TV & Movies

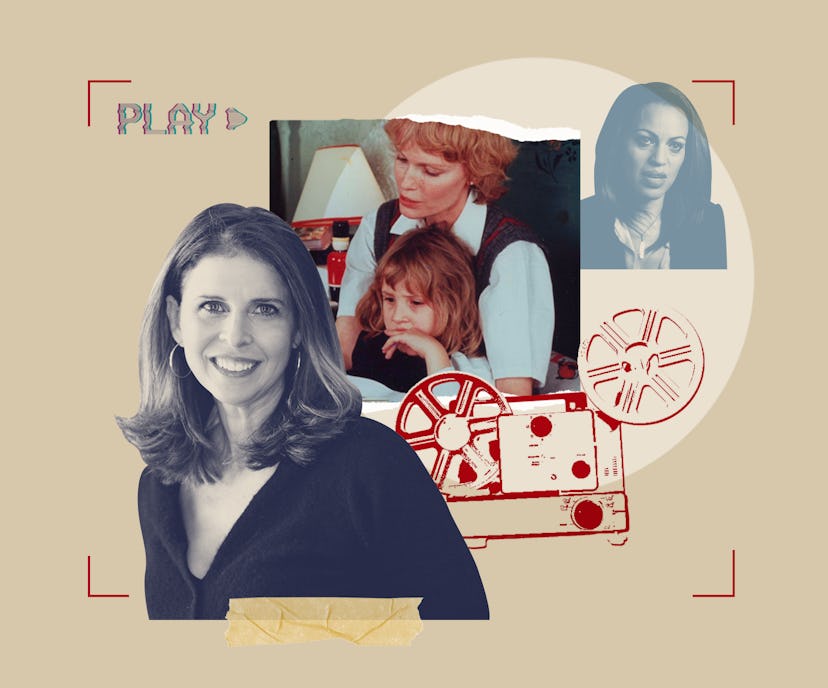

#MeToo’s Preeminent Documentarian Is Just Getting Started

From Allen v. Farrow to On The Record, Amy Ziering has been behind some of the last decade’s most important films about sexual assault.

When Amy Ziering was 15, she returned home from school to find a document that would unwittingly change her life. Left on her bed was a play her father had written about his experience in concentration camps during the Holocaust. It was something he never spoke about; Ziering was mystified. “I went to him and I had a lot of questions. I said, ‘Why didn't you ever talk with us about it?’” the filmmaker recalls over Zoom from Los Angeles. “He said, ‘You know, when I came out of the camps as a kid, I tried to tell people about what had happened and people either didn't believe me or it was just too much for them. So I just buried it.’”

In the ensuing decades, Ziering, 59, has spent her career making space for the silenced where her father was not afforded it. Her first film, 1998’s Taylor’s Campaign, turned an empathetic lens to a Santa Monica man experiencing homelessness; 2018’s The Bleeding Edge exposed the harm wrought by the for-profit medical device industry on its patients. Over the last 10 years, she and her longtime collaborator Kirby Dick have distinguished themselves as the preeminent #MeToo documentarians, castigating the figures and institutional forces that have allowed rape culture to flourish without consequence. They upbraided the Pentagon in 2012’s The Invisible War, their Emmy-winning exposé about rape in the U.S. military, and assailed college administrations in 2015’s The Hunting Ground. More recently, they flew in the face of Hollywood, examining the allegations of sexual abuse against music mogul Russell Simmons in 2020’s On the Record and director Woody Allen in HBO’s 2021 miniseries Allen v. Farrow.

The impact of their work has been profuse. The Invisible War led to sweeping policy change, five congressional hearings, and the passing of over 35 pieces of legislation; The Hunting Ground incited the introduction of three bills in U.S. Congress and 28 in state legislatures; On the Record opened the conversation about sexual assault to Black survivors long left out of it; and Allen v. Farrow spurred a nearly 20% increase in calls per week to RAINN, America’s largest anti-sexual violence organization. Their projects have together catalyzed national discussion and been hailed as historical touchstones, but Ziering and Dick’s aim is ultimately less immediate or measurable: in bringing understanding to issues like sexual assault and systemic power, they hope to shift cultural mores. “We're seeing it sort of in the wake of #MeToo,” Ziering says. “If there are consequences for these kinds of actions, a lot less people will get hurt.”

“These ideologies were so part and parcel to our way of being, we couldn't even recognize them as toxic. It was like the air. You don't notice the air.”

Ziering and Dick’s films are grounded in fact, but most effective is their ability to breathe life into these stories, illuminating the intimate and personal ways each subject has been affected by trauma. Dick credits this to Ziering, who conducts nearly all of their interviews. “She has a very caring way of interacting with subjects, allowing them to open up and share their most painful and difficult experiences... in a way that makes them feel safe and heard,” he says. During the making of Invisible War, one woman revealed that in the two decades since she was raped, Ziering was the first person who believed her; another drove three hours to an Ohio screening of the movie so she could tell Ziering that watching it finally allowed her to stop blaming herself.

Being an advocate is instinctive for Ziering, who began reading seminal feminist theory during her sophomore year at Amherst College. Her parents, both active philanthropists, had politicized her early on: her mother brought her along to campaign for Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern and later California gubernatorial nominee Tom Bradley; her father took in an Iranian refugee and assisted Russian immigrants during her childhood in Beverly Hills. “That was just sort of his way of being. And it taught me that that’s what you do with your life and how you live,” Ziering remembers of her dad.

Still, Ziering’s films have been as educational to her as they have been for her audience. She admits she was under-informed about sexual assault until Invisible War, which she says she “went into naively.” She was driven to make the film after reading a Salon article in the mid-aughts “about some women who were assaulted and had no access to an impartial system of justice.” It made her nuts. “I was like, ‘I don't even get it. Like what do you mean? There's just nothing to do?’”

With Mia Farrow especially, she says it was initially hard not to buy into the prevailing narrative that — scorned by her partner of 12 years leaving her for her much younger adopted daughter — Farrow had coached her other daughter Dylan into fabricating sexual abuse claims about Allen. But later — and certainly after making Allen v. Farrow — that idea became unfathomable to Ziering. “In the ‘90s, I believe that I did not have the sophistication or education to interpret what I was hearing about Mia Farrow appropriately. I did not have the tools. And when I was thinking about that, I [realized] I couldn't have [had the tools] at that age,” she says. “These ideologies were so part and parcel to our way of being, we couldn't even recognize them as toxic. It was like the air. You don't notice the air.”

“Everyone said, 'No one wants to hear women's stories. No one wants to hear stories about women being raped. And no one certainly wants to hear stories about women raped in the military.’”

Ziering’s films have the odd distinction of straddling both sides of the #MeToo movement, beginning not long after Tarana Burke coined the hashtag in 2006 and stretching through its proliferation in 2017. Within that span, Ziering has seen attitudes transform in real time. When she and Dick pitched Invisible War in 2010, they couldn’t find anyone to fund it. “Everyone said, 'No one wants to hear women's stories. No one wants to hear stories about women being raped. And no one certainly wants to hear stories about women raped in the military.’” But after #MeToo gained momentum, Ziering’s cell phone exploded.

On the Record and Allen v. Farrow both came out of that time period. Working on them simultaneously wore on Ziering, who developed secondary PTSD while producing Invisible War but eventually learned how to care for herself while enveloped in others’ trauma. “I think with [Allen v. Farrow], having finished it in isolation... I’ve kind of been retriggered,” she says. If anything, though, it’s only cemented the importance of her work. “If this can do this to me, I'm fine. I'm OK. I don't have a referential trauma to reflect back on. Like, just imagine someone who does and what all their loved ones who have to live in that aura of trauma are going through.”

In other ways, too, the last year has emboldened her. “I remember with Invisible War having to remind myself to smile when I’d go on TV, or [I’d be coached], 'Don't be so angry when you talk about sexual assault,'” Ziering says. “[But] recently I've become much less self-censored and I think that is post-Trump. If that guy could get up and say the most racist, sexist, disgusting, and vile things and [70 million] people still [voted for him], it's like, I've got no f*cks left to give. I’m going to say whatever I want.”

She’s going to show it too.

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, you can call the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit online.rainn.org.

This article was originally published on