Books

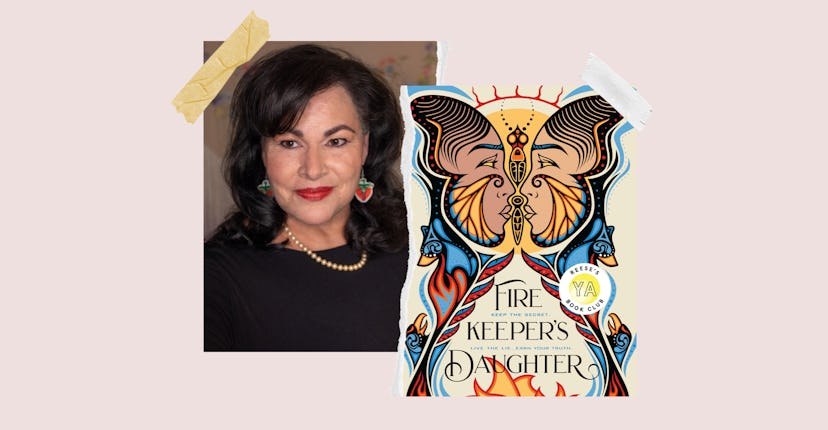

How Angeline Boulley’s Own Young Adulthood Inspired Firekeeper’s Daughter

Everyone from the Reese Witherspoon to the Obamas has fallen for the YA novel.

Plenty of authors have taken their time writing books, but few have a story quite like Angeline Boulley — the powerhouse behind the YA novel that’s set the literary world ablaze. The author first conceived of the idea for Firekeeper’s Daughter as a teenager, but didn’t put pen to paper until she was 44, and another decade would pass before she sold it. By the time Boulley was trying to find a publisher, her book had gone through so many iterations that she feared it no longer fit into a single genre.

Boulley needn’t have worried. Her work went for seven figures at a 12-way auction, and after it hit store shelves this March, Firekeeper’s Daughter became an official selection for Reese’s Witherspoon’s YA book club and a New York Times bestseller. On top of that, Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company Higher Ground has optioned the book for a Netflix series.

Firekeeper’s Daughter tells the story of 18-year-old Daunis Fontaine, a biracial Ojibwe woman who witnesses a gruesome murder and is asked to go undercover to help solve the crime. As if that wasn’t enough, Daunis is also navigating a devastating family tragedy — and trying to understand her feelings for a mysterious new guy.

Below, Boulley talks to Bustle about the true story that inspired the book, the Obamas, and her dream cast for a TV adaptation.

You came up with the idea for this book when you were 18, started it in your mid-40s, and then finished it a decade later. What was that process like? Where did the idea even come from?

The idea came from one of my friends [who] went to a different high school. She told me about a new guy senior year, and that he was just my type. I will say I was intrigued; I was single and intrigued. So I asked about him and it turned out that he wasn't my type. He did not play sports and he hung out with the stoners, so I didn't pursue anything. [Laughs.] And then at the end of the school year, she said there was a huge drug bust — and it turned out that the new guy had been an undercover officer. I remembered thinking, what if I had met him and we liked each other? And then I thought, well, what if it wasn't that he liked me, but that he needed my help? So then that was kind of a question of, well, why would an undercover investigation need the help of some Ojibwe girl? It was always in the back of my mind.

And [in] different jobs that I had after college, I worked in different tribal communities and I saw a lot of my students grappling with identity issues, much like I had. So [I had] the idea of a story that was deeper than a crime thriller; it was more about identity, too. Both ideas just kept swirling around.

What made you decide when you were in your 40s — and you had kids and obviously a lot of other things going on — that this was the time to start writing the book?

Well, mostly it was that my daughter was a preteen — and so I thought, well, by the time I finish this, she'll be in high school and maybe this book [will] help her. And then I had a son who played hockey and I saw how star athletes get treated differently. So all of these different little ideas and pieces about my kids really informed [me] that now was the time to try to write this book.

There've been so many conversations recently about #OwnVoices authors, and bringing these authors into more genres in mainstream publishing. Why do you think it's important that your story is part of the YA genre and told from the perspective of a young person?

It's very much in the YA lane, because the claiming of one's identity and place in the world is very much a YA hallmark. So in the end, that's the category that felt right. But there are versions of the book drafts that I had done where it was adult and other ones where it was maybe even younger, like middle school. [Throughout] 10 years of writing, it's kind of gone through a lot of different iterations. I'm really happy with where I finally got [to], which was at the very upper edge of young adult, and very easily crossing over to adult [fiction].

YA is also a genre generally known for being more progressive and moving at a faster pace in terms of promoting social change than other genres and audiences.

In terms of finding their voice and doing something with it, [young adults] jump first and ask questions later. I think the older I've gotten, the more calculated I become in decisions I make. And there's something that's just so — I don't know if “irrepressible” is the right word — but there's just something so wonderful about teens seeing wrongs in the world and wanting to do or say something about it. And that's [why] I think that YA is further along than other arms of publishing.

The past year has also brought about so many conversations about the lack of diversity in publishing, as well as whose stories get told and how. What were you thinking about in terms of making sure your book very much stayed centered on a young Native woman and didn’t water down her experiences?

I was happily surprised that my publisher did everything that they could to make sure that I was being true to my vision for the book. For example, I had said something about cover art, and as a debut [author], there's a limit to what I can call the shots on, of course. But my agent had negotiated that I'd be able to have input regarding the cover. And so I really appreciated that the publisher found an Ojibwe artist; they knew that it was important to me to have an artist [who] sees things the way I see them, like the beautiful florals and colors. I was so happy with the cover and other things too, like my decision not to do a glossary. My editor [Tiffany Liao] is phenomenal. And I think she understood what I was saying about not having a glossary.

Obviously we need to talk about the Obamas of it all, because it's super exciting that their production company optioned the book. What details can you share about how this opportunity came about, and how you will be involved going forward?

It was right after the book auction, and there was a lot of buzz about [it]. Production companies started reaching out for the film rights or the option. And so I went through kind of a similar process of talking with different production companies, and right from the get-go, I really loved the shared vision that Higher Ground Productions had. So my role is as executive producer and script consultant; I will not be writing for it.

I'm really excited about it. When I wrote [the book], I'm a visual person, so I would play out scenes almost like how it would be onscreen. And then I would write the story, write the scene, the dialogue. So I think my writing evokes that real visual imagery of the story and the senses.

I was glad that they wanted it for a series instead of a film, because I think that with a film, you have to figure out — it’s a 500-page book — what you have to reduce that to a 90-page script. The beauty of a series and something that they felt strongly about was they loved all the quirky characters and the elders. And by doing it as a series, it gives more opportunity to tell other stories of these characters that people fall in love with.

You're not necessarily the person casting your own series, but is there anyone who would be on your dream cast list?

With writing the story over 10 years, a lot of the actors that I initially thought of for parts are aged out. For example, my original Jamie was Bob Morley who plays Bellamy Blake on The 100. But now I like Joel Oulette, and he starred in the Trickster series. I'm not sure if I like him for Jamie or for Levi. I love Forrest Goodluck, and I think of him as Stormy. Booboo Stewart as Travis. Devery Jacobs as Lily. And then I just started watching Resident Alien. The actress [who] plays Jay, I think her name is Kaylayla [Raine]. I just got into it over the weekend, and I said, I think that that could be Daunis!

Your initial deal for Firekeeper's Daughter was part of a two-book deal. What are you working on in terms of that next project?

[Book two] is an Indigenous Lara Croft, but instead of raiding tombs, the main character is taking back ancestral remains and cultural items from museums to bring them back home, and then one of the heists goes very badly. So I'm working on that, and that's one of the reasons why I didn't have any interest in writing the script. I really want to focus on what my lane is, which is telling these layered mysteries that have deeper [meanings].

I'm just so excited beyond belief at the way [Firekeeper's Daughter] is being received. And I love when I get messages on my social media, particularly from Native women who say [they're] from a different tribe, but letting me know that they felt seen in a story.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This article was originally published on