TV & Movies

Why Our Obsession With Bring It On Endures, 20 Years Later

And what our fascination with cheerleading stories says about us.

“Hate us ‘cause we're beautiful, but we don't like you either... we're cheerleaders!”

Within the first two minutes of Bring It On, the film lets us know that it’s in on the joke. The Toros’ opening cheer is performance art, equal parts self aware and self-criticism. It tells the audience: I know how you might feel about cheerleaders, and frankly, I don’t care.

When the film came out 20 years ago, there was nothing quite like it that centered cheerleading as a competitive sport. Rather than simply use the archetypal cheerleader to paint the picturesque high school experience, Bring It On delved deeper into the politics behind the uniforms, telling a story of cultural appropriation long before Hollywood’s brazen lack of diversity was part of the mainstream conversation.

The image a cheerleader conjures in the American psyche is pretty much always that of a blonde, thin, straight, beautiful young woman who rules the school. Cheerleaders have shown up in one way or another in just about every teen movie of the last 20 years, yet in that time, our understanding of the grueling realities of the sport has changed dramatically (see: docuseries like Cheer). Yet as the world and our conception of the sport changes, Bring It On still endures two decades later. The reasons extend beyond simple nostalgia: Not only is it entertaining, but it dissects the cheerleader archetype, pushing the superficial popular-girl image up against thornier subjects like cultural appropriation and homophobia. Passing off Bring It On as nothing more than fluffy early-2000s girl-power cinema overlooks the power of the movie’s progressive approach to themes of race and class. “We were talking about privilege before we knew that word,” writer Jessica Bendinger tells Bustle.

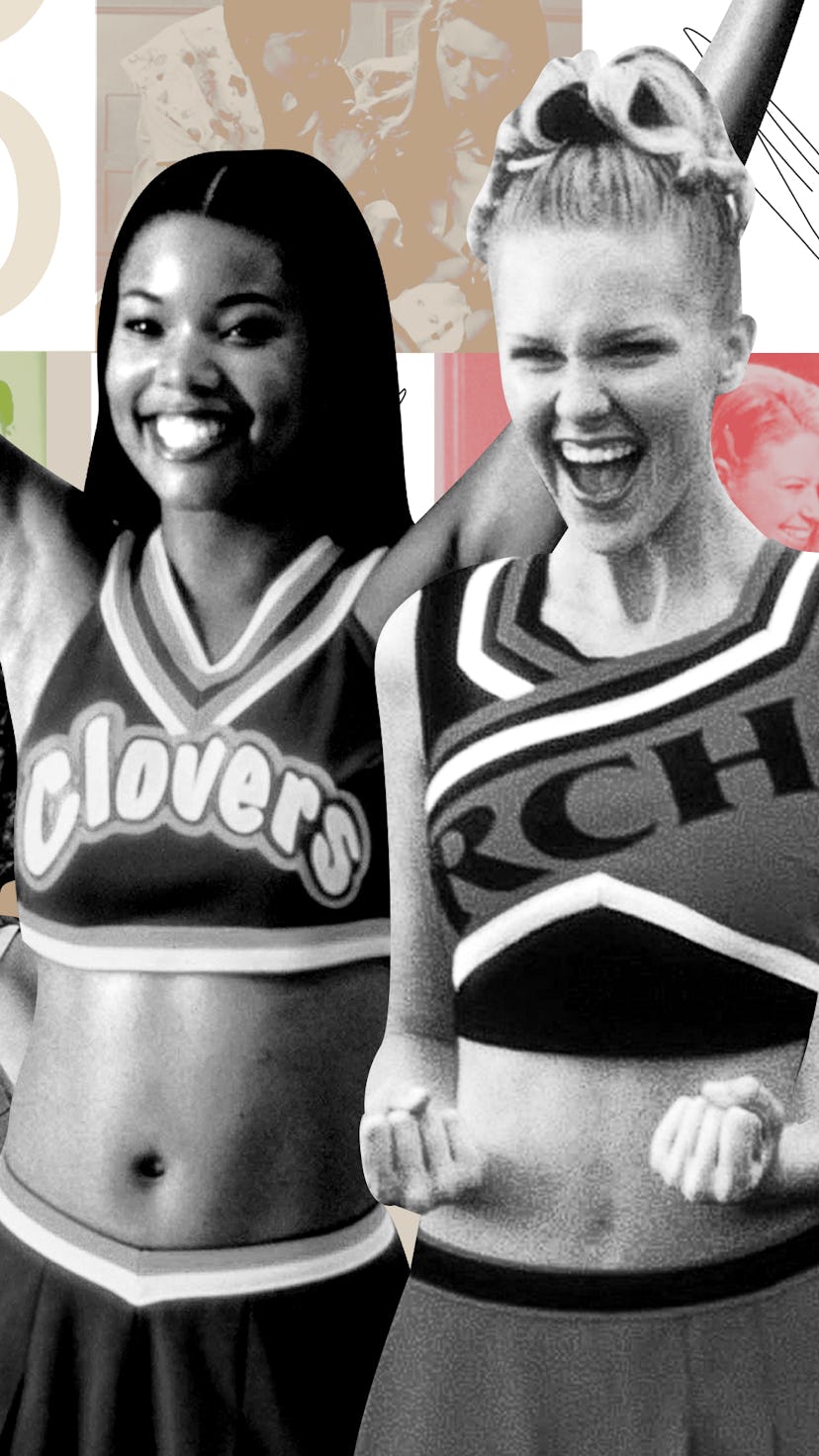

Set at an idyllic San Diego high school where Torrance Shipman (Kirsten Dunst) has finally been promoted to cheer captain, Bring It On’s central tension comes from her realization that the Toros' cheers have been stolen from the East Compton Clovers, a Black cheerleading team from the other side of town. She’s faced with a moral dilemma: continue profiting off labor that was stolen from Black women, or put in the work herself? “I wanted to counter racism in a covert way by being really brassy about it,” Bendinger says. In the end, it’s Isis (Gabrielle Union), the cheer captain of the Clovers, who leads her team to their rightful place as national champions.

The critic Roger Ebert once rightfully referred to Bring It On as the Citizen Kane of cheerleader movies, but it was far from the only movie to examine the cult of cheerleader worship. After a steady stream of sports films in the ‘90s, Bring It On was part of a small burst of cheerleader films around the year 2000 — including But I’m a Cheerleader (1999) and Sugar and Spice (2001) — that interrogated the idea of the cheerleader as the quintessential hometown heroine.

But I’m a Cheerleader came out quietly in 1999 but has since developed a cult following for its darkly humorous portrayal of Megan (Natasha Lyonne), a small-town cheerleader who’s trying to repress her attraction to other women. Megan cannot fathom that she’s gay — isn’t she a cheerleader instead? In the world of the film, queerness and being a cheerleader are mutually exclusive, and the dissonance causes endless confusion for Megan, who acts as an unwitting bystander to these two parts of her identity. She’s dating a football player, for God’s sake!

Sarah Hentges, a Professor of Women’s Studies and American Studies at the University of Maine at Augusta, credits But I’m a Cheerleader’s enduring appeal to the ways the film made fun of and challenged traditional stereotypes of the sport and those who participate in it. “It’s important to really look at what [these characters’] stories add to the larger narrative of cheerleading,” Hentges says of Megan and Bring It On’s Isis. “These characters are othered girls — girls who aren’t normally the center of stories. They are girls of color, girls who are queer, girls who are of a lower socioeconomic status.”

That cheerleading has always been depicted as the domain of beautiful straight white girls is a product of the sport’s roots in American history. What is now a competitive sport was previously a side attraction considered an accessory to the football team. This brand of cheerleading “is considered by most Americans to be a pre-feminist relic and joke,” notes Pamela J. Bettis, co-author of Cheerleader!: An American Icon. Yet interestingly enough, the origins of the sport stretch back to male-only universities in the late 1800s, when big men on campus mustered school spirit using military chants. At this time, cheerleaders were respected. A 1911 editorial in The Nation observed: "The reputation of having been a valiant 'cheer-leader' is one of the most valuable things a boy can take away from college. As a title to promotion in professional or public life, it ranks hardly second to that of having been a quarter-back." Then women started getting involved.

“Once cheerleading became feminized in the years after World War II, cheerleaders began drawing intense vitriol from a range of ostensibly disparate social groups. These include feminists, social conservatives, cultural elites, sports administrators and fans, mainstream media commentators and members of the general public,” says Emma Jane, an Associate Professor of Communication & Media Studies at UNSW Sydney whose work focuses on sex, gender, and the ethics of technology. “That cheerleading attracts such a diverse group of haters has always been extremely fascinating to me.”

Cheerleaders are often fetishized or tossed aside as objects of male desire rather than actual athletes. They are a staple in the porn world, Jane notes, citing the famous adult film Debbie Does Dallas, which depicted a group of high school girls trading sexual favors for money to send one of their teammates to audition for the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. With this sexual interest comes the tension between two conflicting representations of cheerleading in mainstream media and pornographic discourse: “They are either worshipped as highly prized, inaccessible erotic icons or derided as ‘loose’ sluts sexually available to anyone,” Jane says. They are both sexually available or total prudes, effectively drawing ire from everyone. Think Lester Burnham blowing up his suburban life out of lust for high school cheerleader Angela Hayes in American Beauty or Taylor Swift demonizing the cheerleader eyeing her object of affection in her “You Belong With Me” music video. There is no winning. Putting cheerleaders at the center of a story is inherently divisive, even more so when you consider the patriotic tradition behind the sport.

This image of small-town girls wearing tight skirts and dancing on the sidelines at football games has been a powerful force in upholding our obsession with all-American girlhood. Even more insidiously, it perpetuates racist Eurocentric beauty standards and glorifies harmful stereotypes of the real-life athletes who participate in the sport. So it makes sense that in January 2020, the Netflix docuseries Cheer would become a phenomenon for demystifying and undercutting these notions of prototypical cheerleader perfection and glamour both aesthetically and emotionally. The series, which follows members of the Navarro College cheer team as they prepare for the National Cheerleading Championship, depicts the grim realities of the sport, from the the barriers to entry for performers from marginalized groups, to the crushing effects of physical injury, to the limits of what a life in professional cheerleading can actually provide.

Cheer is difficult to watch at times. Bones break and heads hit the floor at startling speeds, but that’s just a part of daily life as a Navarro cheerleader. Coach Monica is ruthless in her leadership, and the squad bends over backwards for her approval in ways that could be considered borderline toxic were it not for the team’s undying love for her. Unlike the poreless smiling faces of the cheerleaders in Bring It On, the sweat and the tears of the Navarro cheerleaders are seen in vivid detail.

So, too, are their stories. Jerry Harris cheered through the loss of his mother and livelihood, La’Darius Marshall cheered his way through his adolescence despite being bullied for his sexual identity, and Lexi Brumback cheered even without the financial means to pay for the sport. Their journeys to the mat were not easy ones, and that’s the point. It’s a feat that Cheer pays homage to cheerleading’s small-town Americana origins while subtly criticizing the closed-mindedness in some depictions of the sport.

Yet even Cheer has a cheerleader-like tendency to smile through or gloss over the pain, leaving true reckonings with issues surrounding race, socioeconomic status, and homophobia not fully explored. In a way, it’s a fitting microcosm of the problems still prevalent in American society. The world of competitive cheerleading can be tumultuous if you’re not straight, rich, and white. But if you replace “competitive cheerleading” with most other professions or past-times, the sentiment still rings true. Perhaps America really is a cheerocracy after all.

This article was originally published on