directly into congregants’ living rooms.

Decades later, Jones — now a venerated actor of stage and screen with multiple Emmys and Tonys to her name — finds herself revisiting these cultural moments. First, as Offred’s mother in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale, and more recently as Tammy Faye’s mother in the eponymous biopic The Eyes of Tammy Faye. As Jones has carved out a career in the arts, the country has crept closer to Atwood’s dystopia, with ever-stricter controls placed on women’s bodies in the name of God. It’s a progression that has, in all likelihood, been supported by some onetime fans of Tammy Faye’s TV program The PTL Club (PTL for “Praise the Lord”). Did it seem inevitable back then? “It absolutely felt like it could go either way,” the actor says.

Perhaps because the battle lines had yet to be drawn. While Reagan’s communications director, Pat Buchanan, deemed the AIDS/HIV crisis an “an awful retribution against gay men” in a 1983 op-ed, Tammy Faye was advocating for AIDS patients. “No one had a field day with Tammy Faye Bakker’s mascara like gay men,” Jones says. “But at the same time, once they realized what she had done for the community, people became devoted to her.” Heterodoxy: a relic of another time.

Some things, at least, have changed for the better. Jones is relieved to see the days of the “white bastion of theater” waning, replaced by a more diverse and inclusive status quo. Jones was able to marry her wife, filmmaker Sophie Huber, because of laws only recently certified nationwide. (Not that her sexuality was ever an issue in the theater world, which was always “rife with homosexuality.”)

Below, Jones opens up about her life as a 28-year-old, how the theater world has changed, and the advice she’d give her younger self.

Take me back to 1985. How were you feeling about about your life and career?

Oh, I was having a wonderful time. I was doing Love’s Labour’s Lost at the American Repertory Theater [in Cambridge] and a couple of other things, but most of the work I had done there, I did earlier in the ’80s. But I came back and did a few things. Then I was in New York. I had moved into an apartment in Brooklyn with friends, so I was just going between New York and Boston. I had been in a relationship and we had ended amicably. And so I was a single girl again, but just working very hard and enjoying being with my theater mates.

A lot of nights you were on stage, but when you had the chance to go out, what were you doing?

Well, I was always on my bicycle. I had lived in Manhattan and I still felt like going to Brooklyn was a little bit like going to the country. So when I would hang out, I would hang out more in Manhattan, I have to admit. I would just go to theater pubs and places with friends — go and take a bottle of wine and sit outside the Beaumont theater on the steps to Juilliard and just hang on a hot summer’s night. And I’d go to things in the park. The city was getting ready to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Brooklyn Bridge.

It was a sweet time for the city, until AIDS was full bore, and then it was just a nightmare... ’85 was just as everything was turning dark as far as AIDS.

What are you proud of from that time?

I was always pleased that I stayed in the theater world exclusively as long as I did, because I needed to learn more. And I’m a slow learner. So it took me years and years and years before I felt I could hang out my shingle as an actor. In fact, it wasn’t until I was about 33 that I really felt like that I knew what I was doing. So at 28, I still had another five years to go before I could call myself an actor without blushing. So I was proud of myself for sticking with that.

And I was just also very, very, very, very fortunate, because I was doing theater at that time. I was white and almost every theatergoer in America at the main not-for-profit theaters were performing for 98% white audiences. So I benefited tremendously. And that’s hopefully a very antiquated situation now and will never, ever, that cannot happen again. And that’s a glorious thing about the progress in the United States in the last several years. No going back to the white bastion of theater.

What’s it been like to see the industry change over the years?

It’s been a sigh of relief. And I will say that when I graduated from college in 1978, there were 12 of us. And four of us were African American and the other eight were white. And I went into the world of theater knowing that my job was going to be a thousand times easier. And it was. I had a friend — a Black actor — who went straight into A Chorus Line. And then I think another friend went in as a dancer, into the theater world. And then my other two friends became teachers, but it was just hard. I mean, it’s hard for anyone going into theater, but in those days, if you were not what they called “Procter and Gamble,” “P&G,” which meant white and cute, it was going to be very difficult to have a career. And that’s just the way it was.

So when Hamilton came along — I mean, there was a lot that came along before that. And an organization called The Non-Traditional Casting Project was started, I think, in the ’80s ... But they did a tremendous amount of good, of convincing not-for-profits that Romeo did not have to be a white boy and Juliet did not have to be a white girl. And that was sort of the beginning, but it’s taken another 30 years to make a dent.

We’ve spoken about the privileges that you had going into the industry as a white woman. But was it challenging at all to navigate the industry as a gay woman?

You know, in the theater, which is rife with homosexuality, it was not a problem. Had I had a budding film career as a 28-year-old gay woman, that might’ve been quite different. Then I might’ve been encouraged to keep my mouth shut. And I would not have, because I can’t imagine anything worse than not being able to be who you are. I mean, we’ve seen what it does to certain people who hide for years and years; it can’t be easy on their psyche. No. But it was easy-peasy for me.

What advice you would give your 28-year-old self?

As an actor, we can torment ourselves over our shortcomings, as everyone can for one reason or another in this world. And I would just say to try to treat oneself as one would treat a dear friend, with tenderness. I think that would be it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on