Books

The Price Of Prestige At Goldman Sachs

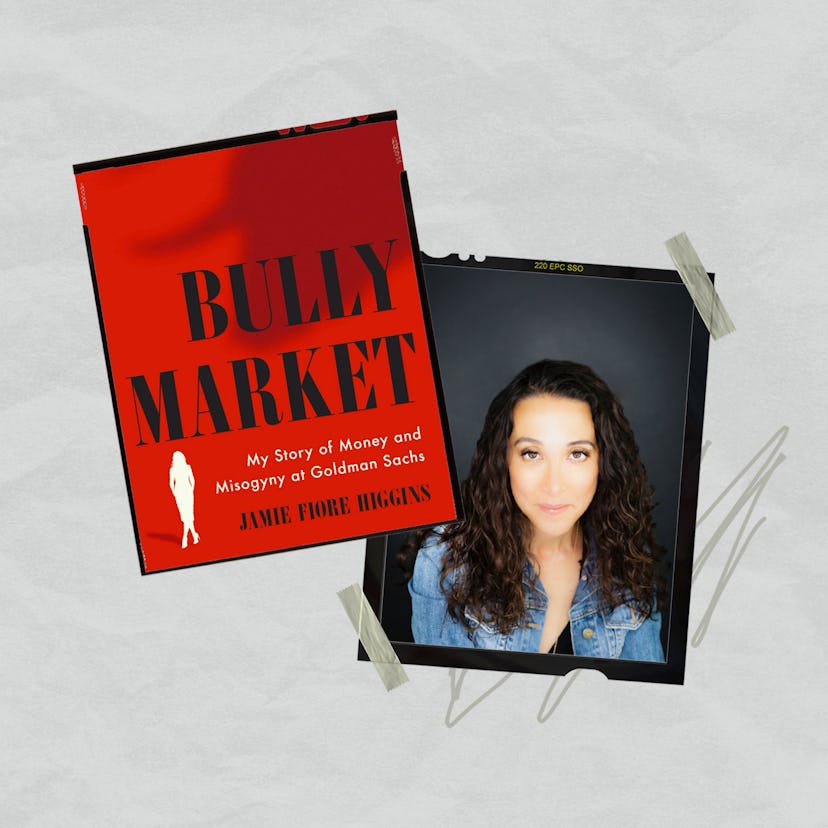

In her gripping new memoir, Jamie Fiore Higgins shares a wildly candid account of her time at the top.

Does a seven-figure paycheck make being demeaned on a daily basis worth it? That’s what Jamie Fiore Higgins wondered over the two decades she worked at Goldman Sachs. Eighteen years after joining the finance industry titan at age 22, in 2016 Higgins quit, leaving equity and stock on the table. She was 40 years years old, making $875,000. The New Jersey native was among the few women who rose to the ranks of managing director, but her professional success came at a cost: an alleged torrent of verbal harassment, a miscarriage in an office bathroom, and a workplace affair that almost destroyed her marriage. Higgins writes about it all in her debut book, Bully Market: My Story of Money and Misogyny at Goldman Sachs.

An alternate take on the “Wolf of Wall Street” trope, Higgins internalized the attitude of her superiors to the degree that she bullied other women when she found herself in a position of power. “I did not want to write this as ‘Oh, Jamie is victim,’” she tells Bustle. “The bigger story was about how this job changed me.”

In a statement to Bustle, a Goldman Sachs spokesperson says, “We strongly disagree with Ms. Higgins’ characterization of Goldman Sachs’ culture and these anonymized allegations. We have a zero tolerance policy for discrimination or retaliation against employees reporting misconduct, and all claims are thoroughly investigated with discretion and sensitivity.”

Below, Higgins talks about her affair, cultish behaviors, and whether she’s personally heard from Goldman.

“My infidelity was an escape, just like Xanax was an escape. It was me being caught in a difficult environment and grasping for anything to give me relief.”

What made you want to write this book?

Where I’m from, right outside of New York, there are a lot of people with big careers in the city. There’s a huge obsession about what you do for work. For the first few months after [I left Goldman Sachs], I was really depressed. I didn’t know who I was, what I was meant to do. My job anchored me to this world.

I threw myself into volunteering at my kids’ schools, which helped. Then #MeToo happened, and that changed everything. As I was consuming #MeToo stories, I saw my own experiences reflected. I started writing this book to help make sense of my experience. Why was I there for so long? Why did someone who had grown up with such strong convictions, who was really cared for as a child, why was I so ripe for the picking? I sit with a lot of regret for what I’ve done. Writing this book is a way to make amends.

What do you think made you “ripe for the picking,” or, in other words, susceptible to the kind of cutthroat environment that Goldman Sachs cultivated?

My whole childhood was overshadowed by medical issues. I had very severe scoliosis. For years, I was in clinical trials and wearing back braces. I eventually had to get a very expensive surgery because my spine had started to compress my heart and lungs, [which] put a huge strain on my parents. When I recovered, I wanted to be the perfect kid.

You write about how you were demeaned and belittled from Day One, how your co-workers called you “Sister Jamie” and made fun of you for not partying as hard as them. Was there anything that a woman could have done to get ahead and be respected?

I do think I was recognized for my work ethic. I was intelligent, I was good with numbers, and I was recognized for that. I was considered “one to watch,” an up-and-comer. But as I went up the chain, it became less about my intelligence and more about my ability to keep my mouth shut and look the other way.

You describe a lot of cultish behavior in the office, like a boss who handed out bananas to you and your team and said, “You’re all monkeys in my book. You’re overpaid, and I could replace you at any second.” Do you consider Goldman a cult?

My joke is that Goldman put the “cult” in culture. I’ve watched that Leah Remini series about Scientology and the Netflix one about Warren Jeffs, and I see themes of unwavering loyalty. There were so many tenets that were repeated: “You’re lucky to have Goldman. People would kill for these jobs.” We were kind of indoctrinated.

And eventually, you became the indoctrinator. What was it like to adopt the language of the higher ups who demeaned you, like when you told an intern to get rid of her nail polish: “This is Goldman Sachs, not a nightclub”?

At the time, I felt I was doing it for her own good. I had heard what people had said about her nail polish behind closed doors. It was a high: I was the one people were stopping to listen to, finally. I reveled in it.

Even when you hated going to work, you kept at it because of the promise of your annual bonus. What was it like to hold a check that started at $80,000 and went exponentially up from there? Did it cancel out the bad parts of the job?

Yeah, and my family spurred me on too. My brother would say, “Jamie, it’s work. It’s not play. They’re not beating you. It’s a lot of money.” The reasoning was it’s not that bad. Once you get that bonus, you forget about everything that bothered you. It’s like childbirth: You go through all that pain and then you have the baby and you’re holding it in your arms and thinking “that couldn’t have been so awful.”

For me, it was never about living large. When I made [managing director], I treated myself to a $100 coat from T.J. Maxx. It was about [having a financial cushion in case] one of my kids has to have spinal surgery. It was about sending them to college.

You write about how you pretty quickly got addicted to the prestige of working at Goldman and then scaling the ranks. That addiction to prestige seems endemic.

The addiction to prestige is everywhere. It’s in the perfectly curated, filtered lives on social media. I had this crazy experience where I looked so great on paper, but I absolutely disintegrated inside.

Can women compete in a boys club? Is it possible?

I don’t see how it was possible in my world at Goldman. I hope these big, powerful organizations can make changes. It’s great that you’re hiring 50% women, but what can you do to retain them? In my heart of hearts, I don’t think anything has changed materially. If you’re passionate about finance, there are a lot of other places to do finance.

Have you heard from Goldman about this book?

I haven’t. I’ve heard from a lot of Goldman women who are still there, in my DMs, on social media, who’ve said, “Thank you for being honest about your affair. Thank you for saying that.” I’m sure it’s going to be shocking for families that know my husband and I personally. But it shows that life is real, and it’s messy and it’s dirty.

Let’s talk about that affair: Did you consider not writing about it?

No, this book couldn’t be one-sided. I did not want to write this as “Oh, Jamie is victim.” I was, but the story is about how this job changed me, how I treated women at work, and how I treated my husband. I changed as a person. My infidelity was an escape, just like Xanax was an escape. It was me being caught in a difficult environment and grasping for anything to give me relief.

Now that you’ve told your story, what’s next?

I want to do anything I can to support the message of this book. I’m also coaching right now — I got trained to be a life coach. I talk to executives, college students, people at all stages of life who are trying to figure themselves out. I get what it’s like to be in the thick of careers, to be managing marriages and children. You get on that hamster wheel of your career, and time just flies. That’s how I got into trouble. I lived and died by what Goldman thought of me from the ages of 21 to 40. It feels really good to be out of that place.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Editor’s Note: This article was updated to include a statement from a Goldman Sachs spokesperson.

This article was originally published on